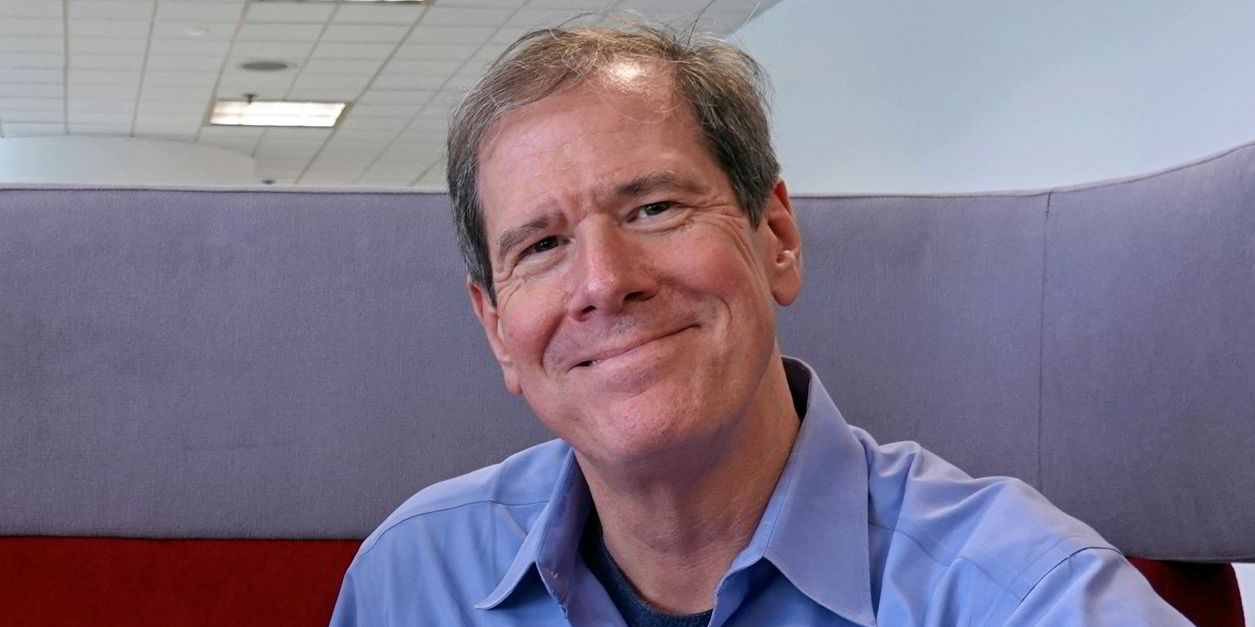

Tidewater chief executive Quintin Kneen has overseen an acquisitions drive that has made the company one of the fastest-growing offshore players in the world.

But despite its high-profile acquisitions of companies and fleets of ships, Tidewater retains an appetite for more.

Big-ticket deals in the past decade include the $1.25bn acquisition of GulfMark Offshore in 2018, the $190m takeover of Singapore-headquartered Swire Pacific Offshore, or SPO, in 2022, and a $577m deal to buy 37 high-spec platform supply vessels from Norway’s Solstad Offshore in March 2023.

A key attribute Tidewater looks for in mergers and acquisitions is the ability to increase its span of control over vessels on the water, provided those ships maximise earning potential and/or contribute to the individual profitability of each vessel through economies of scale.

Speaking to TradeWinds in Tidewater’s Singapore office, Kneen said the M&A deals were struck when companies and assets could be cheaply acquired. Tidewater was able to fund its purchases — at a time when traditional financiers were offshore-averse — because of a long-standing relationship with DNB Bank.

“We also raised some money in the Norwegian debt market. That was facilitated by the fact that the Norwegian credit markets are generally more welcoming than any other place in the world to offshore credit,” he said.

Even then, Kneen noted, “financing was very expensive, and we had to give them a lot of collateral”.

The hunt for M&A candidates continues, Kneen said.

- 2018: $1.25bn acquisition of GulfMark Offshore

- 2022: $190m takeover of Singapore-headquartered Swire Pacific Offshore

- 2023: $577m deal to buy 37 high-spec platform supply vessels from Solstad Offshore

“I’ve been focused on companies in North America and South America, principally because the acquisitions that we made earlier were in Asia, West Africa and the North Sea.

