European Parliament president Roberta Metsola recently stood before reporters to talk about a legislative achievement.

Lawmakers had approved parts of the Fit for 55 package of laws and regulations that have been working their way through the European Union’s main institutions aimed at slashing greenhouse gas emissions across multiple industries.

“We can all be proud,” she said. “Today’s vote was really historic.”

With that vote in the rearview mirror, shipping will have to shift from wait-and-see mode to getting ready for what is effectively a tax on greenhouse gas emissions.

That is because part of what was approved involves folding shipping into the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), starting in 2024.

Under the law, shipping companies will have to buy carbon credits known as allowances for their emissions on voyages within the EU, but also voyages between the 27-nation bloc and other parts of the world.

As TradeWinds has reported, parliamentary approval brought plaudits from the shipping industry. In addition to bringing certainty after years of legislative process, the emissions trading scheme will funnel some of the revenue back into projects to support shipping’s decarbonisation. Also, it will enshrine the polluter pays principle, meaning the commercial operators who decide how ships trade will be required to foot the bill.

And the vote drew positive reactions from environmental groups. Faig Abbasov, programme director for shipping policy at Transport & Environment, pointed out that in addition to the emissions trading approval, the European Parliament also reached a March agreement with the European Commission on the FuelEU Maritime law.

That legislation is aimed at requiring emissions reductions and promoting green fuels, while the emissions trading law aims to push shipping to become more efficient.

‘Might not do the trick’

“Whether it will incentivise efficiency that we’re talking about remains to be seen, because there are so many other factors that will be at play. Increasing carbon costs might not do the trick,” he told the Green Seas podcast.

What will shipping have to do to prepare for EU emissions trading?

James Ash, head of the environmental markets desk at shipbroker Simpson Spence Young, said the biggest step that shipping companies need to take to prepare is to work out their route to the carbon allowance market.

On one route, they can start trading on the futures market. On the other, to buy allowances for voyages to, from and within the EU, shipping companies will have to set up accounts with registries in EU member states to hand in their carbon credits, he said.

‘As soon as you can’

“I’ve been speaking to various registries, and it’s going take one to three months to actually set a registry account up. So my advice would be to get a registry account set up as soon as you can, so you’re ready for January 1st in 2024,” Ash said.

One of the factors shipping will have to consider is pricing.

