In general, things are going well for operators of vehicle carriers. The ships that carry cars and trucks from their manufacturers to their markets have been commanding record freight rates.

Even though economic clouds have softened the automobile market, vessel capacity remains tight, with few orders at shipyards threatening to bring new car carriers into the market.

But since the start of this year, there has been one major problem: congestion at ports in Australia caused in part by efforts to prevent a pest with an unpleasant sounding name from entering the country.

Norway-based car carrier operator Wallenius Wilhelmsen, which has a major presence in the Oceania market, was particularly hard hit.

Although it was still the company’s third-best quarter for earnings on record, TradeWinds reported that its shipping volumes slid 3% and revenue fell from $1bn in the fourth quarter of last year to $956m in the first three months of 2023 — a decline that was partly a result of efforts to keep the brown marmorated stink bug out of Australia.

Insects were not the only problem.

Lasse Kristoffersen, the chief executive of Wallenius Wilhelmsen, said on a company webcast that congestion in Australia was caused by stricter enforcement of biosecurity measures that were also aimed at halting the introduction of invasive seeds.

“Ten percent of the Australian economy, and growing, is agriculture. They are protecting that as well as they can. And that’s why we have for a long time done fumigation of stink bugs, basically small animals,” he said. “But now also they’re focusing in on the seeds, and cars are coming in with seeds. They should have been cleaned before they came on board or vessels.”

Wallenius Wilhelmsen was not alone.

Keeping pests out

The car carrier business has been gummed up by these biosecurity measures in the Pacific as vehicles wait to be rid of pests that Australia is aiming to keep out of its borders.

One of those is the brown marmorated stink bug. The insects pose a danger to agriculture as they consume crops. So far, Australia has kept the invasive species from getting a foothold, and the federal government wants to keep it that way.

The bugs have a way of hitching a ride on vehicles, particularly between September and April, as do the invasive seeds.

Andreas Enger, chief executive of car carrier operator Hoegh Autoliners, said in an earnings webcast that Australia and Oceania represent one of the company’s largest trades.

‘Quite awful’

“It has been, I would say, quite awful during the quarter,” he said of the Australia delays, noting that he travelled to the country to seek solutions.

“It is a huge challenge. We are waiting more than a week per port call in Australia.”

Enger said the situation impacts both the company and its customers, and Hoegh Autoliners is struggling to find solutions.

He said congestion is down in other parts of the world, but many of the company’s return trades include calls in Australia, so the delays impact those routes and take capacity out of Asia.

But stink bugs and seeds are a seasonal problem.

“So we can hope that it will ease a little bit in the summer season,” Enger said.

Wallenius Wilhelmsen’s Kristoffersen also travelled to Australia to witness the problems for himself.

He said cleaning vehicles to make sure they do not carry invasive species to Australia is the responsibility of the manufacturers in the countries that export cars, but that was not happening.

So the operator set up a cleaning operation at the Australian port of Melbourne.

Kristoffersen shared photos of it with shareholders and analysts during the earnings webcast, showing crews with flashlights and what he sarcastically called a “high-tech” device made out of a stick with double-sided tape at one end to pick up every seed off each car.

‘Big backlog’

“This is why suddenly there was a big backlog of vessels in congestion and a big backlog of cars that were not cleared for the market,” he said.

“When I was there in I think in March, we had a backlog of 7,000 cars just sitting there waiting to be cleaned. Now that is down to around 1,000.So in our view, the Oceania issue is now under control.”

He said the congestion is already significantly lower in the second quarter, and the situation should normalise by the summer.

But why is Australia trying so hard to keep the likes of stink bugs and seeds from entering its borders, at the risk of snarling vessel traffic at its ports?

