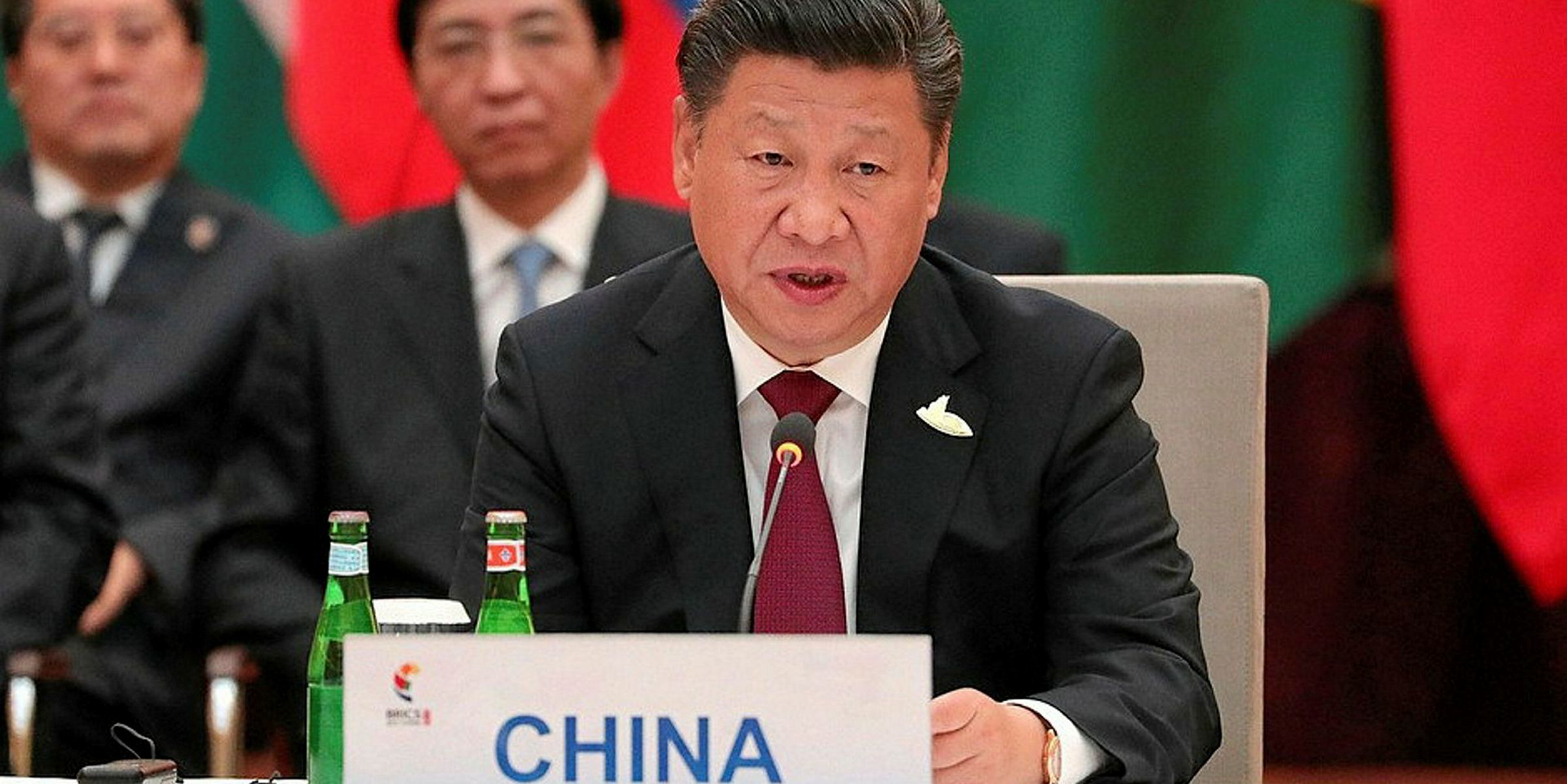

By the end of the month, Beijing will give the world a new look at its freshly polished Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) at what is planned as China's biggest international summit this year.