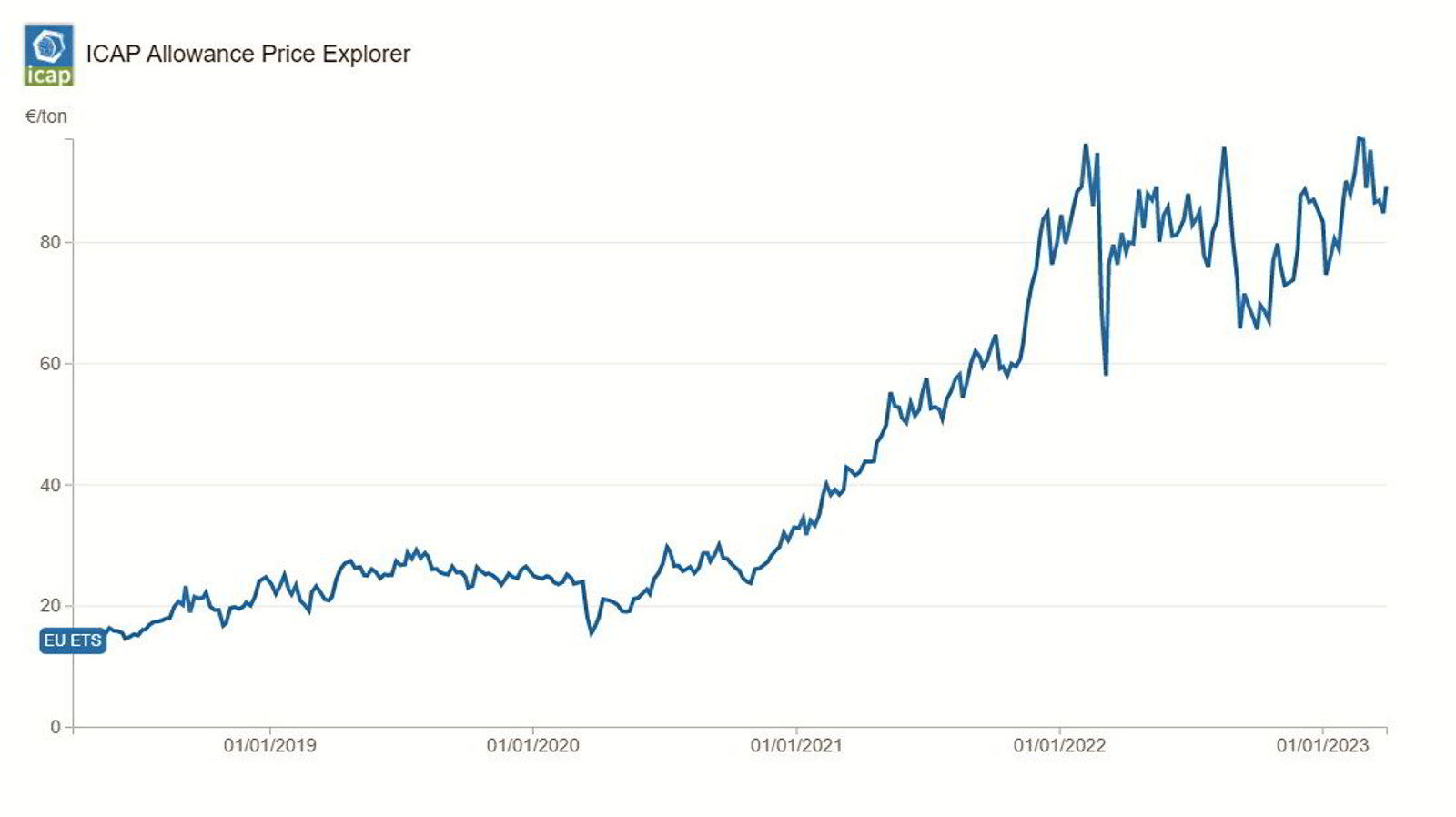

Carbon allowance prices have swung wildly in the last year, topping €100 ($110) per tonne of CO2 in some instances and sinking as far €65.

But in general, prices been on an upward trajectory, from as low as €13 five years ago.

Moving higher

That upward momentum appears likely to continue, partly because over time the number of carbon allowances available in the market reduces.

Ash said it is a supply-and-demand-driven market with many factors, including new EU policies implemented since 2018 as well as the latest vote on emissions trading.

“There are only a certain amount of allowances within the system. So the idea behind it is that you’re adding new entrants to the market … [and] as of 2026 you are going to start reducing the amount of free allowances they give to certain installations in Europe,” Ash said.

“So you’re reducing the amount [of carbon credits] that’s within the system, but you’re increasing the amount of entrants who need to be coming to market who are polluting so [they] need to buy the permits to pollute.”

Piece of the puzzle

And, he said, shipping is a small piece of the EU emissions trading puzzle, so it will largely be the demand from bigger industries like power that drive the price fluctuations, as well as policy from Brussels.

How is a shipping company to navigate those pricing dynamics?

The European Emissions Trading System (ETS) was set up in 2005, but shipping will enter in 2024 after the European Parliament approved revisions in a directive on 18 April.

• Vessels over 5,000 gt that call at EU ports will be subject to the law at the start. The minimum size drops down to 400 gt in January 2025. The addition of smaller ships brought praise from climate tech industry participants who say these vessels can more readily adopt zero-carbon kit.

• For those ships that are covered starting next year, companies must buy allowances 40% of emissions in 2024, 70% the following year and 100% in 2026. Ships travelling to or from outside the EU will get a 50% discount.

• The shipping company named on a vessel’s document of compliance is responsible for administering compliance, even though its commercial operator is ultimately on the hook for paying the cost of emissions allowances.

• Those companies will have to buy allowances not just for carbon dioxide but also for methane and nitrous oxide. Including methane emissions will impact ships that use LNG as a fuel, while charging for nitrous oxide will impact future vessels that run on ammonia.

Some will stick to purchasing carbon allowances on the spot market, some will hedge their positions and some will trade on the futures market.

For Ash, waiting until carbon allowances must be submitted to the EU in 2025 may not be the best route for shipping companies to take.

“I think it’s prudent to purchase your allowances as you go rather than wait to the end of the compliance period, because who knows? As we start in January ’24, we could be trading at €85 a tonne,” he said. “Come a year later, when they look to surrender their allowances as we come towards the end of the compliance period, we could be trading at €120 a tonne.”

Lawyer Nick Walker, a partner at law firm Watson Farley & Williams, said he will be watching for guidance from the EU on how shipping companies will have to register with member states.

He said there does not appear to be anything stopping a shipping company based in one country from setting up an account for their carbon credits with any EU country they choose.

“So it does throw up, particularly … alongside the fact that member states will be keeping the majority of the revenues, whether there will now be kind of venue shopping in terms of where people choose to comply,” he said.