$25bn annual cost

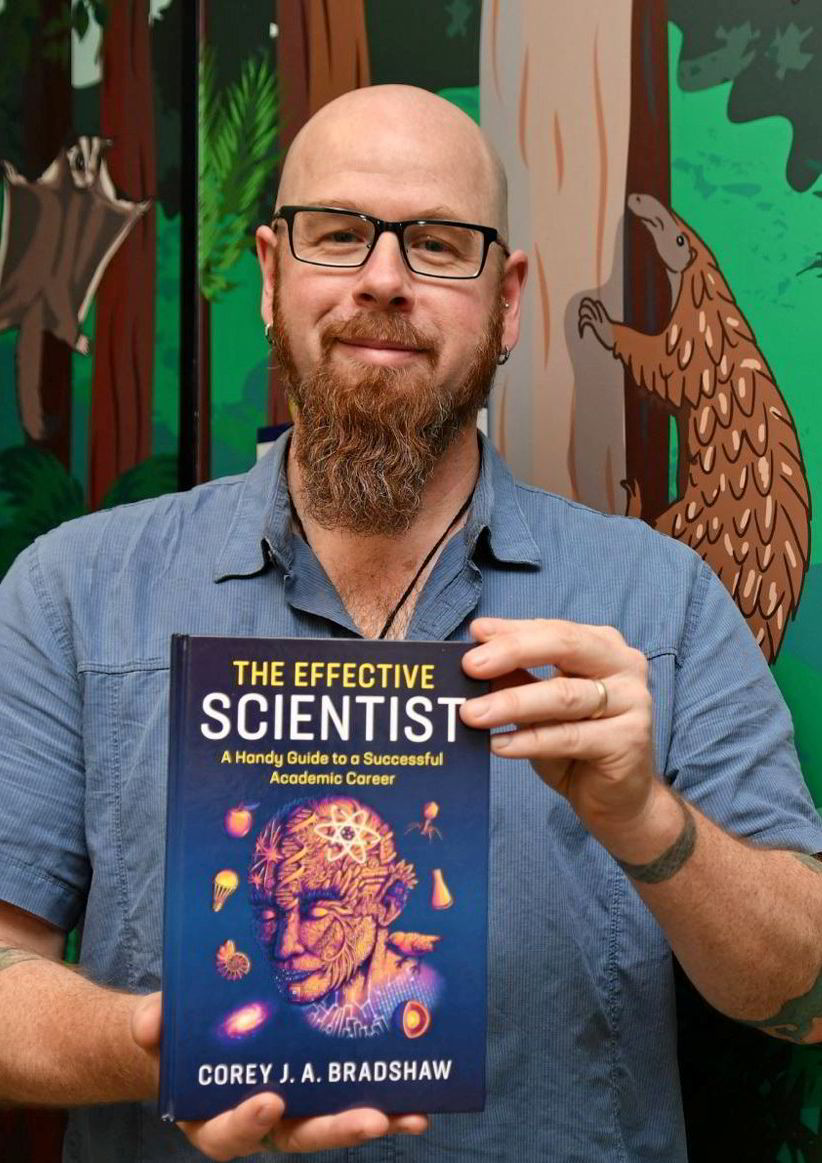

Corey Bradshaw, a professor of global ecology at Flinders University in Adelaide, has calculated that invasive species cost the Australian economy nearly $25bn per year.

That includes the cost of direct damage, like rats eating grain in silos, or spending on biosecurity. It also involves the cost of culling invasive species, like weed eradication, or a project that Bradshaw is involved in shooting deer from helicopters.

The professor said invasive species are a problem around the world, Australia has special challenges.

For one, it is an island continent, so its own plants and animals have evolved on their own without developing defences from, for example, predators like the estimated 25m feral house cats.

“They cause immense damage here much more than elsewhere, because none of our species evolved with a cat-like predator,” he said.

“We’re quite susceptible to these … invasive alien species because once they get a foothold, then they can really take off and exploit the system that doesn’t have … the evolutionary toolkit to deal with them.”

Also, Australia is far away from pretty much everywhere else, and it is connected to the rest of the world by shipping.

Bradshaw said that distance means there is a lot of opportunity for species to hitch a ride to Australia, and only the hardiest species survive the trip.

“So by that, we’re selecting for the most invasive kinds of species just by virtue of the fact that we’re far away,” the professor said.

Past failures

He also pointed to Australia’s failures with plants and animals that are either invasive or were introduced.

Cane toads, for example, were brought to Australia to deal with a problem of cane beetles, but the toads could not jump high enough to get to the insects. They did not do what was intended and caused other damage instead.

Brown marmorated stink bugs are native to East Asia but have migrated to the US, Canada and Europe, where they are a threat to crops.

Products entering Australia, New Zealand, Papeete and Noumea must undergo heat treatment or fumigation from September to April to prevent the insect from impacting ecoystems and agriculture.

Wallenius Wilhelmsen has established an inspection facility at the Melbourne International RoRo & Automotive Terminal to treat contaminated cargo “from dump trucks, boats and cranes to Ferris wheels and supercars”.

The company also has treatment facilities in Baltimore in the US and Zeebrugge in Belgium.

“We’re quite sensitive to what an invasive species can do, because it’s really in our face,” Bradshaw said.

“And because we’re a high-income nation, we also have the resources to be able to assess the damage.”

Keen on biosecurity

The professor said all those factors make Australia very keen on biosecurity, and that has led to successes. There is no foot and mouth disease in the nation’s cattle, and the country has no rabies.

“We’re very keen to keep those kinds of things out, because we know what kind of damage they can inflict and what it will cost us,” he said.

Is putting so much emphasis on biosecurity worth the economic costs of, for example, delaying cargoes?

Crunching large amounts of data on invasive species is one of Bradshaw’s specialities, and he has been involved in a collaboration with researchers around the world who built a database called InvaCost to track the costs. The initiative has been calculating the costs and benefits of investing in invasive species management.

Prevention better than the cure

“As it turns out, in wealthier nations like Australia, that high investment in management actually reduces our long-term costs quite substantially,” he said.

The data showed that investing early in management led to lower costs in the long run.

He said governments can try to deal with the problem later, but the chance of eradicating invasive species once they have become established is very low.

“The damages sort of blossom. I would even say its a nuclear bomb kind of mushrooming effect,” Bradshaw said. “Good biosecurity right up front, while inconvenient, is going to cost everyone a lot less in the long run.”

But one weakness that Bradshaw sees in the current biosecurity system is that the measures are primarily taken in importing countries.

Kristoffersen’s contention that it is up to automobile manufacturers to deal with stink bugs and seeds before cars are loaded on ships resonated with the professor.

He said there is not a lot of biosecurity at loading ports in countries that are the source of invasive species, and while some species die off on a voyage, a lot of them persist.

“And those are the usually the nasty ones,” he said. “Cleaning up the mess at the end is very inefficient.”

Read more

- Green Seas: A (partly) averted oil spill disaster highlights risk of ‘shadow’ tanker fleet

- Wilson Sons cuts greenhouse gas emissions as gender balance improves

- Green Seas: How companies are tackling an ocean-size gap in data about the sea

- Editor’s Selection: Maersk’s profits plunge, Iran’s latest ship grab and what’s bugging Wallenius?

- Green Seas: A US judge mulls court’s say over seafarer rights in pollution probes against ships