After reporting to their employer that their ship was dumping pollutants into the ocean, the three seafarers were first held on their vessel as US officials investigated.

Then, when German shipowner MST Mineralien Schiffahrt Spedition und Transport struck a deal to allow the ship to sail, they were left behind in Maine, their passports in the hands of the US government.

When they asked a judge to let them go home, they were arrested.

Now, five years after their ordeal, Czech third engineer Jaroslav Hornof and two crewmates are continuing to battle the US government in court with a lawsuit aimed at ending the practice of detaining seafarers as witnesses in pollution investigations.

The case presents a test of prosecution methods followed by US officials for years to enforce oil dumping provisions in the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships — or Marpol.

The lawyer for the three men has argued in a federal court in Maine that their detention amounted to false imprisonment and a violation of the US Constitution’s prohibition on unlawful searches and seizures.

In their lawsuit against the US Justice and Homeland Security departments, as well as the US Coast Guard, lawyer Edward MacColl has contended that their detention amounted to hostage-taking.

The partner at Maine law firm Thompson, MacColl & Bass wrote that the government’s continued practice of holding seafarers amounts to “a form of piracy, and includes involuntary servitude and false imprisonment”.

Now, lawyers for the US Department of Justice are asking a federal court for a judgment against the seafarers’ case, arguing that the men were not held illegally.

While the government has acknowledged that they faced hardships, the lawyers assert the presence of the crewmen in the US was necessary for their important roles as material witnesses in a criminal prosecution.

‘Treated fairly’

“Plaintiffs were at all times treated fairly and decently by federal officials,” wrote lawyers for the US Department of Justice in their bid to throw out the lawsuit.

In many cases, seafarers are willing to remain in the US during prosecutions, staying in a hotel while receiving their salary and holding out for the prospect of a reward. But the Hornof case is emblematic of situations in which maritime lawyers say seafarers wanted to return home but were forced to stay, despite not being accused of any crime.

The lawsuit by third engineer Hornof, fellow engine room crewmen Damir Kordic of Croatia and Lucas Zak of Slovakia is the latest chapter in a series of legal battles that began when their ship was boarded by Coast Guard inspectors in July 2017.

MacColl argued in the lawsuit that the men were the victims of a scheme that included abusing the detention powers of immigration officials, of masking inspections of vessels as investigations of criminal cases with the intention of holding crew and of violating Marpol’s requirement to keep cases of pollution on the high seas in the realm of a ship’s flag state.

Crew as collateral

And he complained that, in such cases, federal officials negotiate only with shipowners and managers, while demanding they pledge members of crew as human collateral.

“Defendant’s agents had no compunction about depriving plaintiffs of their liberty because they had no regard for foreign seafarers or their rights and believed that nobody was going to be able to stop them,” the lawyer wrote in recent court papers.

The three crewmen lodged the latest lawsuit just months after they won $250,000 in whistleblower awards for documenting and reporting illegal oil bilge water discharges from Germany’s MST’s 27,700-dwt slurry carrier Marguerita (built 2016).

Those awards came over objections of the US government after an agreement with the shipowner led it to pay a $3.2m fine against the company, as TradeWinds reported at the time.

- Case title: Jaroslav Hornof vs United States of America

- Court: US District Court for the District of Maine

- Presiding judge: District Judge Jon Levy

- Plaintiffs: Jaroslav Hornof, Damir Kordic and Lucas Zak

- Defendants: US Department of Justice, US Department of Homeland Security and US Coast Guard

- Legal representation: Plaintiffs are represented by Thompson, Bass & MacColl of Portland, Maine. US agencies are represented by the US Department of Justice.

- Trial date: Not yet scheduled

The ongoing lawsuit by the three men seeks compensation amounting to three times the damages that they suffered as a result of being held in the US plus legal and other costs, but it also asks District Judge John Levy for an injunction preventing officials from detaining crewmen or seizing their passports in such cases.

As TW+ reported in 2018, while sailing on the Marguerita, Hornof first confronted the vessel’s chief engineer about his orders to discharge oily water from the vessel. When it did not stop at first, the third engineer went to the captain and MST.

Ultimately, the oily water dumping did cease. MST disclosed the evidence gathered by Hornof and his co-workers to Liberia, the ship’s flag state, and to the US, where the company was already on probation for another pollution case.

