Ship operators’ need to cut the level of sulphur emitted from the fuels they burn by 2020 is focusing minds on cleaning up their act — and the cost of doing so. They might want to start thinking a bit wider.

The debate largely revolves around the cost of fitting and using exhaust scrubbers versus burning low-sulphur marine gas oil (MGO), which currently costs about $300 per tonne more than high-sulphur heavy fuel oil (HFO).

Confusing the comparison of depreciation against the higher price of MGO is the potential for the price difference between MGO and HFO to increase substantially, due to market shortages caused by so many vessels suddenly switching to the lower-sulphur 0.5% option in a little over a year’s time.

But there is a longer-term issue that is not addressed at all by these calculations: cutting greenhouse gas emissions, particularly CO2.

And while dealing with these issues, wouldn’t it be nice to look for a cut in fuel costs rather than an ever-increasing bill? Not possible? A dream or future fantasy? Not necessarily, but it will take a leap of faith.

Wouldn’t it be nice to look for a cut in fuel costs rather than an ever-increasing bill? Not possible? A dream or future fantasy? Not necessarily, but it will take a leap of faith.

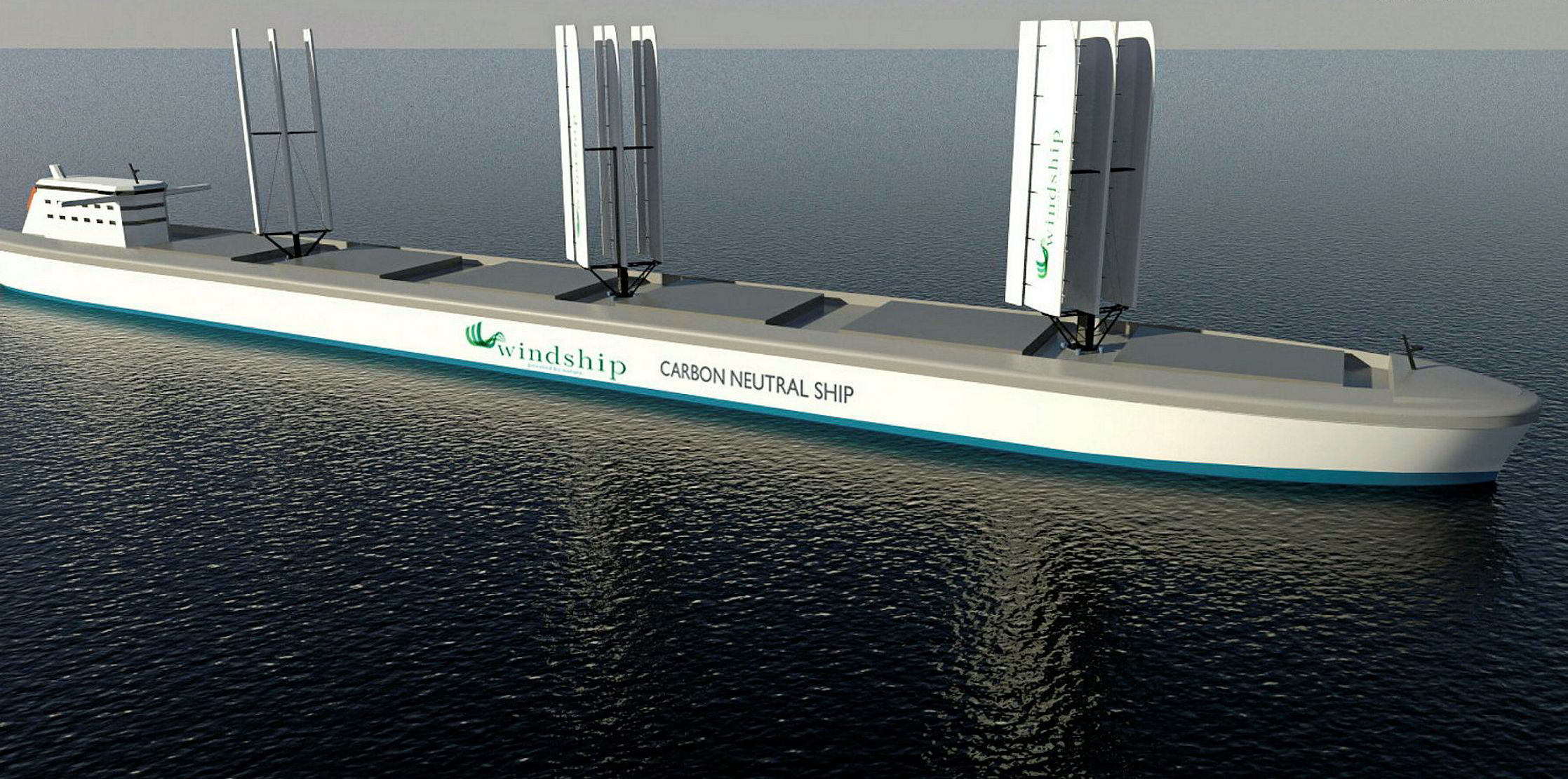

Carbon-neutral design unveiled

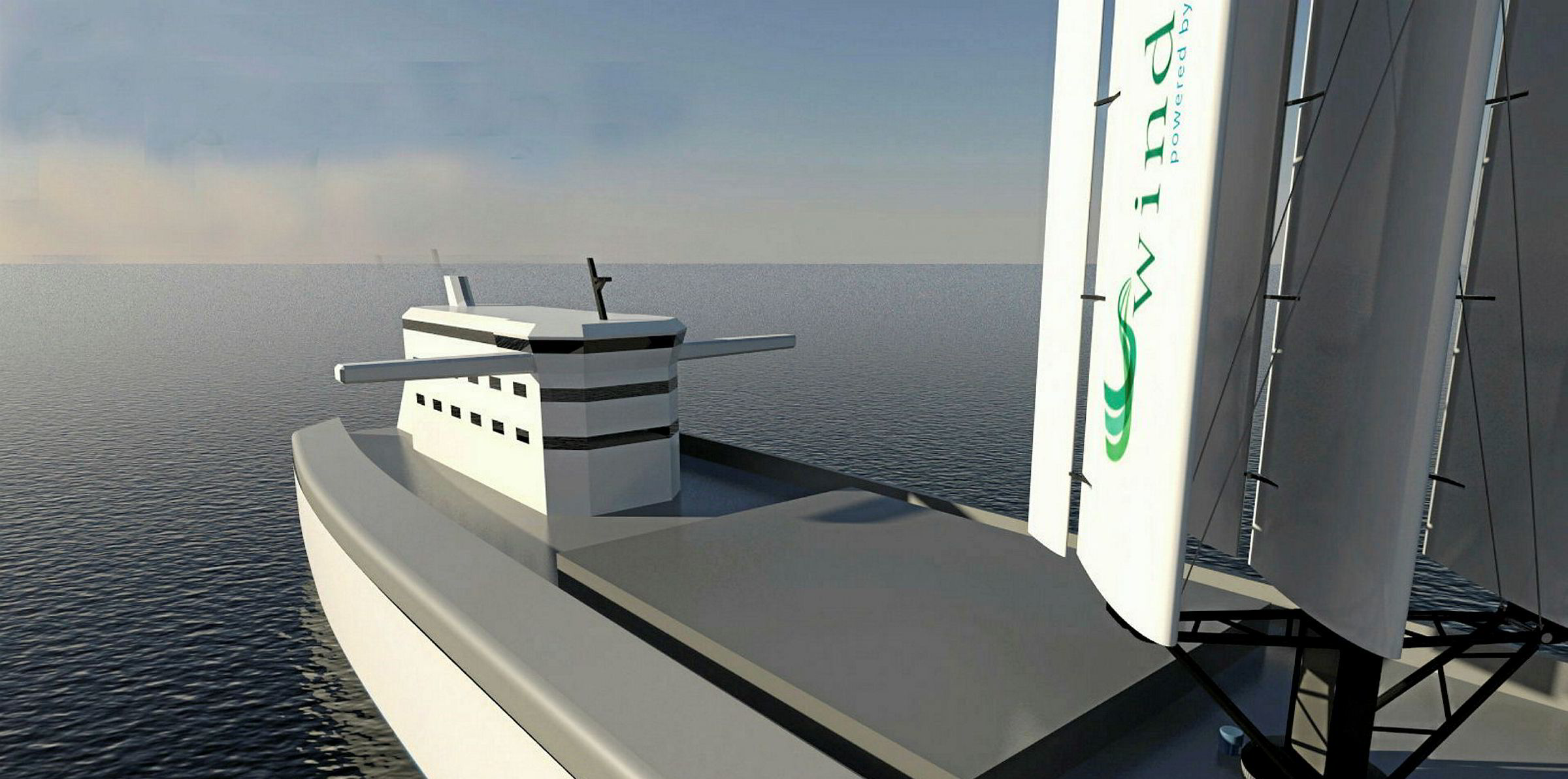

Windship Technology last week unveiled its carbon-neutral ship design. It claims the bulker can reduce fuel consumption by 30% by catching the power of the wind in 35-metre-tall rigs, plus save a similar amount from permanently slower steaming at 11 knots, and at least a further 20% from an optimised streamlined hull using twin variable pitch propellers.

Directors of the London firm say the ship will still need a diesel engine for 20% of the time when it is headed into the wind or in calm conditions, but they foresee that element being covered in future by burning biofuels derived from waste.

The technology can be retrofitted too. And the good news is that converting existing vessels to carry sails can more than halve the cost of all fuel use by a bulker. A rough price of $10m for three rigs allows for depreciation in around two years, and then savings of $7m to $12m per year for the rest of a ship’s life. So, say, 15 years and it would be in the $100m region, at least.

Windship acknowledges that previous attempts to develop wind sail systems have muddied the water for a naturally sceptical shipping industry. But it says its technology is proven in the yacht racing and aviation worlds. The larger the ship, the better, from 30,000 dwt up to Valemax, with a 120,000-dwt vessel able to sail fuel-free in 30-knot winds.

The weight of the rigs has been reduced from 350 tonnes to 125 tonnes by switching from steel to proven, composite materials used in wind turbines. In any case, they help prevent vessel roll, thereby improving safety and performance. DNV GL is working on classification rules for the technology, and grain charterers and stevedores at Rotterdam have said they will not have problems loading cargoes. Banks are under pressure to show that loan portfolios have green credentials and so can be expected to be positive about lending to retrofit projects.

So, what’s not to like? Well, understandably, most shipowners want to see the system work in real life before plunging into technology that is not yet proven in commercial shipping and does carry some pretty high costs.

