Greek shipowner George Economou’s journey through US public markets via flagship vehicle DryShips appears near an end after 14 years, leaving a legacy that, overall, is viewed as punitive to shipping.

DryShips was the company that burst open the door of the New York initial public offering market for a new sector of listed bulker owners in 2005.

At times, it delivered outsized returns to investors, even briefly becoming the largest US-listed shipowner by market capitalisation.

But it also left a trail of corporate-governance complaints, shareholder lawsuits, US Securities and Exchange Commission subpoenas, massive equity-value destruction and, ultimately, the perception that it benefited few but Economou himself.

Sweetened deal

DryShips’ public life neared an end this week when Economou sweetened a deal to buy out the remaining 17% of DryShips' shares not already under his control.

The offer of $5.25 per share is 31% more than Economou’s original bid of $4, and values the full company at $456m. DryShips' shares jumped a corresponding amount to approximately the new valuation, as is usual in such cases.

VesselsValue places a current worth of $454m on the fleet. That does not include a capesize newbuilding valued at about $52m and DryShips’ 100% stake in Connecticut pools operator Heidmar, which is worth an estimated $34m.

But the VesselsValue total also does not include nine bulkers financed through sale-and-leaseback transactions that are worth a combined $321m.

That takes the gross fleet valuation to $861m, and puts the net asset value (NAV) at about $674m.

This suggests Economou is paying about 67% of NAV for the fleet — a discount only marginally greater than where peer dry bulk owners are currently trading.

Jefferies analyst Randy Giveans told TradeWinds this week that the six bulker companies under his coverage are trading at an average 74% of NAV this week.

These include Diana Shipping, Genco Shipping & Trading, Navios Maritime Partners, Star Bulk Carriers, Safe Bulkers and Scorpio Bulkers.

Barring potential resistance from remaining shareholders in the form of litigation, the acquisition is expected to close in the fourth quarter.

Many in the New York financial community and within shipowning peers will not be unhappy to see DryShips go private.

Paying a price

“DryShips was impossible to analyse for years and, unfortunately, is the poster child for corporate-governance failures that make it difficult for the whole industry to operate efficiently in the capital markets,” Deutsche Bank equity analyst Amit Mehrotra said this week.

“It may be hard to see, but the whole industry has paid and continues to pay a price. It comes in the form of steep discounts to net asset values and little interest from the world’s institutional investors."

DryShips has ranked dead last of more than 50 listed owners in the “corporate governance scorecard” introduced by former Wells Fargo Securities analyst Michael Webber in every edition since the rating began in April 2016.

“To be sure, it’s not just DryShips,” Mehrotra said. “It’s others in the industry as well that very unfortunately cast a shadow on those that are good fiduciaries like Euronav, Ardmore Shipping, Eagle Bulk [Shipping] and Star Bulk, among others.”

DryShips was impossible to analyse for years and, unfortunately, is the poster child for corporate-governance failures that make it difficult for the whole industry to operate efficiently in the capital markets