MacColl has argued that Marpol requires Washington to defer to prosecution by the flag state, and US officials knew Liberia was investigating the pollution incident when the vessel arrived in Maine.

But he argued that instead of starting a dialogue with Liberia, US officials “secretly conspired to disrupt the lives of the plaintiffs and other crew members and to violate their clear rights in order to leverage fines, reap personal glory and take credit for the candour and work already done” by Hornof.

Lawyers for the Department of Justice argued that the notion that Marpol violations should only be prosecuted by the flag state, and pollution in international waters did not involve a violation of US law, is incorrect.

Required to enforce

They said the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships — the US law that codifies Marpol — requires officials to enforce the treaty.

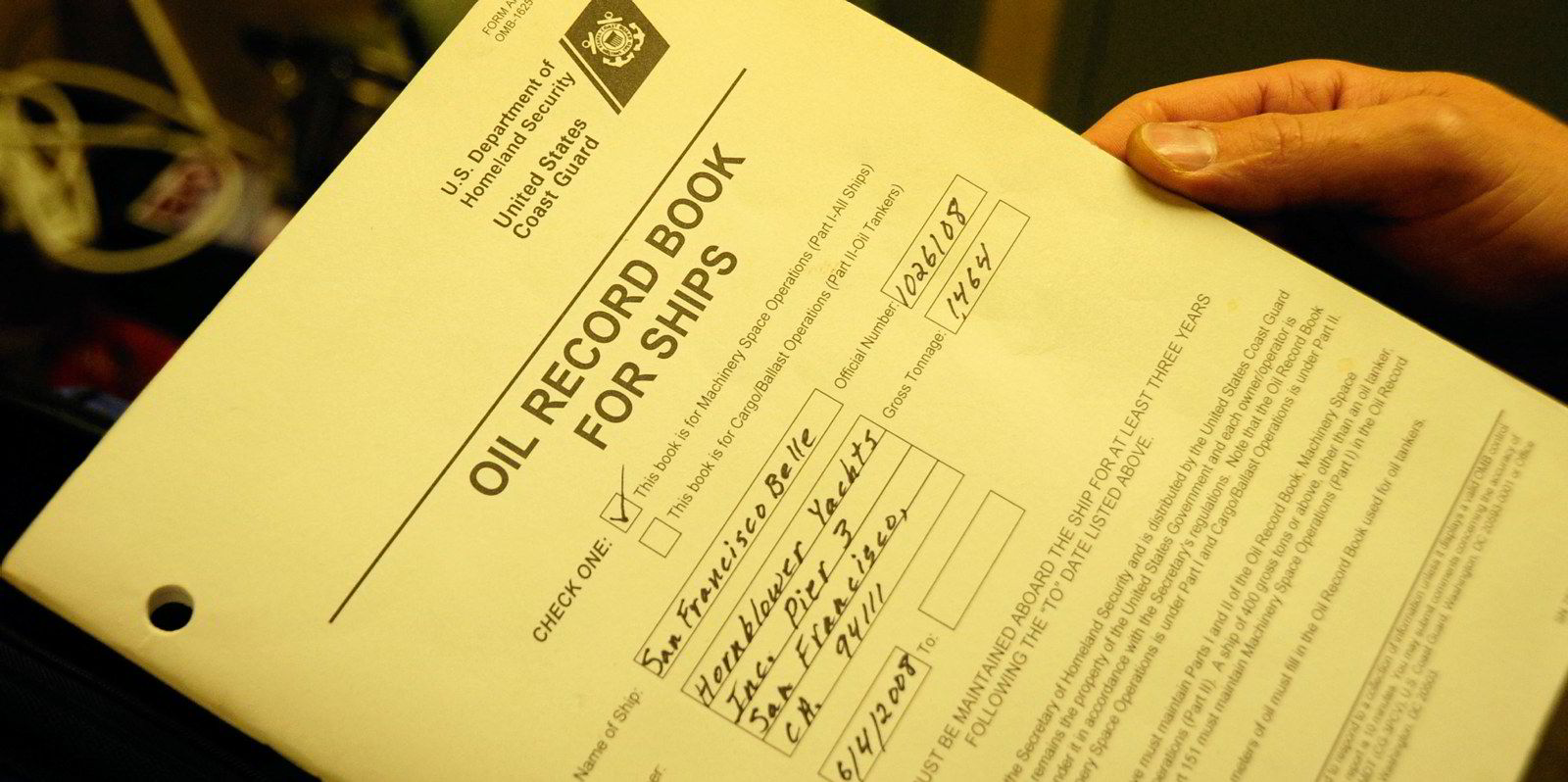

And the US contended that the Marguerita’s oil record book, which contained a note that it may contain incorrect information after Hornof’s allegations, violated the law whenever the ship entered US waters.

