The US has tightened the enforcement of international sanctions in a way that will increase compliance costs for many shipping companies.

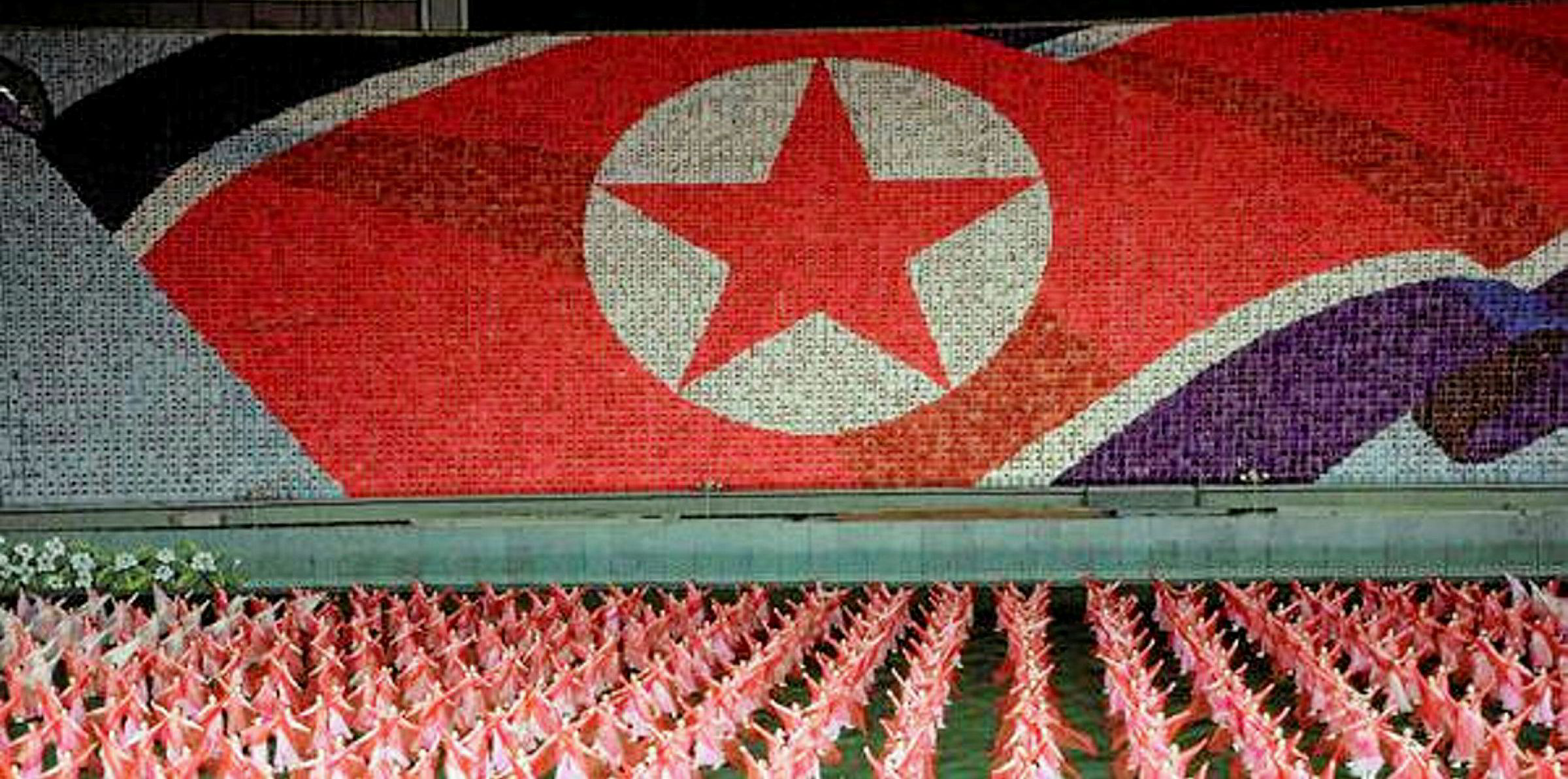

Without changing the wording of sanction orders, the Department of the Treasury has issued two advisories detailing how companies should avoid dealings with Iranian, Syrian and North Korean shipments.

“There are several organizations that provide commercial shipping data, such as ship location, ship registry information and ship flagging information,” says one advisory. “This data should be incorporated into due diligence best practices.”

According to Ami Daniel, chief executive of maritime risk-analysis firm Windward, those advisories mean industry players need to adopt advanced data tools to monitor whether their counterparties are engaged in sanctioned trades.

The general industry practice has been to check on whether the vessels and counterparties one deals with are on any sanctions list or have any suspicious ownership information, port calls or use of flag states.

“That’s not enough,” Daniel warns. “You should actively screen suspicious behaviours [such as] ship-to-ship transfers, dark activity [turning AIS off] and identity tampering. Doing this screening on the world fleet ... is not manually feasible.”

Lawyer Jonathan Epstein, a partner at Holland & Knight in Washington DC, points out that American expectation of compliance has grown in line with the amount of available information.

“Because the technologies are available, the government is assuming people are using them and should be using them,” Epstein tells TradeWinds. “Certainly, the information is there — if you are willing to pay for that.”

A sophisticated vessel-tracking database can cost tens of thousands of dollars, on top of legal and other costs. US authorities are not expected to take these compliance costs into consideration when it comes to enforcement, though.

Don’t expect sympathy

“Compliance always costs money,” says Seward & Kissel partner Bruce Paulsen. “If you are going to the Office of Foreign Assets Control [OFAC] saying that compliance costs too much, you are not going to get too much ... sympathy.”

The OFAC is the Treasury’s enforcement agency for sanctions.

The sanctions against Iran, Syria and North Korea apply to US and foreign shipowners, shipmanagers, vessel operators, brokers, flag registries, oil companies, port operators, classification societies, insurers and financial institutions.

The US could officially identify companies and vessels as sanctioned entities by putting them on the list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs). But some are also put on the so-called “name and shame” list without actually being sanctioned. Both measures are powerful, even though those “named and shamed” will not face official penalties, Epstein says.

In general due diligence, those on SDN and “name and shame” lists will be labelled high-risk entities to financial institutions, according to Epstein, seriously hampering their daily operations.

Overall, the lawyers suggest companies make as much effort in compliance as possible, as the authorities would take this into consideration if a company somehow were unknowingly to become engaged in sanctioned activity.

“You may do 10 things and it may help you reduce the penalty,” Paulsen says.

Epstein adds: “You need to be extremely careful about what you are doing and understand the risks. Mitigating those risks [would be] money well spent.”

The OFAC has much discretion over when and whom to penalise — which does not help shipping companies when it comes to compliance.

Since April, the US has sanctioned several Greek and Italian tankers for shipping oil from Venezuela to Cuba, without explicitly stating in advance that such activity is sanctionable.

“If you are engaged in those marginalised trades, you need to be very, very careful,” Epstein says.

Having practised sanctions laws for more than 20 years, he adds: “I don’t think I have had more difficulty [knowing] what the US policy is. I am not sure if the US knows what its policy is. I don’t know if the professional staff and senior government officials in the White House are necessarily aligned. [This] creates enormous difficulty for [compliance].”

Paulsen agrees the enforcement is not always consistent. “Sometimes you [have] got tough talk and not enough enforcement. Sometimes you have a lot of enforcement but not tough talk,” he says. “The idea is to keep people nervous and off balance.”