The coast off Nigeria is the “most dangerous in the world”, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) has warned.

The London-based organisation, which monitors global piracy, did not make this comment in recent days — although it might well have done.

The warning came 16 years ago and has been repeated in various forms many times since.

As recently as 2016, IMB director Pottengal Mukundan talked of “unacceptable violence” against ships and their crews off Nigeria.

He looked forward to a special conference in Lome, Togo, in October that year to tackle West African maritime security.

But four years on, seafarers working off West Africa are still facing unacceptable levels of violence.

The most recent quarterly IMB report showed a 40% increase in the number of kidnappings in the Gulf of Guinea.

In the first nine months of this year, 85 crew members were kidnapped and 31 held hostage on their own vessels.

A total of 112 vessels were boarded and six were fired upon. As current IMB director Michael Howlett put it: “Crews are facing exceptional pressures due to Covid-19 and the risk of violent piracy or armed robbery is an extra stress.”

The problems since then have got worse, if anything, with daily attacks being reported.

Already winning the war?

On 2 December, a reefer vessel controlled by Laskaridis Shipping was fired on off Bayelsa in Nigeria. Pirates attacked in two skiffs but armed guards on the ship responded and the master took evasive action and escaped.

A week earlier, a product tanker off Ghana was fired on and boarded, while six robbers with guns came on board a general cargo vessel off Conakry Anchorage, Guinea.

Before now, sea piracy was high, but it has reduced to a situation where I can say we are in control

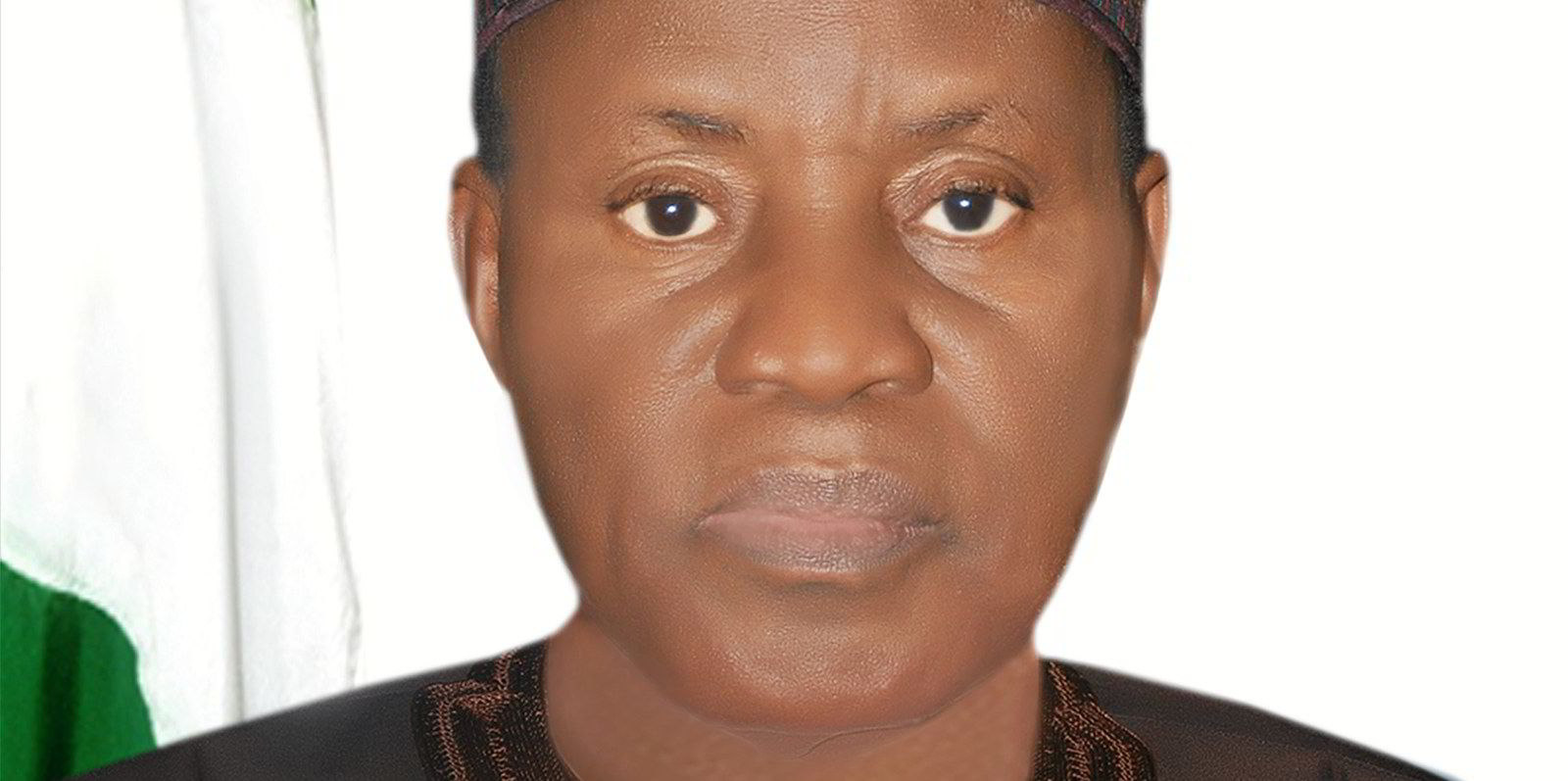

Nigerian defence minister Bashir Salihi Magashi

In mid-November, 14 Chinese crew members were kidnapped from the 48,127-dwt heavylift vessel Zhen Hua 7 (built 1998) off Sao Tome.

These are a few of the incidents reported to the IMB that have triggered calls from shipping organisations such as Bimco for urgent action.

Last year, parliament passed the Nigerian Suppression of Piracy and Other Maritime Offences Act 2019. No convictions have yet been made under the legislation, although a trial is pending of 10 people charged with attacking a Chinese trawler in May.

Nigeria has also set up a Deep Blue Project, under which a command, control and communications centre has been established to coordinate action against piracy.

In addition, the government claims to have assembled an array of helicopters, interceptor boats and drones ready for action.

Alarmingly, the defence minister, Major-General Bashir Salihi Magashi, has claimed to be already winning the war against piracy.

“The navy is already containing the situation. Before now, sea piracy was high, but it has reduced to a situation where I can say we are in control. The implementation of this [Deep Blue] project will further help in this direction,” he was quoted as saying in local newspaper reports.

Understandably, he is concerned that Nigeria gets criticism for any attack in the whole of the Gulf of Guinea — a huge area, which extends beyond his country’s national borders.

But there must be wider worries that Magashi is over-optimistic and believes Nigeria and its neighbours can win this piracy war on their own.

This has not been the case in former kidnapping hotspots such as the Gulf of Aden, where it took an international flotilla of naval vessels to bring the situation under control.

Solution lies on land

The Danish government, for one, is convinced an international show of strength is vital. Defence minister Trine Bramsen believes a “two-legged approach” is needed, with local action, but also “an international coalition of the willing — and hopefully a military presence — in the region”.

The longer-term solution, of course, is land-based. Piracy — as off Somalia — is at least partly driven by unemployment and poverty. Nigeria has oil wealth but high levels of deprivation.

The fear is that attacks will grow as the current “dry season” makes them easier to launch. It’s now or never for Nigeria’s Deep Blue strategy, but surely an international naval force is needed to bring this long-running problem to a halt.