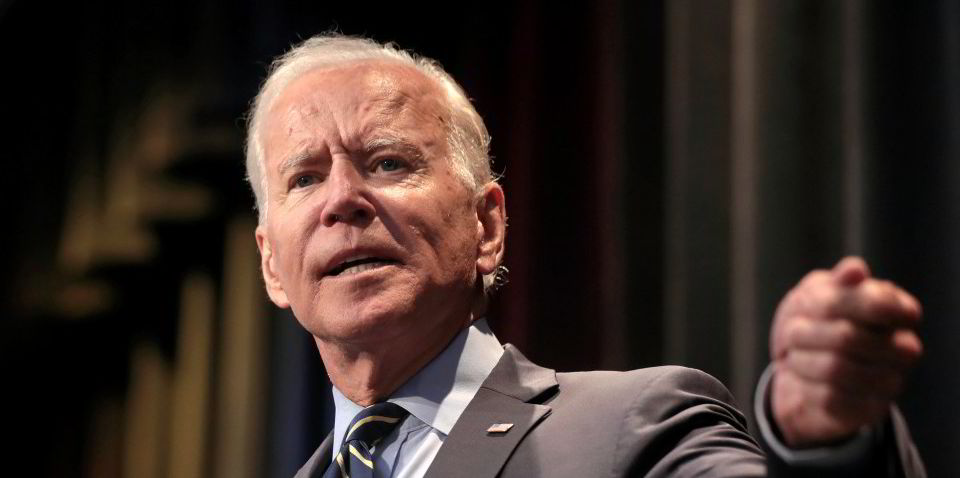

Joe Biden's inauguration as US president is a time for shipping to lobby for policy changes. Ending US unilateral sanctions on international trading should be one of the headline goals for shipping, in partnership with its banking and trading partners.

The political and moral case against sanctions is too familiar to make in detail here.

Trading sanctions are politically ineffective against the intended targets, commercially costly to the countries that impose them, and morally indefensible for the harm they inflict on innocent populations. They are essentially acts of war and should only be imposed in acute crises by an impartial multilateral body, if ever.

Years of experience have demonstrated that point.

What makes it relevant now is the dramatic reversal of political leadership in the US.

A new US administration means it is time to set a new lobbying agenda. Every stakeholder that employs people to influence governments and multilateral bodies — as shipping certainly does — should be making ready now to present its case on the issues that matter to it.

For individual businesses, of course, a change of government in the US is always a time to talk to your lawyer. If you are exposed to shifts in US policy on trade, tax, finance, or environment, you need to know what Joe Biden is likely to do to you or for you. And international law firms have been polishing their crystal balls since the US elections in November, so advice is on offer.

Influencing policy

But for industry bodies and large players that pay to have the ear of policymakers, it is time to influence policy, not just seek advice about it. And as the Biden administration gets underway, shipping should make common cause with banking, industrial cargo interests, labour, and all other stakeholders in international trade to agitate for a multilateralisation of trading sanctions.

The time is especially opportune after the casually brutal Donald Trump approach to foreign policymaking, not least in trading sanctions.

But since long before Trump, the vast majority of transactions in global shipping and trade have been vulnerable to the poorly informed whim of US legislators. US dollar-denominated transactions can only go through if bankers feel safe. And no banker feels safe from the US Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control, better known as Ofac.

At the same time as they are universally feared, US trading sanctions are paradoxically useless against the intended targets

At the same time as they are universally feared, US trading sanctions are paradoxically useless against the intended targets. The best evidence is Cuba, a country whose geography and economy ought to have made it as vulnerable to 60 years of US sanctions as any country could be. Sanctions remain irresistibly attractive to US politicians eager for the votes of the descendants of Cuban refugees in Florida, but Fidel Castro outlived them, and they never brought any supposed enemy of the US to its knees.

The prospect of accidentally doing business with an entity connected with North Korea, Iran, Syria, Venezuela, or Cuba has long been a favourite nightmare of businesspeople who routinely make international fund transfers, but in fact there are some two dozen countries on whose governments, citizens, or corporate entities the US currently imposes different levels of trading sanctions. An entire subspeciality of lawyers has grown up just to keep businesses compliant with the US Treasury's ever-changing and maddeningly inaccurate lists of targets.

Creating the crime

The lawyers are expensive but mostly harmless and often even pleasant people. But another sub-industry that exits and thrives thanks to US sanctions comprises the shipowners and traders who serve the legitimate trading needs of sanctioned countries.

As with any other form of prohibition, it is the penalty that creates the crime. Quality shipowners are not the ones who will be attracted to invest in a fleet of ships that furtively serve sanctioned countries, under flags of countries that do not lose any sleep over the seaworthiness of their national fleets.

The only people who would really lose out by a multilateralisation of shipping sanctions under international treaty would be the compliance lawyers, the shady shipowning niche that serve sanctioned countries, and the journalists who write about them. All of us would find better things to do.