The global transport infrastructure investment project remains a cornerstone of the foreign policy of Chinese leader Xi Jinping, and is even written into the Communist Party's constitution.

Last month's National People's Congress (NPC) reaffirmed the centrality of the BRI, with its massive price tag (often cited at $900bn), its long roll of participant countries (115 at last count), and its land and sea routes linking China more tightly to every corner of the globe (except some corners in the US, Japan, Australia and India).

Arctic ambitions

Chinese maritime branding has even extended to the Arctic, where the Polar Silk Road gives a Chinese spin to what Westerners and Russians call the Northeast Passage and the Northern Sea Route.

Xi's foreign minister Wang Yi announced at the finish of the NPC that The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation would convene in Beijing in late April. Pomp, festivity, and unnaturally blue Beijing sky are no doubt in store, but the past year was one in which the BRI's key Indian Ocean links came under fire, in the case of Gwadar literally so.

Although it reaches well into the Mediterranean now, the BRI is at its most belt-like along the Indian Ocean, where it loops through four crucial junctions at Djibouti near Aden, at Gwadar just outside the Persian Gulf, at the tip of Sri Lanka, and at Port Klang on the Strait of Malacca.

Each of these loops offers serious unresolved challenges for the BRI as a whole.

The rule of law

In Djibouti, the Doraleh Container Terminal is at the centre of a bitter legal fight after the government reneged last year on a 30-year concession to former operator DP World and handed the facility over to China Merchants Group.

Djibouti's military strategic significance as a permanent US military outpost gives China's foothold there a high profile. But the more dire issue commercially is the BRI's challenge to international rules for dispute resolution.

Both the London Court of International Arbitration and the High Court of Justice in England have ruled in favour of DP World. Djibouti has ignored them despite contractual jurisdiction clauses.

From China's point of view, however, sovereign litigation disputes could be less a bug than a feature of the BRI. Xi's ambition is to hand over jurisdiction of all BRI disputes worldwide to two courts in the People's Republic, one at Xi'an for the shoreside BRI and another at Shenzhen for disputes over Maritime Silk Road projects.

The Great Game

Gwadar in Pakistan near the Iranian border is perhaps intended to be the buckle of the BRI rather than just a loop.

Besides competing with Dubai as a man-made deepwater port for regional transshipment traffic, Gwadar will benefit from a huge hinterland when and if the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPRC) develops commercially. The $60bn CPRC is meant to create a robust overland link from troubled Xinjiang in north-western China to the Indian Ocean, giving China an extra outlet to round the world trade that does not depend on the Strait of Malacca bottleneck.

Some overland CPRC cargoes have already begun topping the Khunjerab Pass into Pakistan, but Gwadar is by no means ready for high-volume business

But that puts the Indian Ocean port in play as part of a perpetually replayed conflict, the Great Game for control of central Asia. Not only has Gwadar itself been the scene of violent unrest over the project, its huge hinterland exposes it to border conflicts as far off as Kashmir, and to global disapproval of China's concentration camp regime in Xinjiang itself.

Some overland CPRC cargoes have already begun topping the Khunjerab Pass into Pakistan, but Gwadar is by no means ready for high-volume business. Last month, the Pakistani senate heard complaints that the present port lacks even facilities to fuel buses connecting the planned port to the local airport.

Loosening up the Straits

The same idea of breaking the bottleneck and giving China multiple supply routes underlies the pipeline projects that give China's southwestern city of Kunming an outlet to tankers on the Bay of Bengal at the Myanmar port of Kyaukphyu.

