The decision by a De Beers-backed company to build the world’s largest seabed mining ship has shone a new spotlight on a nascent industry that mixes excitement with controversy.

It is not so much the thought of De Beers' diamonds that are putting a sparkle in the eyes of many global investors, but a potential haul of commodities that are used in smartphones, electric cars and windfarms.

Under the oceans that cover more than half of the world’s surface, rare earth metals are lying in abundance, according to the US Geological Survey.

New rules

And the International Seabed Authority (ISA), set up by the United Nations, is meeting in Jamaica in early July to formulate new rules for this kind of mining to progress faster.

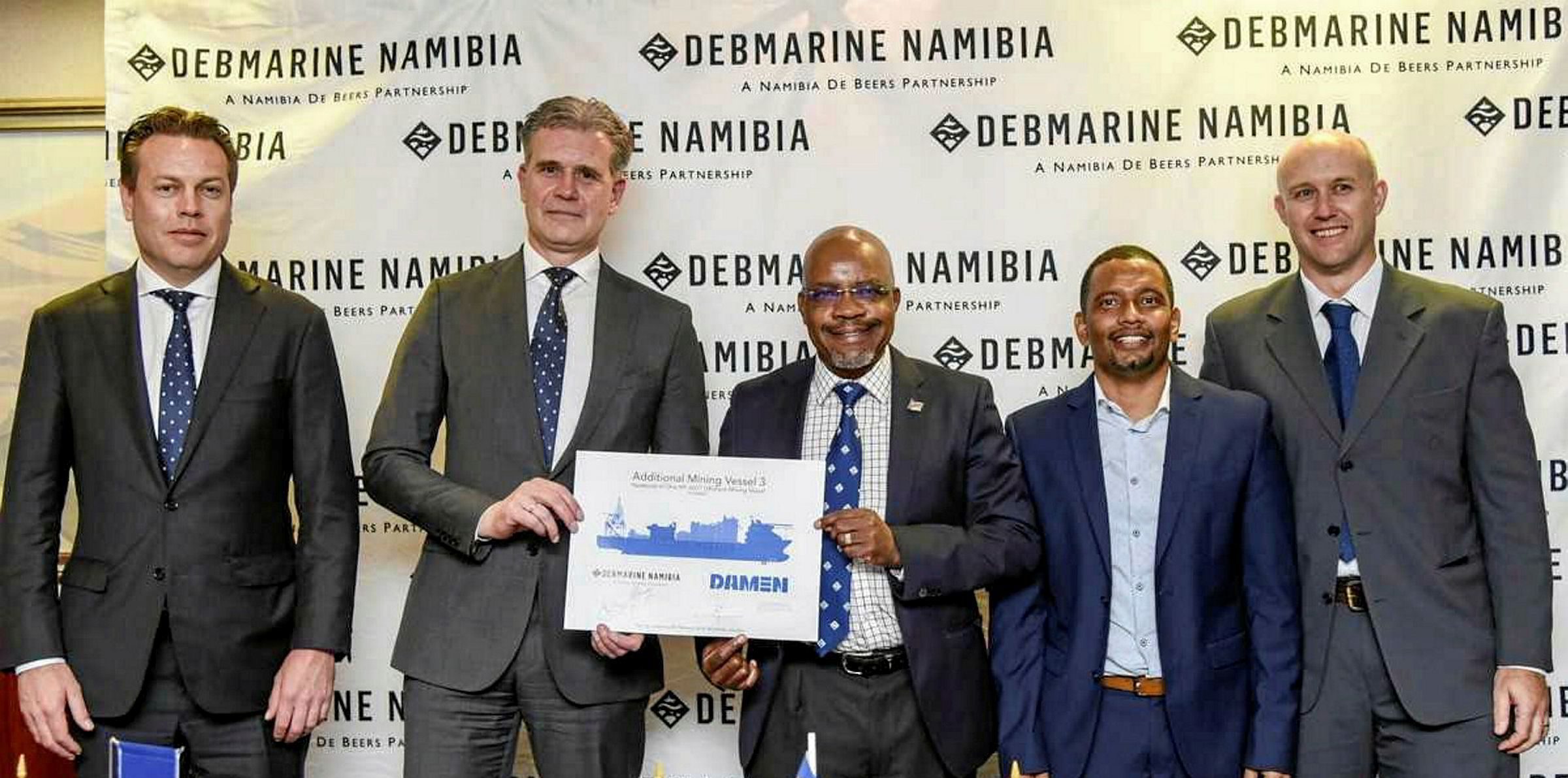

De Beers' $468m order for a 177-metre-long vessel, scheduled to be delivered in 2022 from Damen Shipyards in the Netherlands, signals confidence.

The latest “crawler diamond recovery” vessel will enable De Beers and its 50% Namibian government partner to increase their output by 35%.

De Beers has actually been at this marine activity alongside its better-known land mining operations in South Africa since 1971.

It formed DebMarine Namibia 17 years ago and has steadily accumulated a seven-ship fleet, including a $142m unit ordered in November 2017 for delivery from Kleven Verft in Norway in 24 months' time.

Marine mining can be relatively expensive but also avoids some of the human safety dangers of onshore mining.

It can also be free from the problems of “blood diamonds”, where the onshore industry is tarnished by being active in areas overseen by warlords during civil conflicts in places such as Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The concentration of metals within one location is said by one research study off New Guinea to be 10 times higher at sea than on land

Another advantage is that the concentration of metals within a single location is said by one research study carried out off New Guinea to be 10 times higher at sea than on land.

Shallow seas

De Beers, owned by mining giant Anglo American, is operating in relatively shallow seas off Namibia.

The wider interest now is in deeper oceans outside of national territorial waters and that is where the new rules are needed.

Cobalt nodules and rare earth minerals are believed to be most prolific in the Pacific Ocean at depths of up to 7,000 metres.

Unsurprisingly, China, which is the world’s largest importer of minerals and metals, is deeply interested in these prospects.

There is already a state-sponsored China Minmetals Corp that has obtained exploration licences.

Japan, Germany, Russia and India are also all keen to see the ISA make progress on rules to allow them to legitimately work outside of national territorial waters.

Almost 30 exploration contracts of 15 years covering areas of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans have already been handed out.

The authority believes up to 15% of global future copper and nickel demand could eventually be met from the seabed.

The ISA hopes to have a new set of regulations finalised by 2020. Would there be an immediate marine-based mining activity explosion then?

A big determinant will be what happens to the price of commodities, which currently remains in the doldrums.

While many are keen to talk up the massive potential demand for commodities and rare earth minerals, others say better recycling and landside activity can meet all the likely growth.

Unfulfilled ambitions

And the truth is that despite significant hype about the seabed mining sector in the past, those dreams have failed to turn into dollars.

The high pressure, low temperatures and darkness make it technically challenging as well as costly.

The now-stalled Solwara 1 gold, copper and silver mining seabed project off Papua New Guinea was meant to be a successful industry prototype.

But the Canadian-based operator, Nautilus Minerals, had just lost its Toronto stock-listing and been forced to obtain protection from bankruptcy.

Nautilus Minerals has run into a string of problems, not helped when a mining ship order went sour and Anglo American sold its stake in the business.

Despite this, others remain upbeat, including Glencore-backed DeepGreen Metals as it works to develop a seabed mining project in the East Pacific with Danish shipowner AP Moller-Mearsk.

But in the background growls the environmental movement, which says the world’s oceans are already under stress from climate change.

They insist the potential impact on biodiversity from seabed mining must be better understood before the ISA triggers any deepsea gold rush.