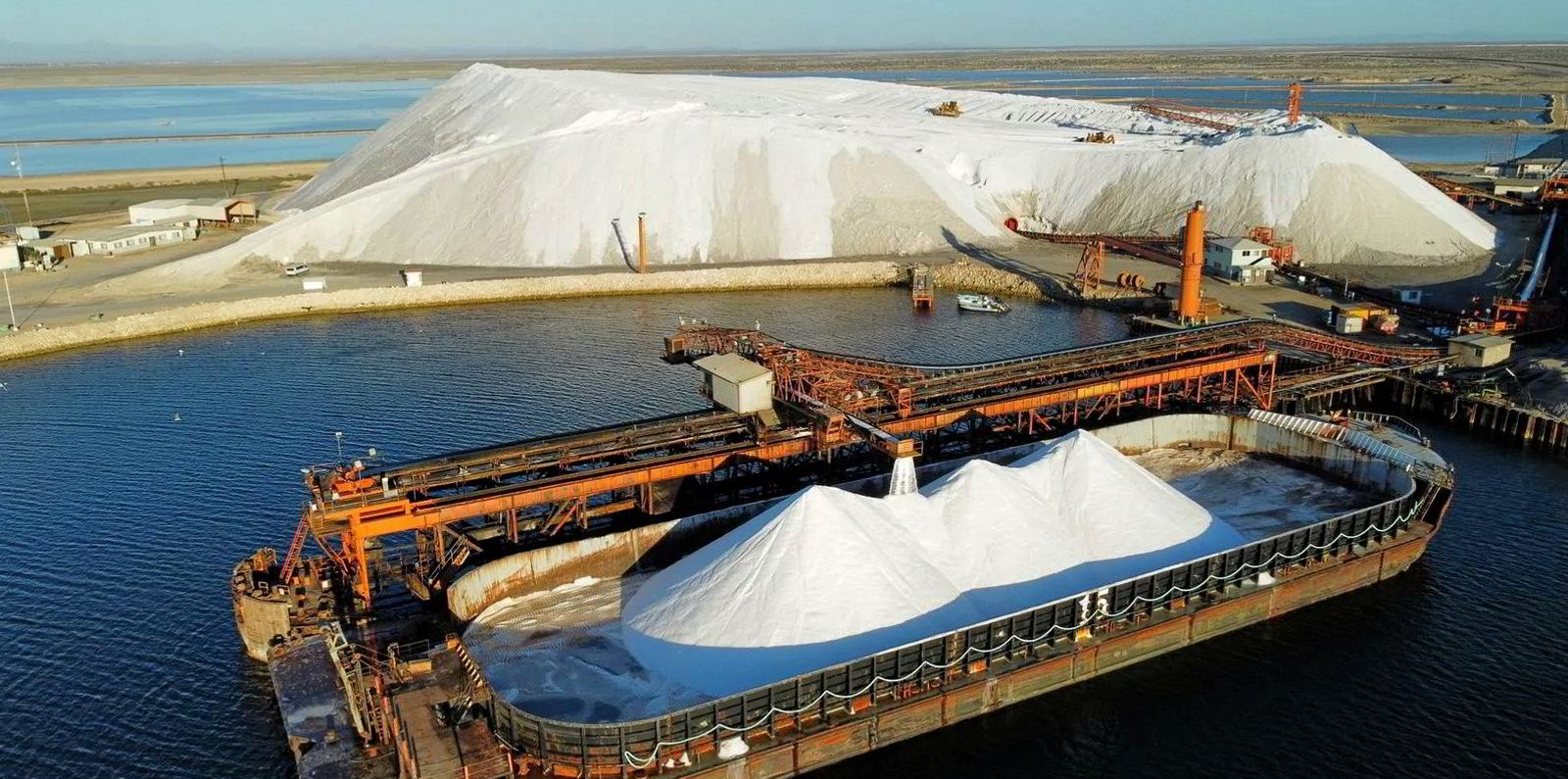

On the Pacific coast of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula, a sprawling operation uses the sun’s power to turn seawater into salt in massive quantities.

And, since 1976, one San Diego-headquartered company has been tasked with running the ships that carry the product of the world’s largest solar salt operation, Exportadora de Sal SA (ESSA), to its customers in North America and Japan.

Like ESSA, Baja Bulk Carriers is a joint venture of the Mexican government and Japanese trading house Mitsubishi Corp.

