In a prison nestled between flower fields and a US Space Force base in Southern California, seafarer Denys Korotkiy waits out his sentence, but not without a fight.

The chief engineer was convicted in a federal court in San Diego after US prosecutors accused him of ordering crew members of a Liberian-flagged multipurpose ship to dump oily bilge water overboard on the high seas.

As is common in such cases, the US did not charge him with illegal oil dumping; that happened in international waters, after all. But his lawyer, Edward MacColl, has argued in a federal appeals court in San Francisco that the US has no jurisdiction to prosecute foreign seafarers for a related crime: failing to document the discharge in the ship’s oil record book.

Lawyers who have long criticised America’s efforts to prosecute pollution by foreign-flagged ships in international waters hope a decision in the US Supreme Court will open the door for Korotkiy’s appeal of his conviction to succeed.

“The US is wrongfully violating the requirement in the Marpol treaty that requires flag state enforcement for high seas events,” said MacColl, referring to the environmental treaty formally known as the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships.

But others believe Korotkiy’s appeal is a long shot.

The seafarer’s legal problems began in May 2022, when a fellow crew member contacted US authorities days before the 12,800-dwt MPP ship Donald (built 2006) arrived at the port of San Diego.

The whistleblower had reported that Korotkiy repeatedly ordered crew members to dump oily bilge water, the dirty liquid that accumulates in the bilges of a ship, into the ocean without first passing it through equipment designed to take out the pollutants, according to legal documents.

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships: Better known as Marpol, it is the main treaty covering pollution of the marine environment by ships. It was adopted in 1973 and entered into force in 1983.

Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships: Passed in 1980, the US law implements the provision of Marpol.

