The number of students petitioning against Cass Business School changing its name because of its links to slavery had passed 3,650 this Wednesday.

Sir John Cass certainly did have a direct connection with the transatlantic slave trade.

But why did the Cass name have to be changed now, after years as a highly regarded brand in the list of business schools? It was surely no secret to those involved in the establishment where the Cass cash came from?

A Cass graduate, Brian H Robb, wrote the petition submission on the change.org website. It argues that the management board acted in a high-handed way by failing to consult properly.

The petition goes on to claim that the move has undermined the position of those who graduated under the Cass brand, and that the name should remain the same, or financial compensation should be given to past graduates.

These arguments all have some merit, but in light of the wider issues — race, class and privilege — asking for money strikes a strange note.

The school, which hosts the Costas Grammenos Centre for Shipping, Trade and Finance, announced this month that it would immediately be renamed the City’s Business School. A permanent name is still under consideration.

The decision, initiated by Cass’ parent, City, University of London, came as the Black Lives Matter protests swept first across the US and then Britain.

Statues of slavers, or institutions named after them, have been in the firing line. Unsurprisingly, the issue has a particular resonance in traditional trading centres such as Bristol and London, where many of those who shipped, insured or financed the slave trade were based.

Is it fair to say — as trade union Nautilus International does — that the rock-bottom wages paid to some seafarers are a modern version of slavery?

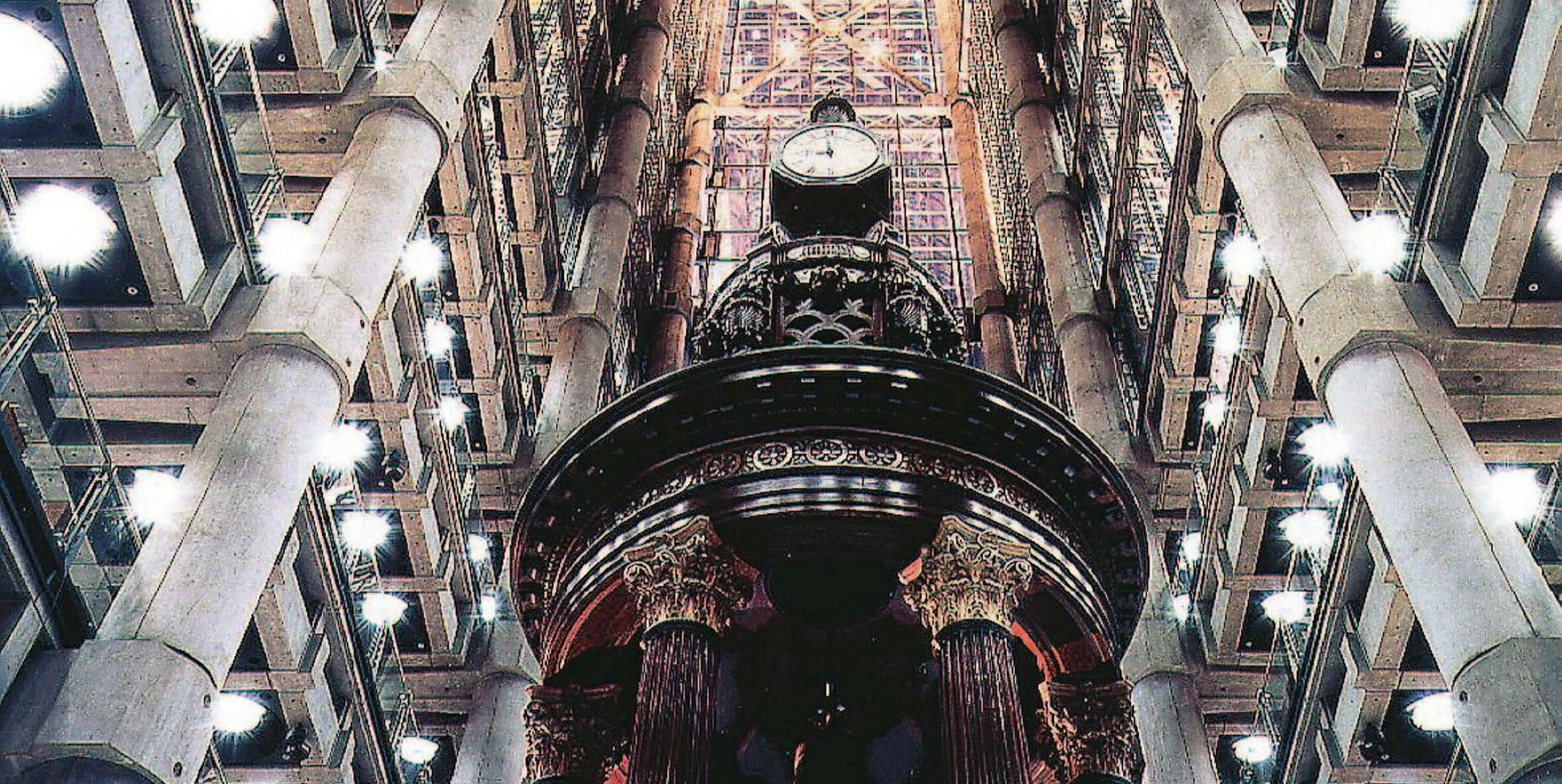

The Lloyd’s of London insurance market and a host of major banks are among those companies that have made public statements regretting their involvement in human trafficking. Lloyd’s has offered financial payments to current BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) projects.

P&O’s name has become embroiled in the controversy, as one of its very early directors, Joseph Christopher Ewart, made a lot of money in compensation for his slave plantation. P&O itself was not believed to have shipped slaves.

Insuring slave vessels on the Africa to Caribbean route generated 6% of UK marine insurance in the last 50 years before the trade was abolished, according to academics at Hull University in England. The value of all slaving is estimated to have accounted for more than 10% of Britain’s GDP by 1800, Klas Ronnback of Gothenburg University told the Financial Times.

History is always being rewritten

Can you rewrite history? Can you apply the norms of today to yesteryear? Can you retrospectively establish who benefited and who lost out? And what of today? Is it fair to say — as trade union Nautilus International does — that the rock-bottom wages paid to some seafarers are a modern version of slavery?

Much of this depends on your own personal politics and outlook. I personally say “yes” to many of these questions.

Certainly, history is always being rewritten — and at any one time mainly reflects the views of power brokers of the day. And yes, it’s fair to pass contemporary judgement on past human iniquities, albeit to make reference to the different social and cultural norms.

Should you deal with the legacy of white privilege — and if so, in a financial way? I think yes to the first — being aware of it is a good starting point. And probably yes to the second, but I would not pretend to know how it should be assessed or dealt with.

And as to whether there is modern “slavery” in shipping, I would argue that a race to the bottom through a global search for ever-cheaper seafaring labour is never the way ahead for a healthy industry.

One place to begin dealing with historic perspectives is in our museums. London’s National Maritime Museum has mounted exhibitions on Britain’s involvement in the slave trade, which began tentatively in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

The monarch lent two of her ships to merchant adventurer John Hawkins in the 1560s.

But her initial reaction to the trade as quoted in the museum’s 2016 “London and the Slave Trade” exhibition was perhaps better judged. She said capturing Africans against their will “would be detestable and call down the vengeance of Heaven upon the undertakers”.

The Cass name is feeling some of that vengeance.