With East Asia’s largest economies — China, Japan and South Korea — committed to reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, offshore wind will play a huge role in developing their hydrogen economies.

Figures compiled exclusively for TW+ by VesselsValue show that Asia’s 5GW of offshore wind today (compared with 19GW in European waters) will increase to more than 600GW by 2050.

That will be nearly triple Europe’s projected capacity of 215GW in 2050.

There are currently just 15 offshore wind farms in operation in Asia: 13 in China and two in Vietnam.

However, China has plans for 230 projects, which are in various stages of development, from planning to operational.

Japan and South Korea are the next two largest potential markets, with 63 and 62 wind farms respectively in stages from planning and pre-construction to fully commissioned or authorised.

With this potential rich vein of projects, Asia’s shipowners and shipyards are gearing up to be in a position to benefit.

South Korea’s Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering was one of the first major Asian yards to benefit from the interest in the offshore wind market.

Last August, US-listed Scorpio Bulkers stunned the maritime world when it announced that it was dumping conventional dry bulk vessels in favour of wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs). It ordered one unit, plus three options, at DSME for between $265m and $290m each, with delivery of the first vessel in 2023.

In April, Samsung Heavy Industries unveiled a “green” WTIV design, which it says halves carbon emissions.

Samsung has received approval in principle for the concept design from three of the largest class societies: ABS, DNV and Lloyd’s Register.

“With IMO 2030 and 2050 approaching, we saw that clients wanted to meet the new requirements for low- or zero- CO2-emission vessels,” a Samsung spokesman tells TW+.

South Korea’s shipyards have been here before. SHI delivered three WTIVs between 2012 and 2015, and Hyundai Heavy Industries targeted the wind turbine vessel market close to a decade ago in the face of competition from China in conventional shipbuilding.

Although the three Samsung WTIVs — Swire Pacific Ocean’s 24,600-gt Wind Orca and Wind Osprey (both built 2012) and Seajacks’ 23,640-gt Seajacks Scylla (built 2015) — are much in demand, the yard failed to secure follow-on orders.

In addition to WTIVs, Asia’s vast future array of wind farms will create significant demand for service craft.

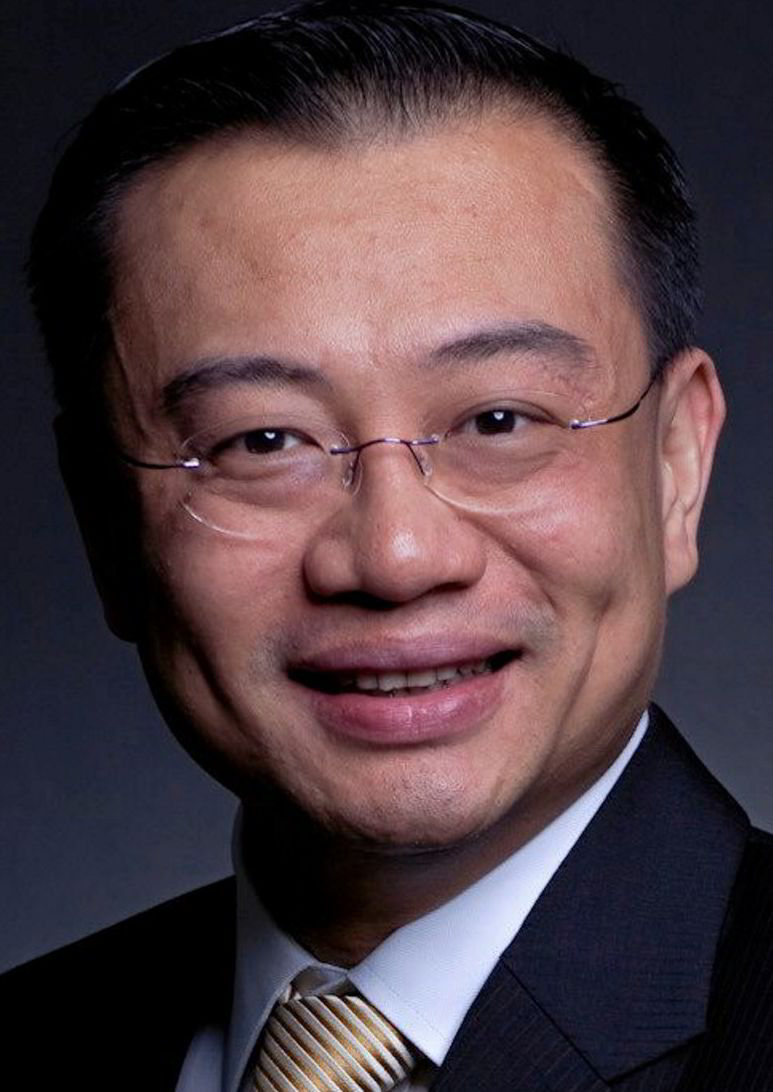

Chan Eng Yew, chief executive of Singapore shipbuilder Strategic Marine, tells TW+: “We see strong interest for our offshore wind vessel products, including CTVs [crew transfer vessels] and SATVs [service accommodation transfer vessels] coming from across the Asian region as many of these countries embrace offshore wind as part of their future energy plans.”

Chan says many shipyards are beginning to focus on this market segment.

Taiwan’s welcoming environment

“While this increases competition,” he says, “there is a large variation in the experience between the yards...”

Chan claims he has been contacted by “several operators” over the past year that have awarded contracts which have fallen through because the shipyard realised it could not deliver on its promises.

There have also been cases in which construction has started but is delayed as a yard is “learning on the job” and the operator typically only realises this several months into the project.

While Asia is expected to be a key hub for offshore wind construction activity this decade, the opportunities for international service providers vary from country to country.

In a report published in late December, Rystad Energy said China has so far focused on supporting local developers and building a domestic value chain, and this is expected to continue towards 2025.

In contrast, Taiwan has proved a key hub for non-Asian developers and service providers in the shorter term. It has welcomed foreign participation, and more than 75% of the developers for Taiwanese offshore projects are European or Western.

The situation is less clear in Japan, which is attracting a number of energy companies, such as Shell, Spanish utilities company Iberdrola and UK utility SSE, which is one of the developers behind Dogger Bank, the world’s largest offshore wind farm, off north-eastern England.

In April, Belgian shipowner DEME unveiled a joint venture with Japan’s Penta-Ocean Construction to focus on building offshore wind farms in Japan.

To date, the traditionally conservative Japanese shipowning community has made only tentative steps into the market.

Mitsui OSK Lines has ordered its first service operation vessel from a yard in Vietnam to service a contract in Taiwan.

NYK Line has been building up its expertise in the sector via a series of partnerships with established European players Van Oord, Northern Offshore Group and Fugro.

Alexander Flotre, Rystad Energy’s product manager for offshore wind, says: “Asia will provide substantial opportunities for international suppliers, but further down the road it could also signal stiffer global competition as local Asian players become seasoned in this new industry and start expanding beyond their home markets.”