“And so, just to balance out the global position of the fleet, I’m looking for acquisition candidates in those geographies. Those are also two geographies that have strong cabotage restrictions. The US is very strong. Brazil is a little bit more flexible.

“But I wouldn’t rule out an acquisition anywhere else,” he said.

Offshore supercycle

Tidewater may be on the hunt for M&A candidates, but Kneen admits that with the offshore market in full recovery — like many of his industry peers, he believes it is on the cusp of a supercycle — the relative bargains it enjoyed previously are no longer available.

“There are candidates out there, but when the market strengthens, like it is now, what happens naturally is that everybody’s expectations start to get too high as it relates to the price per boat.

“A boat that would have cost $16m two years ago now costs $25m to $30m.

“The market is good, but it may not justify that price,” he said.

Kneen also notes that it is harder to convince companies or their shareholders to sell.

“Two or three years ago, people were more willing to transact, they were willing to negotiate. In today’s market, nobody is as desperate as they were five years ago,” he added.

“I think the banks would like for the companies to find a solution to their excess of leverage, but they are not demanding the solution immediately.

“People are making enough money to service their debt. They see an upside in the market, so there is a willingness to hold on to tonnage, a willingness to wait it out,” he explained.

“And as a result, the prices are higher.”

Kneen stresses that Tidewater’s expansion moves are not growth just for the sake of growth.

“The evolution that I’m trying to drive today relates to making sure that our global footprint is appropriate for a global offshore company,” he said.

“That’s why my acquisition focus right now is in North America and South America, where I feel we are relatively light.

“But I also believe that in a five to 10-year timeframe, we’re going to see offshore wind come to become more economical, and so I would expect to see Tidewater more focused on offshore wind activity,” he added.

Integration challenges

The hard work of buying a company often begins after the deal has been signed and press releases issued.

Then integration starts, as senior managers attempt to merge two entities with different cultures.

There are layoffs, usually at the company being subsumed, which leads to employee mistrust of their new management.

Kneen readily admits that Tidewater, having acquired GulfMark Offshore in 2018 and SPO in 2022, experienced integration pains.

“All integrations are difficult. SPO was no exception,” he said when asked if there were any challenges in assimilating a traditionally run, family-owned company based in Asia with a US corporate.

The bulk of the senior managers of SPO left after the acquisition deal was concluded. Managing director Peter Langslow retired, as did others, while some stayed with the Swire Group.

Joanne Ang, who joined SPO as financial controller in 2017 before becoming its global head of human resources in August 2021, stayed on. She was promoted to become Tidewater’s managing director for Asia Pacific in January this year.

Ang describes the transition period as being “a difficult time”.

“Culture was one of the biggest hurdles the legacy Swire team had to overcome,” she said.

As Tidewater Asia Pacific’s new area financial controller and human resources director, Ang had to oversee the reduction of the Singapore office headcount from 130 people down to 30, as well as the adjustment of pay scales for staff and seafarers down to those of Tidewater.

“People are not blind. They could see I was always interacting with Quintin and the new management, so they thought I held all the secrets, and that I was the gatekeeper to their futures.

“There was a lot of uncertainty and anxiety, a lot of mistrust in the management,” she said.

Ang noted that the key to making the transition a success ultimately lay with communication, keeping employees informed at all times about what was happening and why.

“I needed to first convince them that the new management team could be trusted. Two years on, if I reflect on everything that Quintin and his team have said, I am in a position to say, hey, they were genuine from the beginning.”

In her new role, Ang is one of six Tidewater managing directors in charge of a specific region who look after vessels based in that region.

In Ang’s case, she is responsible for the end-to-end operations of a fleet of 20 to 25 offshore vessels. Under her remit are the Australian and South East Asian offshore sectors, as well as several vessels that are working in the Taiwanese offshore wind sector.

“I am responsible for putting the vessels to work, getting the contracts, placing the right people on the vessels, all the technical aspects, repairs and maintenance, and making sure that we are paid by the charterer for the work we have done,” she said.

“There continues to be strong demand for our vessels in Asia Pacific. The question now is how can we be more efficient.”