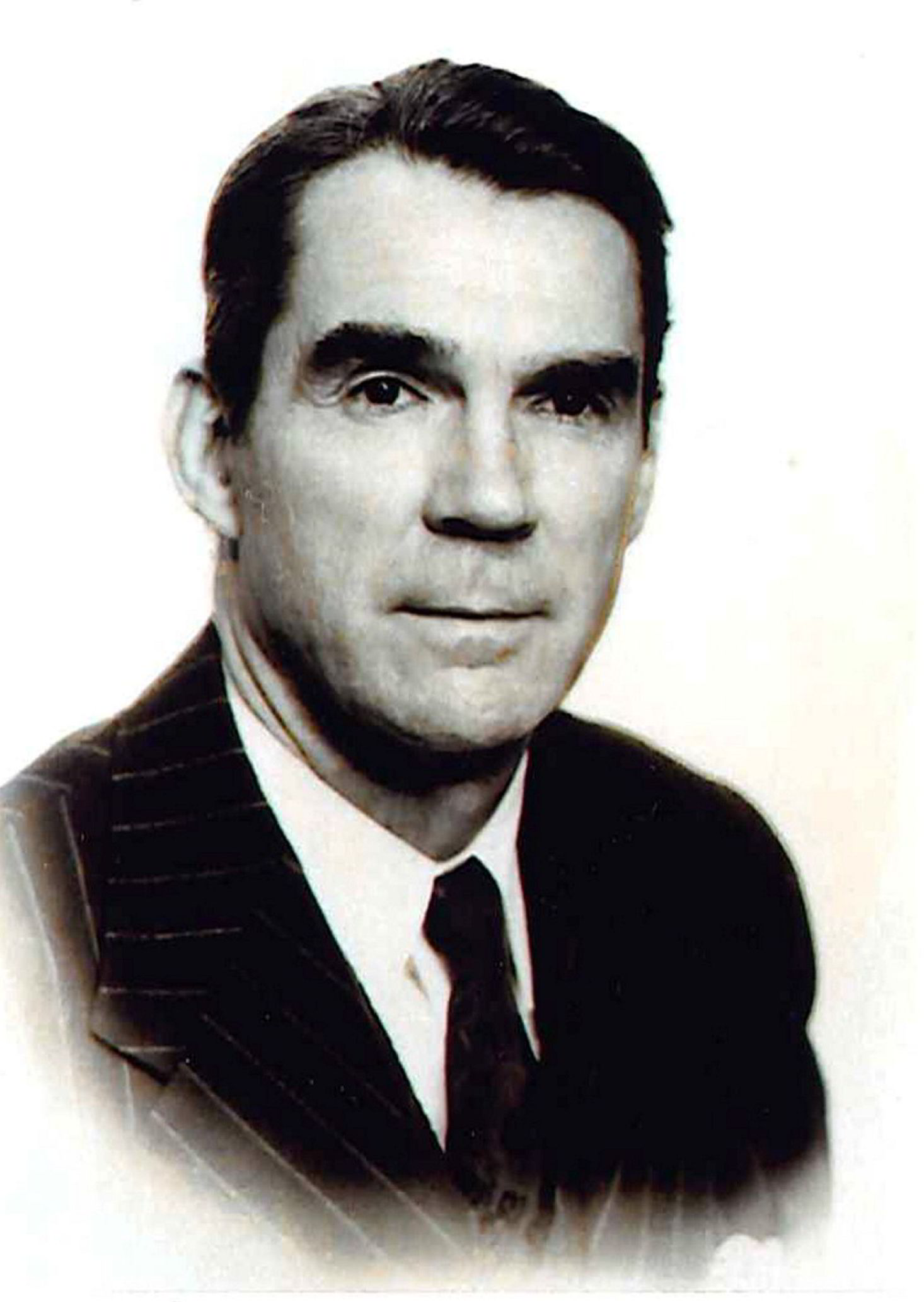

Led by David Rivera Castro, the company operates a fleet of chartered bulkers, including its specialised 62,900-dwt salt carrier Buena Ventura (built 2014).

ESSA has been closely tied to shipping since it was started in 1954.

The company was started by the American billionaire, shipowner and founder of National Bulk Carriers Daniel Keith Ludwig, whose death in 1992 was described by TradeWinds as “the end of an era” of pre-World War II shipping tycoons.

After spotting an opportunity to feed the salt needs of the US west coast, Ludwig found the ideal place to produce it: a large protected lagoon at Guerrero Negro at the midpoint of the Baja peninsula where the water’s salt levels were significantly higher than that of the open ocean.

The soil was already covered in a layer of salt rather than sand, which led to better purity.

There was plenty of waterfront land to create the shallow crystallisation ponds and another key ingredient: wind to help dry out the salt.

“Wherever there’s seawater, there’s salt. But not all places in the world are created equal,” said Rivera, as he explained the history of ESSA and Baja Bulk.

“I don’t know if in the future someone will find something better, but for the past 70 years, Guerrero Negro is in its own class.”

Ludwig won a concession from the Mexican government to run what started out as a small operation, even though it involved the construction of a company town. ESSA’s operation has since grown to a production capacity of 8m tonnes per year.

Eventually, he branched out into new markets in Asia, where there was demand for the commodity in the chemical industry and other sectors.