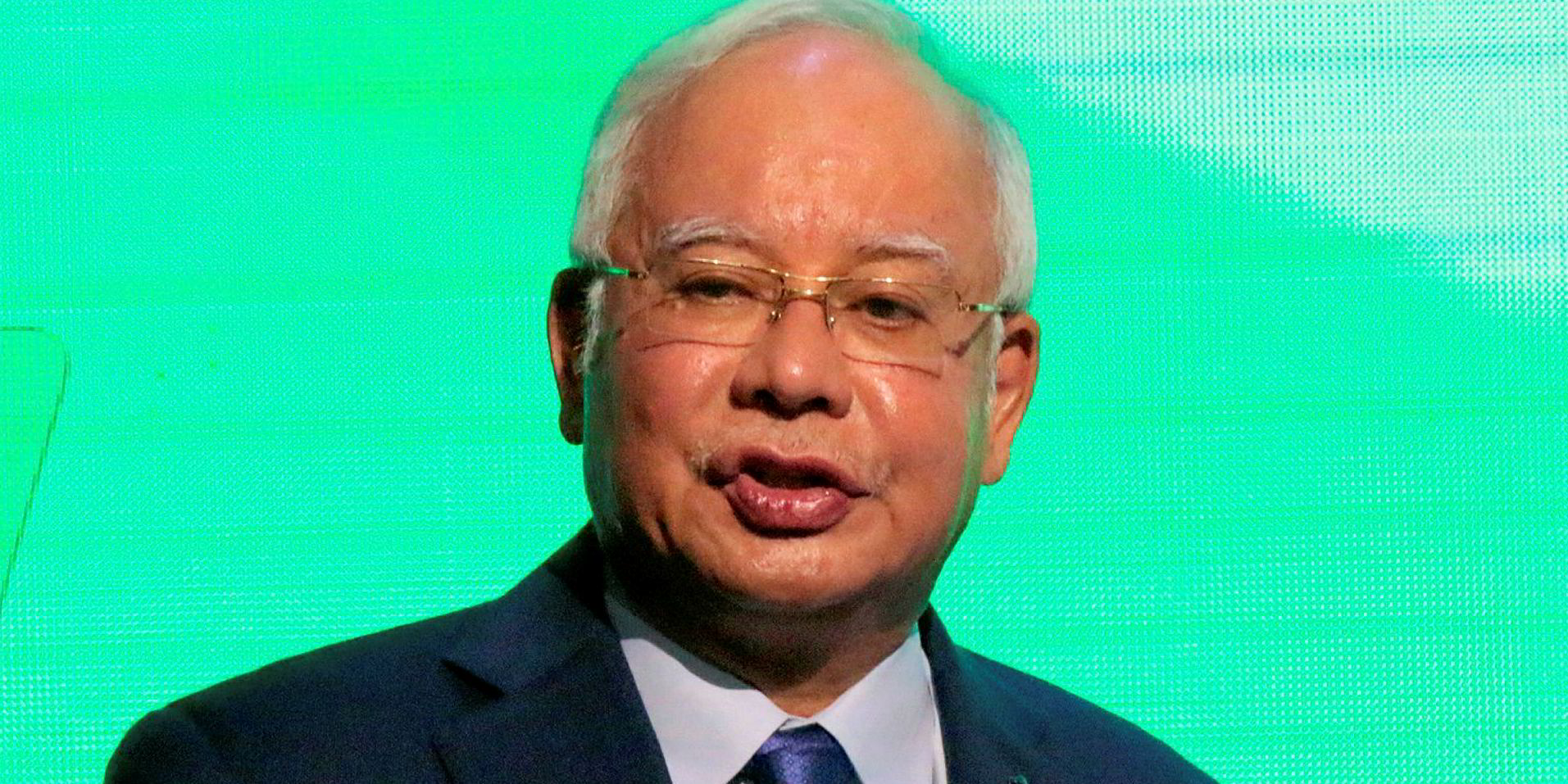

The school of thinking is also reflected in the $20bn East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) signed by former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, which besides connecting regional population centres was meant to create a viable overland alternative to the Strait of Malacca at Port Klang, at least for containerised cargo.

As in projects in Nepal and Sri Lanka, the Malaysian rail link has proved vulnerable to the political instabilities of China's junior partners in BRI deals. Cancelled in January by Najib's successor Mahathir Mohamad as too expensive and linked to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal or 1MDB scandal, the project is under renegotiation in the hopes of salvaging it in a limited form.

This article is part of the Maritime Asia business focus. Read the full report in the next weekly edition.