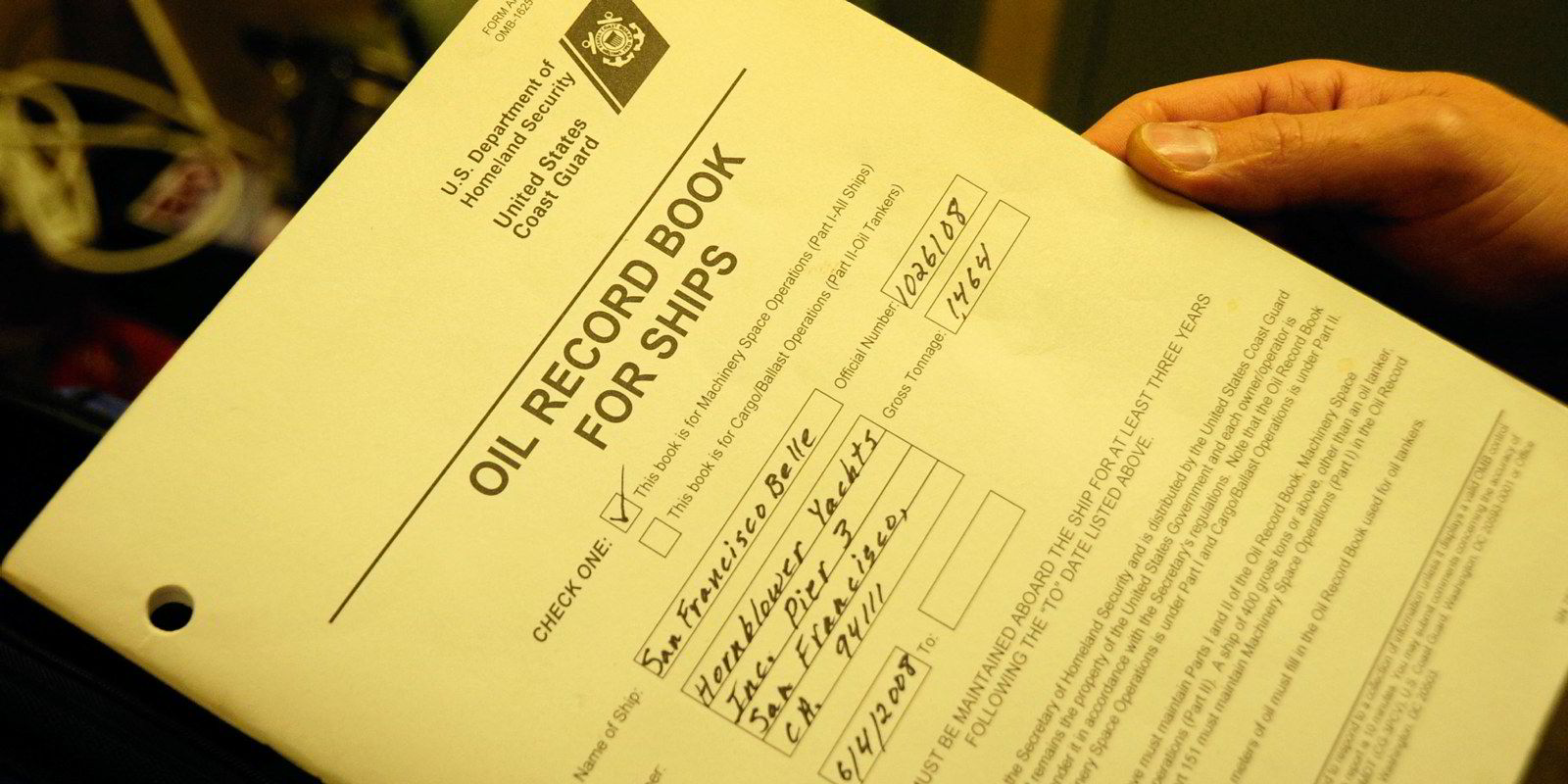

Oil record book: A log on a ship (pictured above) that keeps track of all transfers and discharges of oil or sludge.

The Chevron doctrine: A 1984 holding by the US Supreme Court in litigation between Chevron and the Natural Resources Defense Council that gives federal agencies deference in their interpretation of ambiguous laws.

A resident of the Crimean Peninsula who holds both Russian and Ukrainian passports, Korotkiy was among the crew members who were detained as witnesses while authorities investigated and prosecuted the case. The ship, which has since been renamed O7 Gaja, sailed on. Then in December 2022, he was indicted by a federal grand jury.

The Donald’s manager, Interunity Management, ultimately pleaded guilty. Korotkiy fought the charges against him but was ultimately convicted on three counts in June 2023.

The engineer, who identifies as Russian and is a father of two, could be released from his 12-month prison sentence in April, with credit for good behaviour.

But MacColl — who runs Maine law firm Thompson, Bull, Bass & MacColl — said the federal government is threatening to continue to hold him until he can be deported back to Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014.

In Korotkiy’s appeal before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which only focuses on one of the counts against him, MacColl has argued that failing to maintain an oil record book is no crime at all, at least not in the US when it involves a foreign-flagged ship on the high seas.

And while lawyers representing seafarers, shipowners and vessel managers have made that argument before, and they have been rejected by three federal appeals courts, lawyers told TradeWinds that what makes MacColl’s argument different is his deep dive into the history of US law and the Marpol convention.

Lawyer George Chalos, who heads maritime law firm Chalos & Co and is a long-time critic of US prosecution tactics in shipping pollution cases, said that history makes it clear that the US was well aware that its jurisdiction was limited.

“And they were well aware that, if they discovered some misconduct occurring on foreign-flagged vessels at sea, they were supposed to refer the flag state,” he said.

The International Maritime Organization adopted the Marpol convention in the 1970s with rules covering a variety of types of pollution from ships, but MacColl said the treaty put flag states in charge of ensuring compliance.

The convention became law in the US with the 1980 passage of the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships, also known as APPS, and the US Coast Guard adopted regulations with the details of Marpol’s various provisions.

US prosecutors began to pay attention to oil pollution from ships in the 1990s as mysterious sheens started appearing in Florida waters, according to lawyer Gregory Linsin, formerly with the Justice Department’s Environmental Crimes Section and now a partner at Blank Rome law firm.

Linsin noted this shift led to prosecutions for the submission of inaccurate oil record books at American ports, which relied on regulations that promulgated Marpol and the act that made it US law.

“That theory of prosecution for the inaccurate record book has been tested multiple times in district courts and various appellate courts over the years and has been consistently upheld,” he said.

But MacColl said that Coast Guard regulations that implemented Marpol contained what he described as a “subtle change” from the treaty’s wording: a requirement that an “oil record book” be maintained.

He said the language is clear that it was only meant to apply to foreign ships while they are in the US.

Under Marpol and the US law, “high-seas conduct and record keeping are regulated only by the vessel’s flag state” — Liberia in the case of the Donald.

The lawyer said the history of both the treaty and the law enacting it in the US makes it clear that it was never the intention to make it a crime to fail to maintain an accurate oil record book when a ship arrived at a US port.

“The government’s theory rests on a strained interpretation of one of the regulations issued by the Coast Guard supposedly to effectuate APPS and Marpol that subtly deviates from the Marpol regulations it mimics,” he wrote.

