It has been a glorious start to the year for the LNG sector, with soaring freight rates and an industry virility symbol roaring back to life.

A major shortage of available gas ships has sent spot charter rates for large vessels up to record levels of $350,000 per day.

The price of LNG itself in Asia breached the $20-per-MMBtu mark — almost 10 times the value of natural gas in the US, a key exporting country.

In Australia, another key exporting nation, there was good news from Shell as its giant Prelude floating LNG shipping plant started working again.

The world’s largest floating structure has been out of action for a year due to a series of technical faults and other problems.

The $10bn to $13bn leviathan built by Samsung Heavy Industries was once expected to be the first of many when the idea was first unveiled 10 years ago and excitement around gas had no bounds.

Sober assessments

But reality has since set in with more sober assessments of gas growth coming alongside questions about the cost of such giant structures.

Last year, Shell took a $9bn write-down on its Australian gas assets, including Prelude which is moored off the north-west coast.

Shell took a $9bn write-down on its Australian gas assets, including Prelude which is moored off the north-west coast

Gas demand and prices slumped in 2020 due to Covid-19, with 200 US export cargoes cancelled as the pandemic hit.

Asian LNG prices have more than bounced back in recent weeks and have hit their highest levels since 2014.

A combination of factors has led to this commodity and shipping boom — including cold weather in Asian importing countries, disruptions at production facilities and congestion in the Panama Canal.

The bonanza for the owners and brokers of LNG tonnage is expected to continue next month but will likely slow in March as the weather warms.

Views are mixed as to whether 2021 will be a good or relatively moderate year for the wider gas sector.

Poten & Partners has predicted LNG demand will fall, while Wood Mackenzie and S&P Global Platts Analytics have both cut back growth forecasts.

Jeff Moore, manager of Asian LNG analytics at Platts, said: “We are now expecting the 2020 market to be roughly 364 million mt per year, which is a growth of around 9m mt per year above 2019 levels.”

Unwinding tensions

One of the potential advantages in the short term should be the change of US president, which should lead to a gradual unwinding of the vicious trade war with China.

The Far East country is the fastest-growing LNG importer and a key market for the growing number of US gas exporters.

With the post-Covid-19 Chinese economy coming back to life strongly, there are opportunities for more gas use — and contracts.

Europe remains a different story, with the latest Covid-19 outbreaks and lockdowns dampening demand for gas.

As my colleague Lucy Hine has reported, Mitsui OSK Lines and German energy company Uniper have just slammed the brakes on the Wilhelmshaven gas import terminal project, citing the need for a rethink.

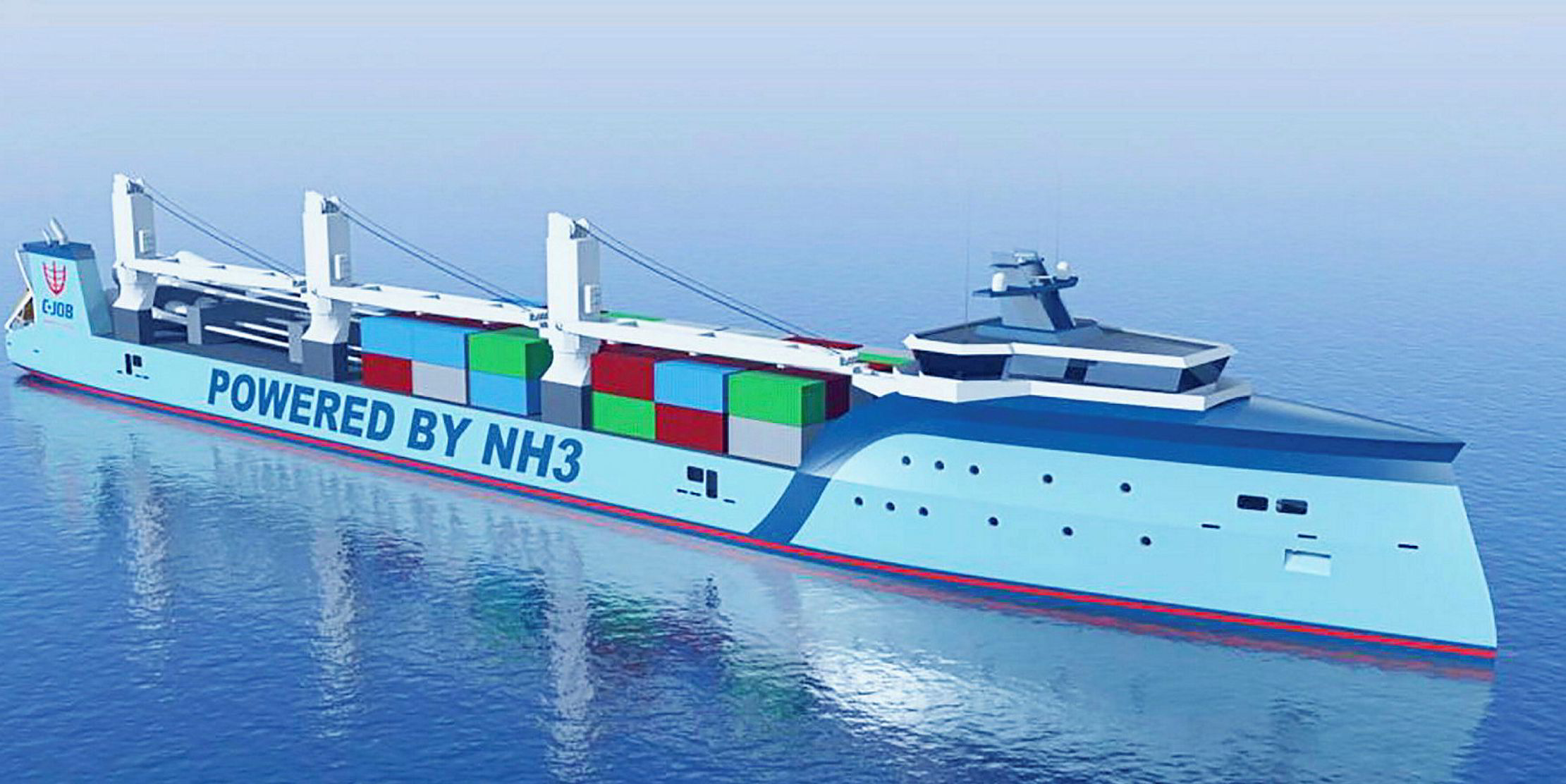

There is also a wider question about the future of gas that is gaining prominence, even as shipowners fret about whether to buy LNG-fuelled vessels or wait for no-carbon fuel cells, ammonia or hydrogen engines to be developed.

Green transition

Enormous growth in gas and LNG demand over the previous decade was built around a switch from coal or other dirtier fuels to gas for power stations generating electricity.

Gas was hailed as the “transition” product to help the world move from fossil fuels to zero-carbon energy sources.

Shipyards in the Far East have been crammed with orders for new gas ships.

But some now argue that there is no place for even lower-carbon fossil fuels such as gas if the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change are to be met.

This partly explains the loud debate around the use of hydrogen for ship engines and should it be “grey” hydrogen made with fossil fuels; or blue, made with fossil fuels but with CO2 being captured and stored; or green, which is derived from renewables?

The long-term future may be visible in Norway, where the government has just announced plans to slap a $240-per-tonne CO2 tax on oil and gas production by 2030.

US President-elect Joe Biden has also talked about a possible carbon tax as part of his $2trn green revolution.

The longer-term future of gas may be somewhat uncertain but what isn’t? For now, LNG shipowners with spot-market tonnage are enjoying an exhilarating ride.