When the Marguerita arrived in Maine, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials initially gave the crew shore passes. They soon revoked them after Coast Guard officials inspected the vessel and claimed to discover the pollution incident previously reported by Hornof, the lawsuit alleged.

The ship was then detained, with all of its crew prohibited from leaving the vessel.

Reasonable

Lawyers for the Department of Justice have argued that withdrawal of the shore passes was reasonable.

“Foreign nationals do not have a right to be admitted into the US ... There is no guarantee that a foreign crewman will be permitted to land in the United States,” US lawyers said in court papers.

US officials later struck an agreement with MST that allowed the ship to leave, but required nine crew members to stay behind in Maine. Their passports were confiscated, the lawsuit claimed.

“Plaintiffs were not parties to, and did not approve or consent to, the illegal agreement,” MacColl wrote.

But lawyers for the US pointed out that the agreement with MST meant that the men’s employment contracts were extended, and they received their salary, lodging, a per diem allowance and medical benefits.

MST was to ask crew members to surrender their passports, and let the government know if they refused. It did not tell the government that any of the crew did not want to turn over their passports, the lawyers for the Department Justice argued.

Then, when the crew members turned to the courts to ask to be released, prosecutors filed applications to have them arrested as material witnesses.

Hornof, for example, filed a motion in court asking for permission to return to Prague in July 2017 to console his pregnant wife after her mother died. Prosecutors responded by filing an application to have him arrested.

‘Material’ testimony

The Department of Justice has asserted that the men’s testimony was material to a criminal proceeding.

And its lawyers said prosecutors only sought the arrest warrants when they had to. As long as the crewmen agreed to voluntarily remain in Maine to assist the investigation, they did not face arrest.

That changed when they asked to leave.

“The prosecutors accurately represented to the court that no other means was available by which to secure the witnesses’ presence at trial,” the Department of Justice said in its filings.

Defendants’ rights

But for prosecutors, the men needed to be in the US for more than just to help the case. The Department of Justice argued that the seafarers’ rights had to be balanced against those of MST.

The US Constitution gives criminal defendants the right to confront the witness against them in court.

The Department of Justice said: “The First Circuit [Court of Appeals] has interpreted the US Constitution’s Confrontation Clause to mandate that the government use all reasonable means to prevent a present witness from becoming an absent witness. Should the government fail, a criminal defendant should not pay the price.”

A key question in the case is whether the detention of Hornof and his colleagues violated their rights under the Fourth Amendment — the constitutional provision against unreasonable searches and seizures.

But the Department of Justice has argued that Fourth Amendment rights only come into play after a seafarer has “developed substantial connections” with the US.

“They do not apply to searches and seizures of aliens in international waters,” the government’s lawyers wrote.

And they argued that the government agencies involved in the investigation of the Marguerita operated within their powers. The Coast Guard had to investigate evidence of a crime, CBP officials had to keep track of the Marguerita crew while they were in the country, and the Department of Justice had to obtain evidence.

“Each of the involved agencies was fulfilling its proper role,” the US lawyers wrote.

Constitutional protections

MacColl fired back that the Fourth Amendment does protect seafarers.

During the detention, the seafarers cooperated with the investigation and prosecution, testifying twice.

A judge finally allowed them to leave in September 2017, two months after they arrived, but they were required to return to testify a third time, which prevented them from signing onto a vessel, their lawyer has claimed.

Their lawsuit has alleged that the men have been driven from their oceangoing careers as a result of the case, and they suffered distress as a result of their alleged wrongful detention.

“The plaintiffs seek judicial relief so that they may consider returning to their careers as seafarers without the risk that they will again be held as hostages, human collateral or involuntary servants in violation of their basic human rights, and so that other crewmen will not suffer as they have suffered,” MacColl wrote in court papers.