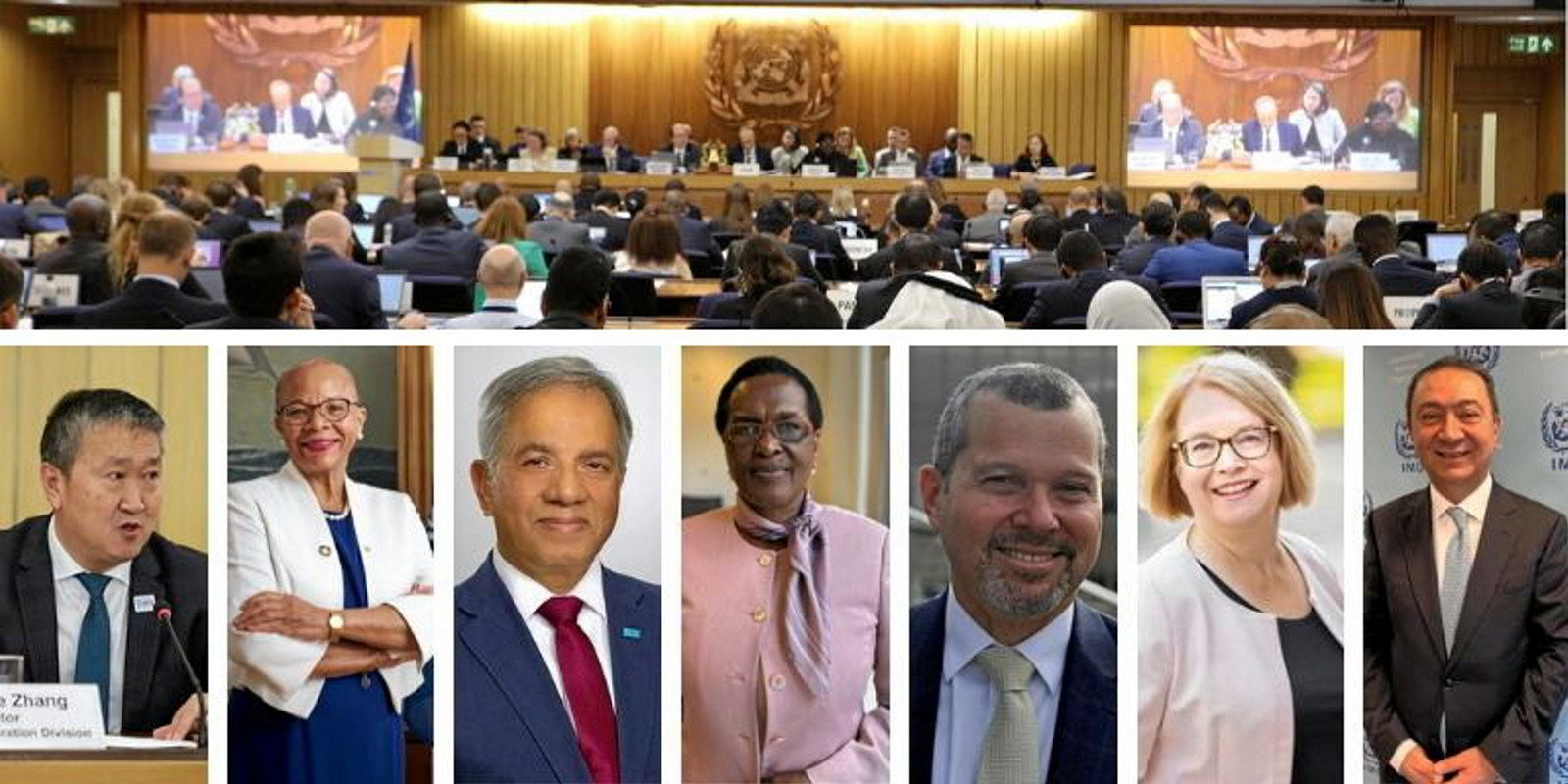

Earlier this month, Panama’s Arsenio Dominguez sat beside Harry Conway as the Liberian chairman of the International Maritime Organization’s Marine Environment Protection Committee announced a historic agreement to target net zero emissions by 2050.

As director of the Marine Environment Division, Dominguez was happy to sit among the leaders soaking up the applause.

He was seen as the key IMO secretariat figure in helping the divergent member states achieve a difficult consensus after a long week of political bickering.

His contribution was further recognised this week when he was elected the IMO’s next secretary-general, replacing Kitack Lim at the start of next year.

The IMO is bound to come under fire again because it was a missed opportunity to elect its first female secretary-general, with three strong candidates standing.

Dominguez’s election seems out of step with the growing number of prominent women among IMO delegates who are playing an increasingly influential role.

But equality concerns were brushed aside. This was a pragmatic vote by member states, and one perhaps motivated by fear.

Decarbonisation is set to be the main issue for the IMO over Dominguez’s likely eight-year tenure. It was the safest option to elect someone who already has a record of success in the field and knows the issues and politics inside out.

The decarbonisation issue could even be critical for the future of the organisation.

At the start of the recent marine environment meeting, the United Nations family appeared ready to turn on its shipping arm.

UN secretary general Antonio Guterres and Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, accused the IMO of dragging its feet over decarbonisation.

The message appeared to be that if the IMO cannot perform on meeting the climate change goals of the Paris Agreement, it cannot be trusted to be shipping’s regulator.

The truth is, shipping has now set decarbonisation goals that are far more ambitious than any other international transport sector. But it is often the first to be targeted by greens and politicians for failing to perform on decarbonisation.

That might seem unfair, but it is part of the challenge the new secretary-general will face.

Dominguez’s task will be to guide the member states to agree on technical and economic measures that will help shipping achieve those ambitious goals.

A global fuel standard is a technical measure that will phase in the use of cleaner fuels and is backed by most member states.

The carbon pricing mechanism — or fuel levy — is still a divisive issue on which developing and developed countries cannot seem to find common ground.

While taking on this challenge, Dominguez may find his connection with the Panamanian ship register is used against him.

That should not be the case, as the role of secretary-general should be independent and Dominguez has promised to be “honest, impartial and decisive”.

As things stand, the Panamanian flag is the world’s largest, but it carries a lot of baggage.

It has drawn criticism from the International Transport Workers’ Federation for being a flag of convenience, while it sits on the grey list in terms of flag state performance under port state control.

It has been associated with registering ships that are operating in the “shadow fleet” involved in trading with Russia and other sanctioned countries.

Providing more regulatory oversight over vessels involved in this trade may also be a key issue for the new leader over the coming years.

Panama has decided to clean up its act, clearing out sub-standard ships from its fleet.

That, along with the growth of Liberia, means Panama is likely to lose its position as the leading flag state — at least on a gross tonnage basis — by the time the latest figures are released next month.

Purging the fleet and improving its safety performance might make Dominguez’s job a little easier.