Should ships be built to better withstand the worsening weather conditions the oceans can produce, or the conditions that they are most likely to encounter?

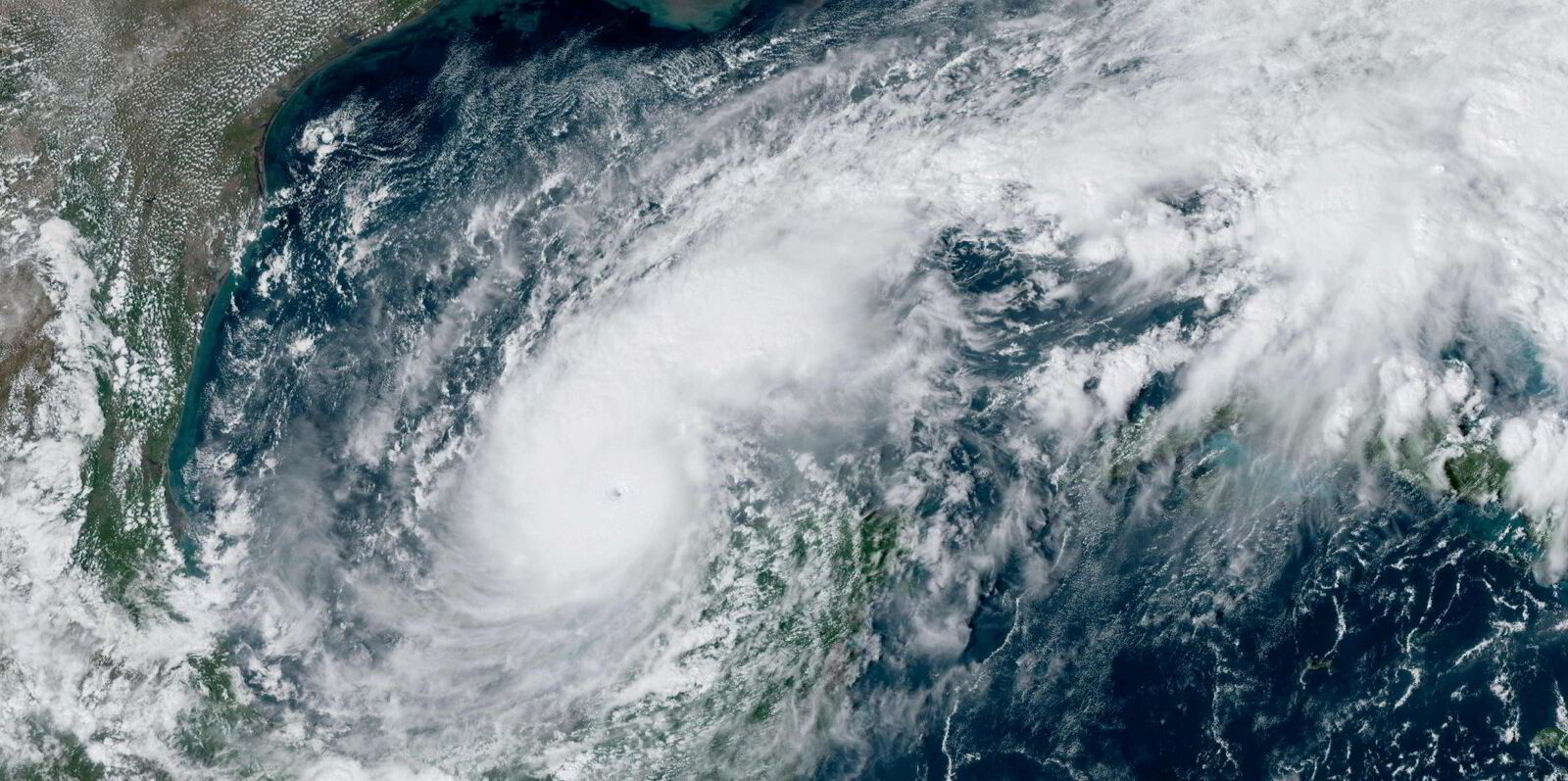

Larger, more frequent storms in the oceans, linked by meteorologists to climate change, have unsurprisingly focused rule-makers’ attention on the ability of ships to deal with these tougher conditions.

The question they are trying to answer is whether ship design should be more robust to handle anything the ocean can throw at a ship.

Or should the design reflect the ability of the ship to use voyage planning and potentially never come near the most rogue of waves or the most perfect storm?

Class societies have long demanded that ships are built according to structural rules, now combined into the common structural rules that all the leading class societies follow.

These rules determine the amount of steel used in a ship, how capable it is to withstand bending moments and twisting, and also the robustness against steel fatigue.

The North Atlantic Ocean is considered the beast of all oceans and is where the most frequent and severest storm conditions are encountered.

The wave heights there are used in calculating designs of ships over 90 metres in length and set for international voyages.

Shipping associations, however, were left scratching their heads last year when a revision of significant wave heights from the International Association of Classification Societies (ICAS) led to a suggestion that data used in safety limit designs could be lower.

Significant wave height is the mean wave height, from trough to crest, of the highest third of the waves measured. So it is not the highest rogue wave in the oceans.

The significant wave height values that the IACS published last year were queried by ship owner groups Intertanko, the International Chamber of Shipping, Intercargo and the Royal Institute of Naval Architects.

In short, IACS argued that the data used for previous calculations used visual wave height observations and lacked robustness, particularly when wave heights exceeded 12 metres.

The ability to measure the Atlantic Ocean’s conditions using satellite data and ocean buoys means there is much more accurate data, IACS said in its response to queries and papers submitted to the International Maritime Organization.

However, the shipping groups said that the accuracy of this data is still evolving.

IACS also used AIS data to track thousands of ship paths across the Atlantic over seven years to get a more accurate idea of which parts of the Atlantic were sailed.

This hindcasting of conditions means voyage routing, weather avoidance and other operational aspects have been taken into account.

Part of the argument is that ships are increasingly weather-routed and avoid the worst storms and weather conditions.

Additionally, the focus area for defining the Atlantic was extended south to better reflect the routing of tonnage, IACS said, something that its critics suggest softens the data as wave heights further south are less extreme.

The data has now been audited by the IMO which has asked IACS to revise its code and offer more explanations so the wave data can be better used by ship designers.

It also wants to see a further revision in the coming years to reflect what is going on with ocean weather conditions.