For such long-haul trades, Guerrero Negro had one drawback. Ludwig was known for preferring the scale of larger vessels, and the bay could only handle handysizes. The tycoon solved this problem by building a transshipment centre on Cedros Island off the Baja California coast.

“To my knowledge, to this day, this is the only company in the world that’s able to ship salt in capesize vessels,” said Rivera, who noted that the most competing projects can handle up to panamax ships in size in a trade that is primarily focused on supramaxes.

Despite its vast coastline, major salt importer Japan had no site like Guerrero Negro, so Ludwig set up a facility near Hiroshima to receive capesize bulkers on the other end of the route.

Mitsubishi Corp became a major partner in the 1960s and bought ESSA from Ludwig in the subsequent decade. Soon after, the Mexican government urged Mitsubishi to bring it into the shareholder rolls as a joint venture partner.

But Ludwig had provided ESSA’s shipping, and Mexican officials proposed creating a shipping company to move the salt facility’s cargoes.

Now, from its base in Southern California, Baja Bulk typically moves 6m to 7m tonnes of salt per year on a mix of vessels.

Solar salt is produced by evaporating seawater in shallow pools, leaving behind the salt.

It is different than rock salt mining, which is produced by mining salt deposits that dried long ago.

“One is dried right now, and the other was dried hundreds of 1000s of years ago,” said Rivera.

Its custom-made Buena Ventura operates up and down North America’s west coast from Long Beach to Vancouver, while a dedicated fleet of chartered capesizes continues to haul cargoes to Japan and other countries in Asia.

And it operates bulkers from handysizes up to capesizes under contracts of affreightment around the world.

Its biggest markets are the chemical industry and US-dominated market for salt for de-icing.

While virtually any bulk carrier can haul salt, Rivera said shipowners can be wary of the commodity because of its corrosive properties.

Some go so far as to limit the number of salt cargoes their vessels can carry in their contracts.

“Some head owners have these clauses in their charters where they say, ‘My vessel will only do one voyage per year or two voyages per year with salt’,” he said.

Rivera said those with experience know that all it takes is a precautionary measure: cargo holds must be protected with a coating like a lime wash, a concoction of lime and milk.

“For those that know that, it’s very easy cargo,” he said. “Very easy to clean, especially if you’re going to have some days between the unloading port and the new loading port.”

Rivera described the salt trade as stable, although he acknowledged that there may be problems in the future.

If climate change lifts water levels in Guerrero Negro, it could impact operations — although that is a potential problem that solar salt producers around the world could face.

And microplastics, which currently do not occur at problematic levels, could become an issue for the third-largest market for solar salt: human consumption.

“The more the levels of plastic grow, the industry will have to figure out how to filter that — to get rid of that. Because if not … then you won’t have purity,” he said.

But for now, Baja Bulk and its sister company ESSA are focused on remaining competitive because salt is a highly freight-sensitive market, and other companies could find cheaper ways to produce the commodity.

Crash course

Under the Baja Bulkers joint venture, the Mexican government picks the company’s chief executive while Mitsubishi chooses the chief operating officer.

The federal government prefers to pick from among the ranks of the public sector rather than from the commercial shipping world.

Rivera, a lawyer with a master’s degree from the University of Chicago, was working in the international trade office of the Mexican embassy in Washington DC when he was called up to lead Baja Bulk in 2021.

He acknowledged that it has been a crash course in shipping.

Rivera said he spent six months getting to know the company, using his legal background as a starting point.

“Being a lawyer, the easiest way for me was to read the contracts — the charterparties — and see exactly how that works, how’s the relationship between owner and charterer, and so on. So that’s how I got to know the legal structure of the company,” Rivera said.

And, in addition to learning from the Baja Bulk team, he also took all the courses that were available at the Baltic Exchange’s Baltic Academy.

Asked what he likes about the job and what its challenges are, Rivera gave one answer to both questions.

As a trade representative, he dealt with imports and exports and saw how geopolitics can shape trade flows.

But it was not until he joined Baja Bulk that he came to see the important role that shipping plays in that picture — even though trade was his job.

As the pandemic showed, it takes maritime disruptions to bring the industry into the public’s perception.

“Day to day, the shipping industry is what moves world trade. I guess that’s something that, if you don’t work in this industry, you don’t realise,” he said. “You don’t even think about it.”

And that means people do not see the complexity of shipping.

Asked what he wants to accomplish as chief executive, Rivera said his role is one in a wider team that keeps the ESSA operation running, with half of its profits supporting the budget of the Mexican government.

“My trench is keeping the deliveries flowing as competitively as possible, and I have to accomplish that mission,” he said.

“If I’m able to do that, then I’ll be able to not only help this corporate team of companies, but also in a way, and with my public service background, help my country, because at the end of the day, the profits from both companies go to the treasury of the country.”