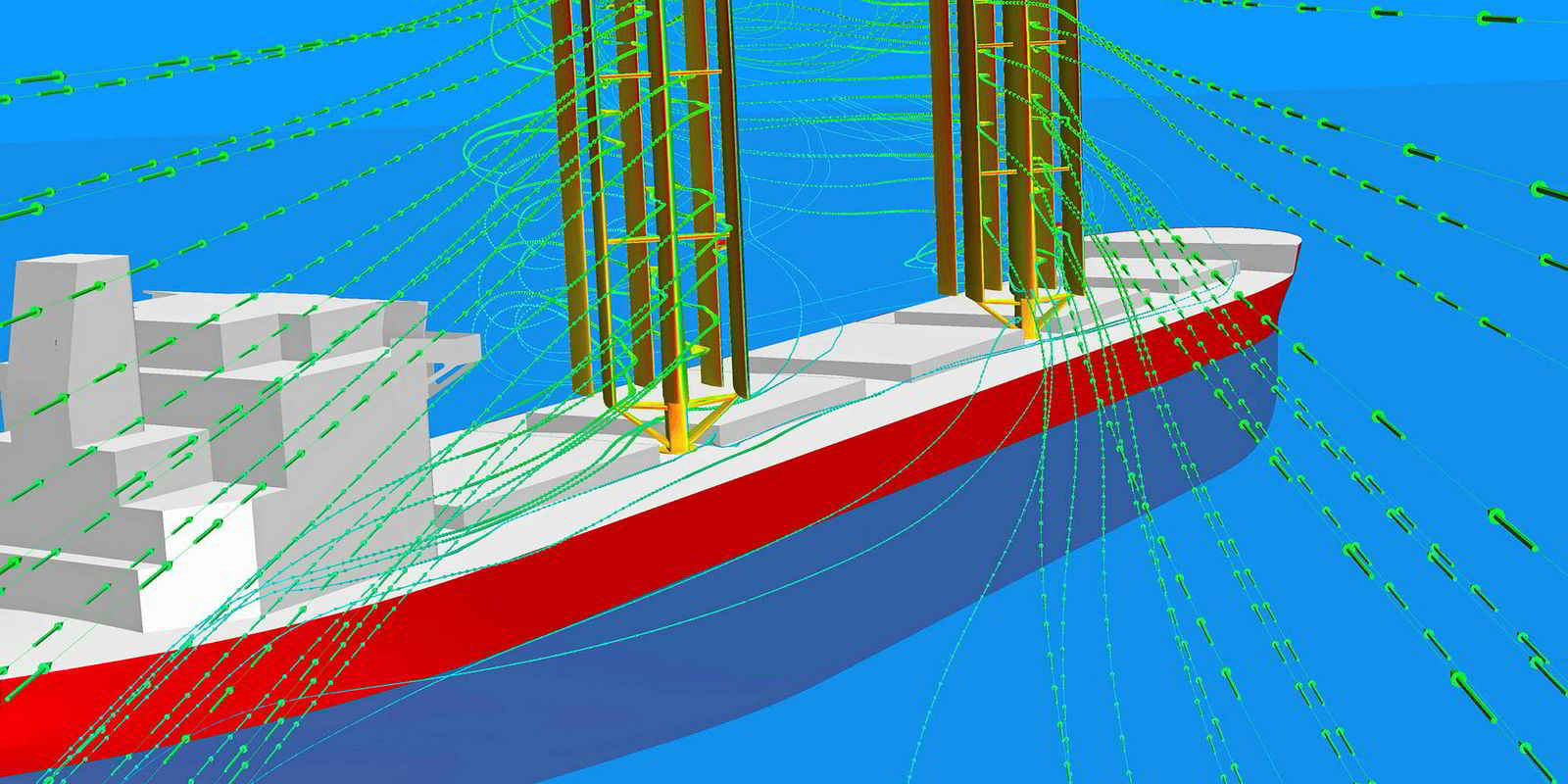

Windship says it has teamed up with a major, as yet unnamed, player in the shipping industry to undertake computer modelling this autumn on which a conversion can be based (this is the same process undertaken to develop winning yachts for the America’s Cup). The aim is for modelling to lead to construction of prototypes within two years and then trials, potentially with a number of ships.

Two weeks ago, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report arguing that urgent, unprecedented change is needed to stop global temperatures rising more than 1.5C from pre-industrial levels — a limit it now says is essential to avoid calamitous natural change that threatens human survival.

Ambitious but feasible

The target is ambitious but feasible. To achieve it, carbon pollution would have to be cut by 45% by 2030 and come down to zero by 2050. Shipping legislators currently aim to halve the industry’s carbon emissions by 2050 — which is nowhere near enough, and there is no clear plan as to how to do that. So greater action is needed, or it could be forced on the industry.

The week before the IPCC report, 34 major shipping groups pledged a commitment to pursue CO2 emission reductions at the Global Maritime Forum in Hong Kong. Among those signing up were shipowners Euronav, GasLog, AP Moller-Maersk, Norden, Fairmont Shipping, Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, Pacific Basin and MISC, as well as traders Cargill and Trafigura.

If that pledge is anything more than hot air, it is time for some of them to step forward with cash in their hands and test out putting sails back on ships — for their own and everyone’s benefit.