When Marpol came before the US Congress for ratification, then-Environmental Protection Agency director Russel Train testified at the time that the US had urged for a provision in the treaty to allow port state enforcement for high seas pollution. “This was rejected,” he said, according to MacColl’s legal filings.

Marpol intended another way for port states to take action when they suspect a ship has violated Marpol in international waters. MacColl argued they should report the suspected violation to the flag state, and if officials are not satisfied with the action taken, they can file for arbitration at the IMO.

“The international enforcement mechanism would be better,” he told TradeWinds of that option.

“If there are flag states out there that aren’t willing to impose sufficient fines to make sure that shipping companies [are] playing by the rules, take them to the International Maritime Organization — that’s what Marpol says — and sanction them until they impose hefty fines.”

Instead, as the US Coast Guard and Justice Department were transitioning towards using oil record book violations to go after foreign-flagged ships, a 2000 report by the US government watchdog agency General Accounting Office found that referrals to flag states had plummeted, MacColl said in court papers.

The lawyer said the current system, including the Justice Department’s practice of using YouTube videos to entice whistleblowing in exchange for rewards, actually encourages pollution. That is because it incentivises seafarers who witness oil dumping to wait until they can report it to US authorities, rather than telling their employer immediately.

In court papers, lawyers for the US government said Korotkiy falsely indicated in the oil record book that oily waste was transferred to the ship’s bilge holding tank.

They pointed out that he does not dispute the charges of obstructing justice by falsifying records or conspiracy to destroy evidence.

They argued that he only contends that his false entries were made outside US jurisdiction and that he had no legal duty to ensure the oil record book was accurate when he entered US waters.

The Justice Department told the appeals court that the duty to maintain an oil record book requires keeping it accurate because the document is an essential means of detecting violations of the pollution treaty.

And they rejected the contention that Korotkiy was convicted for a crime that happened on the high seas.

“The offence of causing the failure to maintain an oil record book does not occur on the high seas, but rather in the US when a knowingly false oil record book is presented to US authorities at a US port or in US waters,” wrote the team led by assistant attorney general Todd Kim.

However, some maritime lawyers believe the Korotkiy case may also have a chance of succeeding because of a key decision that is currently before the US Supreme Court.

The nation’s highest court has heard arguments in a case involving federal authority in the fishing industry that is a key test of the Chevron doctrine, a 40-year-old precedent that gives deference to a federal agency’s interpretation of a statute.

The Supreme Court, dominated by conservatives who are sceptical of broad federal powers, is expected to significantly alter the rule, if not overturn it.

“I think the current Supreme Court is going to go at least some degree back to saying the agencies can’t change the rules that Congress adopted unless Congress at least gives them some clear indication that they may do so,” MacColl told TradeWinds.

Critics of US prosecutions of shipping companies and seafarers for oil dumping on the high seas also hope the Ninth Circuit will come to a different conclusion than other appeals courts.

But one defence lawyer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, doubted that overturning the Chevron doctrine would make a difference because the rule only comes into play when the wording of laws is ambiguous.

He said there are no unique facts in Korotkiy’s appeal that would lead the Ninth Circuit to go in another direction, especially because the court’s judges are generally viewed as friendly to environmental enforcement.

But the challenge to US prosecutors’ power to go after oil dumping on the high seas raises questions over whether it would take a useful tool out of authorities’ range of options for combating pollution.

SkyTruth, a nonprofit organisation utilising technology to monitor oil pollution at sea, unveiled data in December from its recently launched Cerulean tool that found 1,000 oil slicks from vessels over 12 months, totalling 1.8m barrels of oil.

However, chief executive John Amos told TradeWinds that notable hotspots are present in the waters of the eastern Mediterranean and Asia, contrasting with a relative absence near the US.

He suggested that the US’ pollution monitoring and robust enforcement could be factors in keeping the oceans near the country cleaner.

Linsin, who now works on the defence side of environmental cases, noted that despite a long history of oil record book prosecutions, the cases have not dwindled, which he said is a reflection of the programme’s failure to evolve.

He said in other environmental enforcement programmes, there is a graduated process of enforcement that ranges from administrative penalties, stepping up to civil penalties and then criminal action for the most egregious cases.

But Linsin said oil dumping cases have remained exclusively focused on criminal prosecutions.

“That has significantly distorted our picture of these cases,” he said, citing significant advances in environmental compliance. “Candidly, I think the Department of Justice has lost sight of some developments that have occurred within the industry over this 25 to 30-year period.”