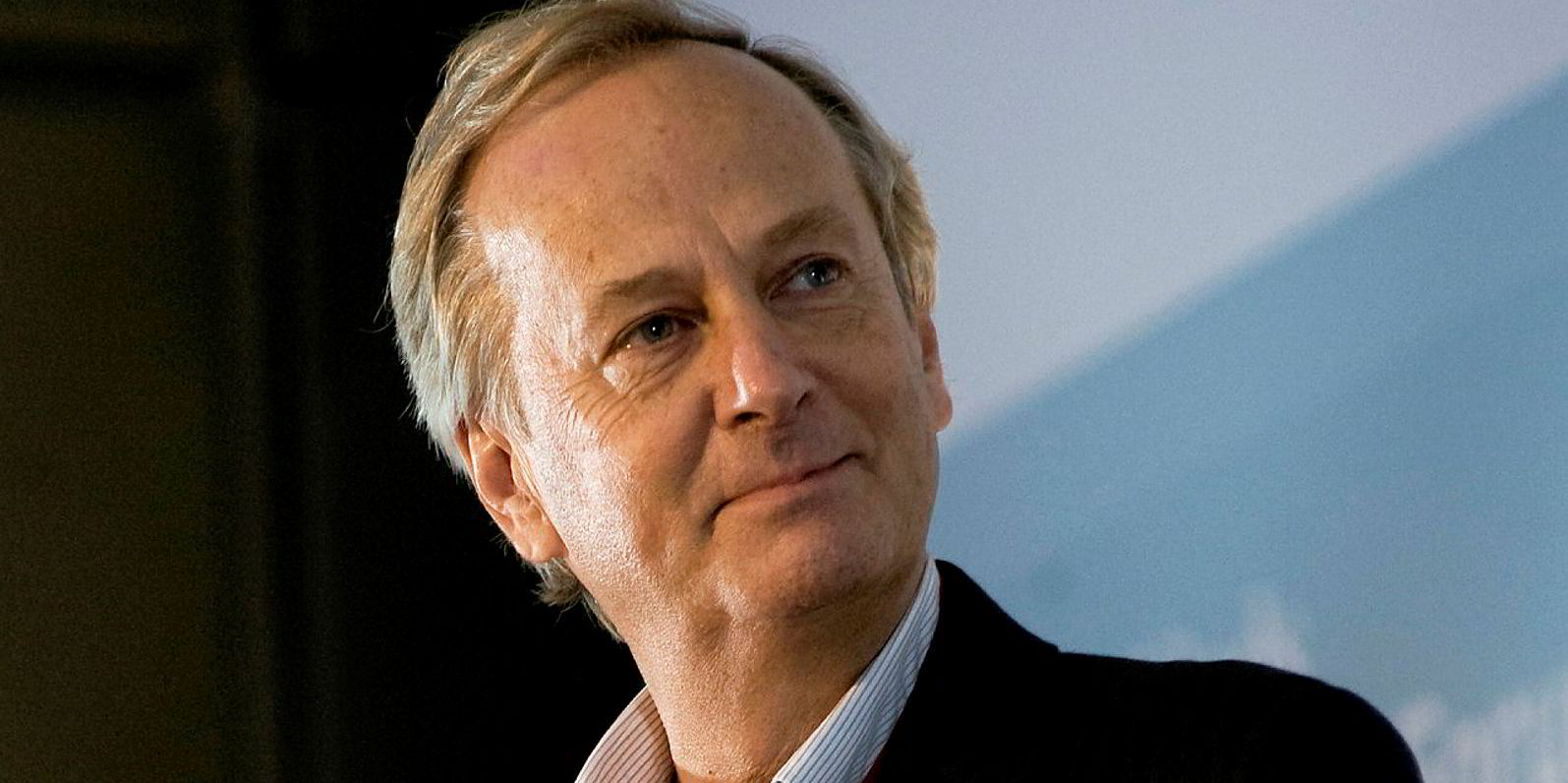

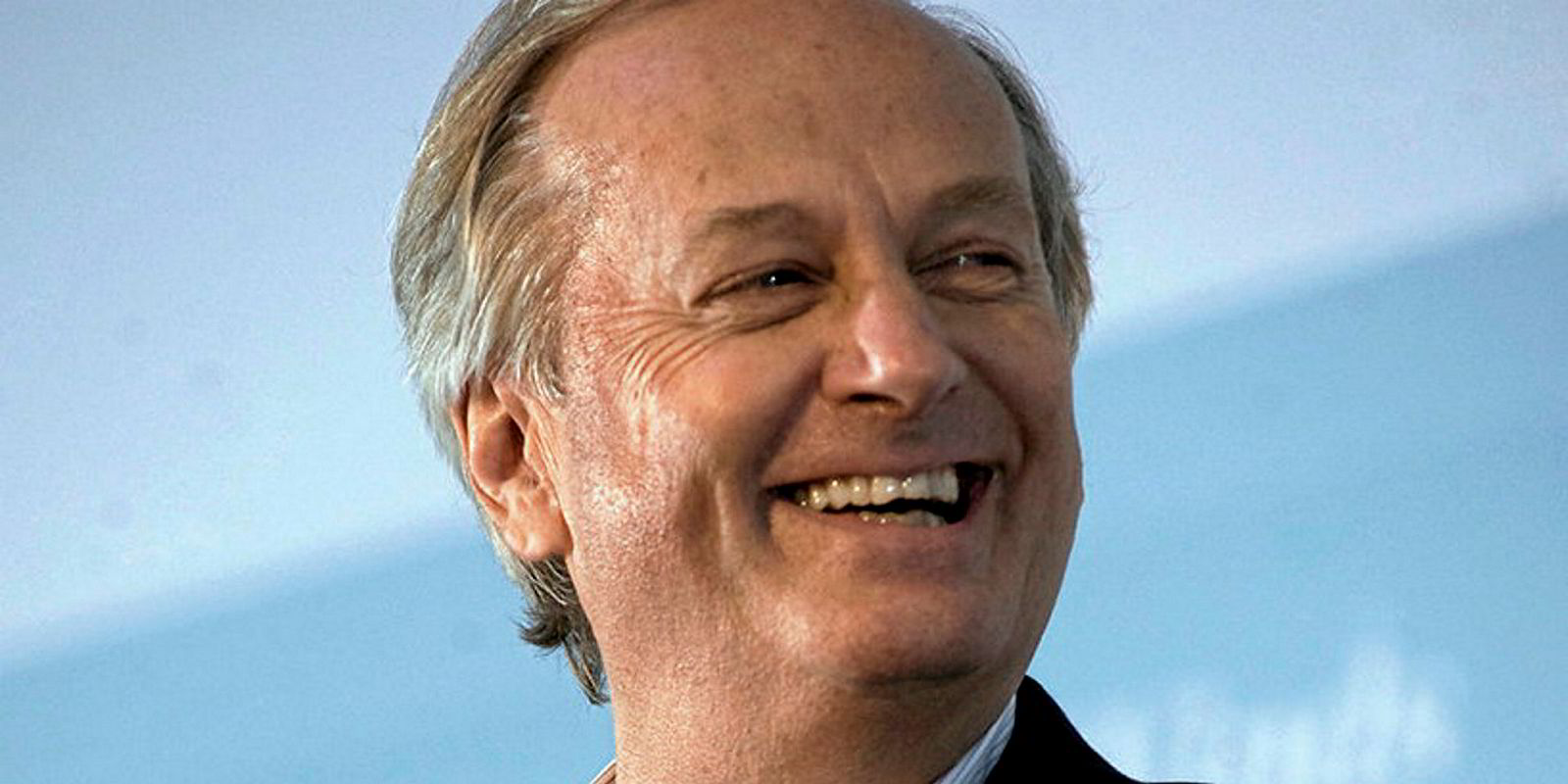

Amit Mehrotra, equity analyst at Deutsche Bank

One executive of a New York-listed shipowner sounded a similar theme.

Shipping landmark

“DryShips’ legacy is that it put an evil taste in investors’ mouths to such a degree that all these other dry bulk shipping companies are trading at 70% of NAV. Some of that is DryShips’ fault,” he said.

A DryShips representative declined to comment.

If DryShips had become essentially blacklisted by the US investment community in recent years — no equity analysts currently cover the owner — it did not start out that way.

Its IPO on the Nasdaq exchange in February 2005 was a shipping landmark in many ways.

It raised nearly double the intended amount of money. Demand was such that underwriters took the unusual step of re-filing the prospectus to capitalise on the windfall. Some estimates had DryShips pricing 50% higher than its NAV at the time.

"I had never seen such demand for a shipping offering," said Anthony Argyropoulos, the Cantor Fitzgerald banker who led the deal, in a 2008 interview.

Right deal, right time

"It was new. People didn't have exposure to dry bulk shipping. People wanted China plays to invest in. It was the right deal at the right time and George knew how to sell it."

What followed in 2005 is now well documented. A record 11 international owners sold IPOs at market, raising $2.6bn. Seven of them were Greek.

"My phone wouldn't stop ringing," Argyropoulos said. "I used to have to chase these people and now they were calling me begging me to do their IPO.”

DryShips proceeded to have its downs — shares dropped 30% by the end of 2005 — and some very notable ups.

