A recent meeting of an International Maritime Organization made significant progress on building consensus towards medium-term measures to tackle shipping’s carbon emissions.

But in regulations focused on the short-term horizon, it’s what IMO delegates did not do that stands out.

Malaysia, Panama and three leading shipping groups had urged the United Nations shipping regulator to make exceptions in upcoming Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) regulation to ensure shipowners are not penalised for factors traditionally seen as outside of their control, particularly weather and port congestion.

But IMO delegates said the working group rejected making the exemptions, at least for now, in order to use a key Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting in June to move forward guidelines on implementing the CII.

While there are still opportunities to adjust the rules before “soft” enforcement ends in 2025, shipowners groups are worried that low CII ratings will still have an impact in the private sector, in the eyes of charterers and financiers, for example.

“Even just in terms of trying to meet the objectives of decarbonisation, the real danger is market distortion, whereby ships which are less efficient are actually getting a higher rating than ships [that are] more efficient that, simply because of their operational conditions, end up with a poorer rating,” International Chamber of Shipping deputy secretary-general Simon Bennett told Green Seas.

The CII is one of two measures next year in the first major rules on carbon that affect vessels that are currently on the water.

Same EEXI score, different CII scores

Under the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI), identical ships will be treated the same. With the CII, a vessel’s operational profile makes a significant impact on its score.

And that worries shipowners, because the decisions of a charterer or port waiting times will affect the CII grade that a ship receives.

For an example of how this plays out, look to nine virtually identical MR product tankers in the fleet of US-based Overseas Shipholding Group (OSG).

The vessels have the same cargo capacity, engine design, and propeller and hull form, leading to very similar EEXI scores. But when OSG calculated 2023 CII scores for the vessels based on data from 2020, they earned a wide array of scores, ranging from a B to the lowest possible score of E.

“The variance has nothing to do with their design and everything to do with the individual trades they are in and their respective commercial requirements which affect the average length of their voyages and the amount of time they are required to wait,” chief executive Samuel Norton and coauthors wrote in a paper for the Blue Sky Maritime Coalition.

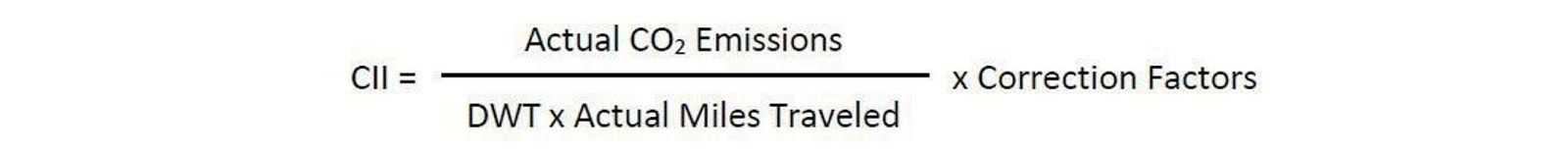

CII can be boiled down to an equation that determines how much CO2 is emitted per tonne-mile, based on vessel capacity rather than weight of cargo carried.

In OSG’s analysis, the vessel identified only as Tanker 9 received a B grade, even though it was among the oldest of the sisterships, all of which operate in the US domestic market protected by the Jones Act.

The main reason for its high score is the long voyages of its regular run between Texas and Philadelphia.

“Long voyages are highly favourable in the CII calculation,” the OSG authors wrote.

Tanker 1 received an E, primarily because it was in the Jones Act spot market, where it was idle for more than half the year waiting for work. When ships are at anchor or in port, because no miles are travelled, it has a way of slamming the CII score.

Rethinking needed?

“A rethinking of the CII is needed,” Norton and his team wrote.

But for proponents of CII, the new regulation pushes the various stakeholders in shipping to work together to solve problems like wait times.

Tristan Smith, a reader in shipping and energy at University College London’s UCL Energy Institute, said keeping exemptions out of the regulation leaves it to stakeholders to work together to optimise a vessel’s operations

“It’s creating the incentive to do that. And I think sector desperately needs it, because so much is written on 100-year-old practice that isn’t fit for energy efficiency,” Smith told Green Seas.

More news on sustainability and the business of the ocean

- IMO consensus for mid-term decarbonisation regulation is building around a basket of technical rules and carbon pricing mechanisms. Click here to read the story.

- Trading giant Trafigura and big data analytics firm Palantir Technologies have joined forces to create a platform that will allow calculation and reporting of carbon emissions across commodities’ supply chain. Click here to read the story.

- A carbon levy would have an impact on the price of delivering cargo, but it would stay within the bounds of normal price swings, according to ICS-commissioned analysis by Clarksons Research. Click here to read the story.