I spent one day in Glasgow last week at COP26 in a darkened church hall on the River Clyde that had stain glass windows painted with pictures of men building ships.

It was a stone’s throw from the once mighty merchant yards of the Govan Shipbuilders such as Fairfields, which is now constructing destroyers for the Royal Navy under the BAE banner.

I was there to listen to a debate on the Just Transition, the sister to Climate Action, where speakers outlined the need to ensure social fairness alongside decarbonisation.

They recalled the closure of many Scottish shipyards, such as the local coal mines, had been a difficult time for the workforce.

How to halt this happening again — and what about the global south, which has played little part in creating global warming yet is in the firing line of floods and heatwaves?

The same message of equity came from the Just Transition Task Force, which knits together the International Transport Workers' Federation with the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS).

All of this as the main COP26 climate talks hatched a final — imperfect — text. But one that pointed ultimately in one direction: forward to energy transition.

China might not have sent its head of state Xi Jinping to Glasgow but having Joe Biden and the US at the table more than made up for that, especially coming after the wilderness years of Donald Trump.

Yes, the speed of change envisaged in the final wording of the COP26 text is not enough to keep world temperatures at the aspirational 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Yes, there needs to be a hell of a lot of movement to turn hopes into actions, but certainly the words "fossil fuels" as a threat to mankind appeared for the first time on a COP document.

There is only one message that shipping can take from the summit in Glasgow and that is that it must get on board the decarbonisation bandwagon and go green — fast.

Green corridors

We now have a helpful new promise from 19 nations to develop Green Shipping Corridors, while Norway, the UK and US committed to net-zero shipping by 2050.

Yes, individual actions create their own difficult issues but they also create vital momentum, especially when the International Maritime Organization is currently still anchored to a target of only halving emissions by 2050.

Kitack Lim, the IMO secretary general, promised the ICS’ Shaping the Future of Shipping conference in Glasgow to “upgrade our ambition”. We will now see what happens at next week's Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting.

There are still loads of "how to" issues, not least those around the use of LNG for main ship engines: fuel of the future or a wasteful distraction from renewable-produced ammonia or hydrogen?

Shipowners are split about this, their decision-making not made easier by the growing concerns expressed at COP over leaks from natural gas of methane.

An agreement was hammered out in Glasgow to cut methane emissions from oil and gas extraction and flaring by 30% come 2030. That is not nearly enough of course but it is a compromise like everything else that happened at COP26.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that is said to be up to 80 times worse for the environment over a 20-year period than CO2 itself.

We also have key maritime governments — such as Greece — continuing to raise all sorts of concerns about the European Union's intention to include shipping in its Emissions Trading System.

Certainly, the markets have reacted to the COP agreement with European carbon prices jumping to record levels at the start of this week at €66 ($88) a tonne, up from €55 a month ago.

Rules for a new global carbon market were put in place at the summit that will allow the creation of a centralised system available to both public and private sectors.

Questions remain about old carbon credits dating back to the Kyoto Protocol being allowed into the new scheme amid widespread concerns about the climate benefits claimed from the "offsets".

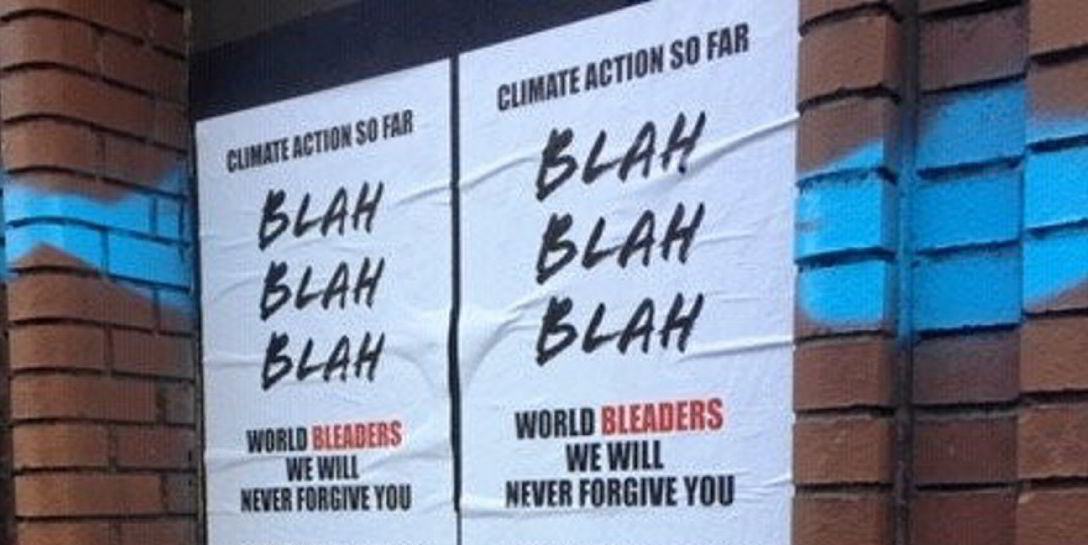

Greta Thunberg called it blah, blah, blah and Guy Platten, secretary general of the ICS kind of agreed: "We've had a lot of challenges and declarations and targets. I think we need to get on and do stuff now."