If ambition and inspiring words could solve the climate crisis, then the world would be closing in on a solution. Although some of the rhetoric must be written off as posturing by those covering their backs, there is also a great deal of sincere concern and desire to act among people who provide and use shipping services worldwide.

Much of that was on display last week in New York at the annual Global Maritime Forum meeting, and at other Climate Week events across the US east coast.

But the problem is about more than words. It is about putting those words to work and achieving real-world actions and solutions. Just as new UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng discovered in recent days, if your shiny new theoretical policy lacks credibility, it will sink faster than the Titanic.

Pieces of the puzzle

In shipping, there is no lack of activity. Retrofitting ships with technologies to improve sailing efficiency is surging ahead in the run-up to the introduction of landmark carbon emission rules at the start of next year. Greater efficiency lowers fuel use, saves money and cuts pollution, whatever you are burning.

However, while every saving is valuable, it will only cut fuel consumption by a maximum of 15% to 20%. In the context of the aim for zero well-to-wake carbon emissions by 2050, it is only a minor part of the puzzle.

Green fuels are not yet available at anything like the required scale, nor is the engine technology to use them if they were. And, when they are available, and the ships are built, the market will still face the critical question of price.

With zero-carbon fuel likely to cost between two to three times today’s dirty oil bunker fuel, the problem will be hard to bridge unless carbon is priced aggressively.

Carbon pricing has long been a contentious and insolvable problem for the global shipping industry, and the International Maritime Organization in particular. Discussions in the first half of the last decade saw it rejected; killed off by industry opposition to any tax, developing nation reticence, and refusal of the US to sign up for any sort of global fiscal deal.

In its place were born the unwieldy operational rules, the Carbon Intensity Indicator. While well-intentioned, they are proving badly designed and regarded by many as unfit for purpose in their current form.

Yet there is virtually unanimous agreement across the providers, users and regulators of shipping that a progressive carbon pricing mechanism is the vital next step. By progressively adding to the cost of carbon-based fuels over time, green fuels are made comparatively more competitive, and funds raised can be recycled into capacity building and compensation projects.

Over the next nine months, IMO has committed to updating its climate change strategy, and carbon pricing is firmly on the agenda. At environment committee meetings in November and then critically in June next year, IMO member nations have the chance to act on their intentions.

Some countries remain implacably opposed. Shipowners and charterers must use their voices to lobby their flag partners to embrace the initiative since time is running out.

Electrifying the debate

Carbon emissions continue to climb. They will rise this year again, as they did last year, as seaborne trade grows. And they are set to continue upwards at least until towards the end of this decade. It is a long, long way from zero emissions.

Francesco La Camera, director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency, warned this week: “If we don’t change dramatically the way we produce and consume, 1.5C is close to vanishing.”

Kitack Lim — the secretary general at the IMO — and his executive must use all their skills to win over the doubters in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Its leadership needs to electrify the debate and help focus minds on the stakes in play.

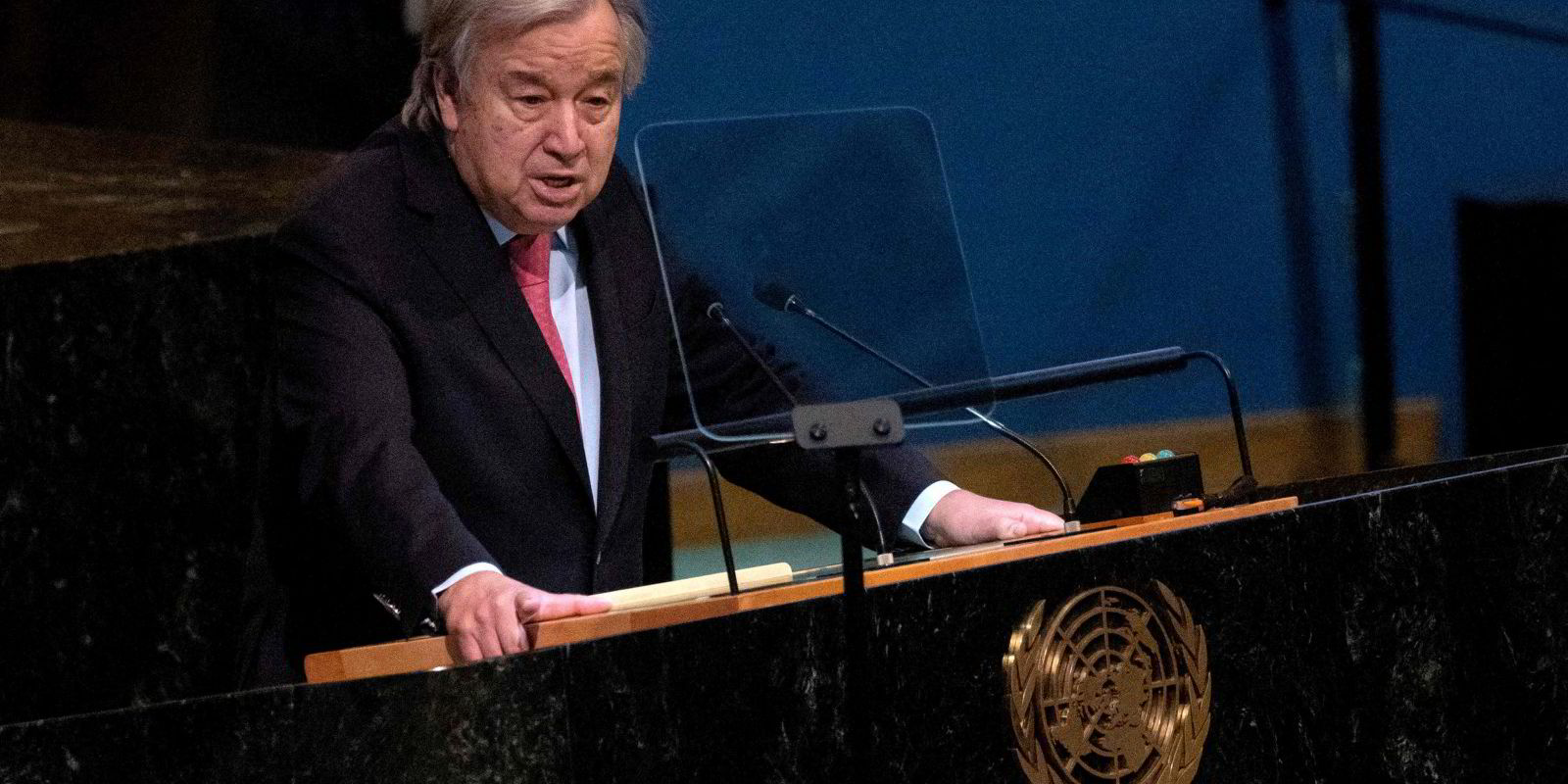

They should take the lead from their boss — United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres — and, like him, step up the rhetoric to incite action.

“The climate crisis is the defining issue of our time,” Guterres said in his address to the UN General Assembly last week. “It must be the priority of every government and multilateral organisation. It is high time to put fossil fuel producers, investors and enablers on notice. Polluters must pay.”

Words do have power, and that power must be put to good use.