The cruise industry has set its sights on becoming carbon-free ... one day.

Cruise lines are more likely to come under public pressure to clean up the fuel they burn than other shipping segments, and they took an early lead, fitting scrubbers to wash out the noxious exhaust gases that passengers might breath.

But they have been quiet since then compared with the main container lines and bigger bulk carriers.

Carnival Corp, the world’s largest passengership owner, says it has lowered its carbon footprint by 25% by putting scrubbers on more than 70 vessels.

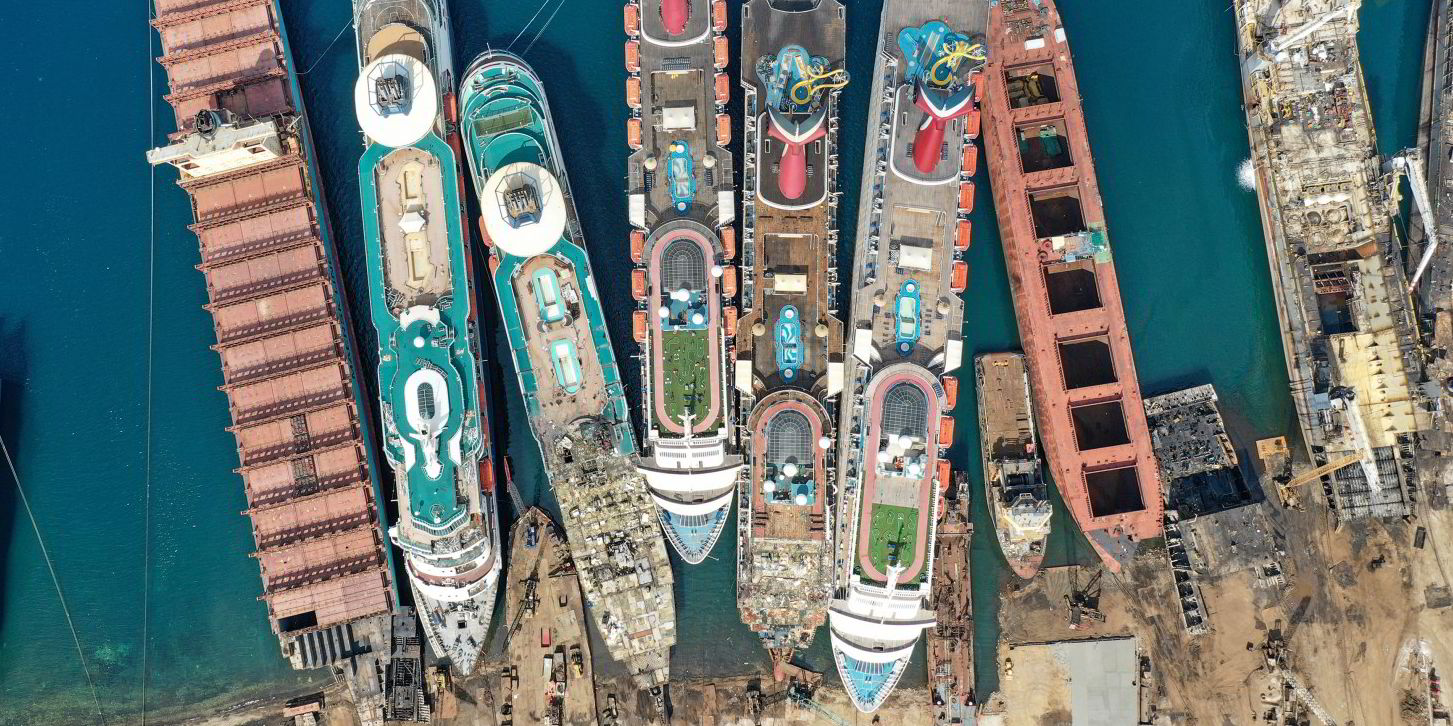

It also reduced its fleet size to 87 ships by removing the 15 most inefficient vessels last year during the Covid-19 shutdown.

Carnival plans to eliminate four more ships this year and have 11 LNG-powered vessels in a few years as part of its goal to lower emissions by 40% by 2030. “We also have a broad partnership with Shell on supply of LNG,” spokesman Roger Frizzell says.

“We are piloting new green technologies such as fuel cells and large storage battery systems, but we plan to continue to explore new developing technologies as part of our strategy going forward. Everything is on the table as these new technologies emerge.”

Carnival has set these ambitious decarbonisation goals while paying millions of dollars in fines for environmental malfeasance over several years.

Since then, it has appointed a chief compliance officer and joined the Getting to Zero Coalition, a group of 140 organisations aiming to at least halve shipping’s 2008 greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The coalition is working to introduce zero-emission ships into the global fleet by 2030.

Royal Caribbean Group and Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings, which cover 80% of the cruise market with Carnival, have scrubbers on most of their vessels.

“As for the future, Icon class, the next class of ships for Royal Caribbean International, will run on LNG, and we have been seriously exploring fuel cells for a number of years,” spokeswoman Janet Diaz says.

The cruise lines have been vocal about their use of scrubbers to lower carbon output but are tighter-lipped on alternative fuels beyond LNG, batteries and fuel cells. The rest of maritime, meanwhile, has talked about exploring biodiesel, methanol, ammonia and wind.

Data analytics

In 2014, the International Maritime Organization included passengerships within its Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) that requires all ships to be built to much higher efficiency standards by 2030. Phase-four EEDI standards being drawn up by the IMO may include a low-carbon fuel requirement.

The Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), which counts 95% of the world’s passengership owners as members, is trying to help the industry reach a zero-carbon future. In 2018, the association committed to pushing its members to reduce carbon emissions by 40% by 2030 as a first step to becoming carbon-free by the end of the century.

It talks about its members optimising energy efficiency through conservation and energy management, using ecological, slick hull paint coatings, more bulbous bow designs to reduce fuel usage, LED lighting, tinted windows, lightweight steel and solar panels.

The CLIA is also studying the use of ammonia, fuel cells and electric motors combined with batteries.

“The cruise industry has been performing data analytics for itineraries to maximise fuel efficiency,” it says. “Findings in this field have led to reductions in fuel consumption through optimised speed, routes and distances travelled.”

Cruise lines are also using shoreside electricity (SSE) — cold ironing — to turn off ships’ engines while in port, with the goal of eliminating emissions in port altogether.

So far, 68 cruiseships have been equipped to use shoreside power.

Cold ironing has lowered annual carbon emissions at, for example, the US port of Charleston, South Carolina, by 36% and could reduce emissions by 800,000 tonnes per year across Europe.

The primary bottleneck for SSE remains the availability of high-wattage power sources and infrastructure at ports. Only 14 ports out of 800 visited worldwide by CLIA members have the ability to provide SSE: on the east and west coasts of North America, Hamburg in Germany, Kristiansand in Norway and Shanghai in China.

There is other movement on the horizon. In 2019, US fuel-cell developer Bloom Energy partnered Samsung Heavy Industries to develop vessels that can generate some of their power requirements with solid oxide fuel-cell technology that could potentially power and propel cruiseships.

However, experts say the technology’s ability to propel even medium-size passengerships is still at least 15 years away.

Other fuel-cell manufacturers — Plug Power in the US and Germany’s Robert Bosch — are currently focused on land-based uses. Bosch is also looking at shoreside installations in Germany, but is still in an “early pilot phase”.