And he said it is not clear that the various countries’ registries will be set up for the kind of regular carbon credit purchasing that Ash suggested.

Walker said that what shipping companies need to be doing now to prepare is reviewing their contracts to take into account the new EU rules.

The directive allows the member state registries to recover costs from ship operators, a fee that will be in addition to the cost of buying carbon allowances in the market.

He said there is a risk of litigation in shipping, particularly given that the shipowner or manager that has to register the allowances may be different from the commercial operator that has to pay for them.

One uncertainty in the law, Walker said, is that the law takes the form of a “directive” that is interpreted by member states rather than a regulation whose interpretation is led by Brussels.

And the risk with directives, he said, is that enforced or implemented evenly around the EU, there could be higher standards in some countries than in others.

Directive vs regulation

“Most environmental regulation coming out of the EU in recent years has been done by regulation rather than by directive. And the reason for that is that they’re usually very contentious. And what commissioners tend to find is that directives aren’t very evenly transposed by member states,” he said.

“And therefore, they have to start infraction proceedings against individual member states, which kind of delays or waters down the impact of the environmental regulation.”

So Walker, who added that enforcement is also up to member states, said he will be watching to see whether some member countries have higher standards than others.

That raises more questions about whether there will be venue shopping.

But Transport & Environment’s Abbasov is not worried about the risk of uneven enforcement, because he said the rules are centralised. There are heavy penalties for shipping companies that do not comply, in addition to having to pay for allowances that they failed to hand over in the following year.

“Basically, they’re getting a double whammy,” he said.

A ship can be arrested after repeated non-compliance with the emissions trading law, as can another compliant ship in the same company’s fleet.

“So the enforcement system is fairly stringent,” Abbasov said.

Ultimately, Transport and Environment sees the FuelEU Maritime legislation as a more powerful tool to reduce shipping’s climate impact than emissions trading. That is because it creates fuel standards that provide clear rules for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The emissions trading system may have an impact in cutting carbon, but its impact is indirect and the cost of carbon credits may not bridge the gap with costlier green fuels.

‘Impactful’ green fuels law

“FuelEU Maritime is impactful because there’s a command and control mechanism,” Abbasov said.

“The media and, in general, policymakers tend to ignore command and control mechanisms and always like talking about taxes, emissions charges and so on. But in reality, the most successful climate regulations have been the command and control mechanisms.”

The EU’s latest moves on shipping emissions are throwing a gauntlet down for the International Maritime Organization.

In July, the United Nations body is scheduled to decide on a new decarbonisation trajectory, with most nations calling for zero emissions or net zero by 2050. And the IMO hopes to make progress on its own fuel standard and putting a price on greenhouse gas emissions.

While many in shipping would like to see a global system and the European measures have review mechanisms built in, Abbasov does not believe any eventual measures by the IMO will persuade the EU to back down. The IMO and EU regulations will likely apply at the same time, he said.

In part, that is because the IMO is unlikely to adopt a carbon price that is high enough for the EU to pull back its carbon allowance requirement. And then there is the revenue.

“Parts of the EU shipping ETS money has already been spent. Member states recovering from Covid-19 borrowed money at the EU level, and that money has to be paid back,” he said.

And part of the emissions trading revenue has already been ring-fenced to pay back those debts, Abbasov said. The EU will be unlikely to give up that new source of revenue.

Port air quality boost

Plus, he said FuelEU Maritime has consequences for air quality in European ports and provides investments in green hydrogen-based fuels in the region.

Now that these legislative initiatives are drawing to a close, Abbasov said Transport & Environment would like to see an EU energy efficiency mandate for shipping, which has been proposed in the European Parliament.

He said that is because if emissions trading leads to efficiency gains, it will only be known after the fact, and because amid the transition to expensive green fuels, the industry should be encouraged to boost efficiency to use less of those fuels.

And the non-governmental organisation wants to see the EU adopt and improve on the IMO’s Carbon Intensity Indicator, which grades ships based on their emissions per tonne of cargo carried and distance travelled.

“You can imagine a world where Europe says, ‘Only the A-rated ships are allowed to call on my ports’,” he said.

That would mean that only the most efficient ships and companies would be allowed to trade in Europe, he said.

Read more

- Green Seas: IMO grapples with plastics pollution from ships’ paint, fishing gear and ‘mermaid tears’

- The IMO would be reckless to ignore the full life cycle of fuels

- Podcast: Should LNG stay on the alternative fuels menu for shipping?

- Token power: Insetting allows shipping companies to take emissions cuts beyond customer base

- Will the IMO make history by electing its first woman secretary general?