A new frontier is opening for shipowners in the waters off the US.

A growing list of developers of offshore wind projects is queuing up to meet demand for clean energy, and they will need vessels to build and then support turbines in US waters.

While it is early days for this nascent corner of the market protected by the Jones Act shipping law, optimism is mounting for the bounty that awaits, thanks to growing regulatory certainty, a US president keen to push forward carbon-neutral electrical power and project advancements in the Atlantic.

That is not to say challenges are not ahead, with some regulatory questions still lingering and uncertainty over how fast the project pipeline can advance.

But with the financial close of a project by Vineyard Wind, allowing the start of construction of the first major offshore wind farm in US waters, things are getting real in the Atlantic north-east and other project advancements.

"It's a huge opportunity for the domestic maritime industry, and it's a huge opportunity for the clean energy future of this country," said Jennifer Carpenter, the chair of the offshore wind committee at Jones Act coalition American Maritime Partnership.

Project pipeline

According to a September report of the Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory, there is at least 35.3 GW of offshore wind project capacity at various stages of development in US waters.

Some 15 projects are in the permitting pipeline, and there are more leases down the road.

Adding energy to the effort is a call by US President Joe Biden for 30 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, and state governments are aiming to procure 40 GW by 2040.

After confirmation late last year that the waters where this bonanza is growing are subject to the Jones Act cabotage law, much of these projects' marine needs will have to be met by US-built ships, although foreign vessels can perform some of the work.

That could fuel construction of an alphabet soup of specialist ships, including service operation vessels (SOVs), crew transfer vessels (CTVs), wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and a new breed of feeder vessels.

"Offshore wind is the hottest thing going in the renewables sector," said Jeff Andreini, vice president of the new energy services division at US maritime conglomerate Crowley. "And we have all of our attention focused on that area."

Crowley is responding to requests for proposals for SOVs and CTVs, which it would construct at US shipyards. Andreini said he could see a market for 20 SOVs to meet offshore project needs, in addition to 60 to 70 CTVs.

The company set up its new energy services unit in January of this year in a bid to leverage Crowley's expertise in marine and landside logistics to support the renewable energy community.

Andreini is gearing up to move from his current base in Houston to the company's newly opened office in Providence, Rhode Island — which will put him in the heart of the offshore wind service community.

The new office is just a small part of Crowley's running start at the offshore wind sector. Already working on offshore wind since 2012 with a fleet of oceangoing tugs and offshore construction barges to serve projects, the company has partnered with Esvagt, a leading global player in wind farm SOVs, to enter that segment.

Port infrastructure

And the company has struck a deal to buy land in the city of Salem, Massachusetts, where it will develop an offshore wind service terminal with Vineyard Wind as an anchor tenant.

"We are offering a full-service turnkey package," he said.

But Jones Act vessels will take time to build, and will cost more than foreign-flag ships.

Legal and industry experts said that after legislative action late in January and rulings by US Customs & Border Protection that followed, some key regulatory questions have been answered, laying out some ground rules for how foreign-flag tonnage and Jones Act-qualified vessels can operate in the sector.

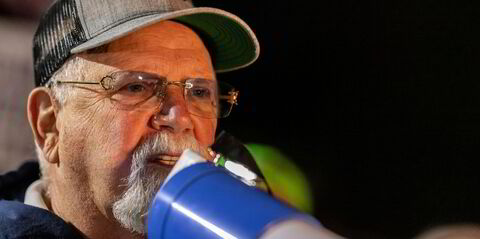

Charlie Papavizas, a maritime lawyer at Washington DC-based Winston & Strawn, said there are some issues on which US Customs has yet to clarify some lingering questions.

But he does not think regulatory questions led any wind project developers to hold fire.

"People have thought all along, and I continue to think, that it's really a speed bump, not a roadblock," he said. "There's plenty of things foreign vessels can do, and that opens up the business to the world market instead of what's in the US-flag fleet."