A sustained boom in the dry bulk market rocketed its stock to $131 per share in September 2007.

During this period, it briefly became the largest New York-listed stock by market capitalisation, surpassing venerable giants such as Overseas Shipholding Group and Frontline. Nobody traded more shares than DryShips.

Trouble begins

But the global financial crisis took its toll and, by September 2014, DryShips had lost 88% from its $18 IPO pricing.

Two years later, DryShips began a relationship with a financial firm called Kalani Investments that, according to allegations in a pending US shareholder lawsuit, caused it to lose 99.9% of its shares' values while raising $700m between June 2016 and August 2017.

DryShips has denied allegations of shareholder fraud, saying it disclosed all elements of equity sales and subsequent reverse stock splits in public securities filings. It has demanded that the lawsuit be dismissed for lack of merit.

A parallel action against fellow Greek owner Top Ships over its relationship with Kalani was dismissed by a federal judge in New York earlier this month for lack of evidence and what the court found was Top Ships’ extensive disclosure of all dealings.

Both DryShips and Top Ships continue to cooperate with US Securities and Exchange Commission subpoenas over the Kalani dealings, according to recent public filings.

DryShips has tended to prevail in previous shareholder actions brought against it.

And, indeed, it has extensively disclosed a raft of related-party issues ever since its initial IPO prospectus, warning that it might favour Economou’s interests over the public company’s should a conflict occur.