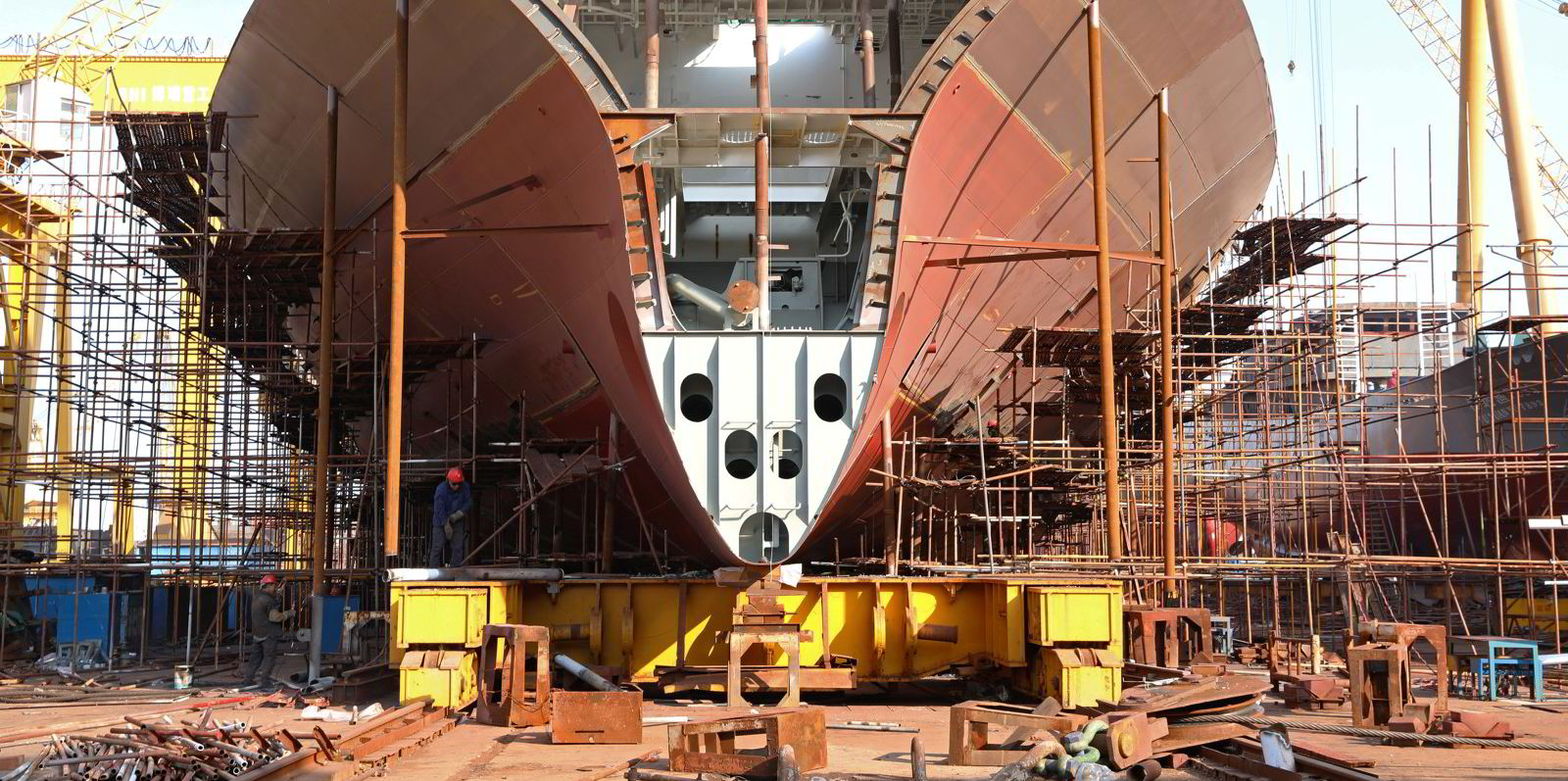

Shipbuilding is back in vogue. From the Far East to the West, governments are keen to highlight their commitment to the industry. The focus comes amid continuing financial troubles for many yards caused by Covid-19 last year contrasting with the tsunami of new orders in 2021.

The bust-to-boom cycle is now triggering a capacity crunch that is disrupting production and driving up prices.

While China is suffering from severe equipment shortages for new vessels, South Korea is helping yards with staffing shortages.

Britain, which once built half the world fleet but now barely constructs commercial vessels, has just set up a National Shipbuilding Office and will shortly unveil a National Shipbuilding Strategy in a bid to make its own comeback.

These moves across the globe are driven by different imperatives but heightened national self-interest, job creation and decarbonisation are all playing a role.

For some time, South Korea has been determined to win back the crown stolen by China as the biggest shipbuilder in the world.

Clarksons Research previously indicated that Seoul could overtake Beijing on new orders by end-2021 but China has just notched up its best seven-month performance — 474 new vessels contracted — since 2008.

Consolidation is still taking place with the planned merger of Hyundai Heavy Industries and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering in South Korea following the tie-up between the two biggest Chinese state firms to create China Shipping Group.

The South Korean merger is currently stalled by a European Commission competition probe.

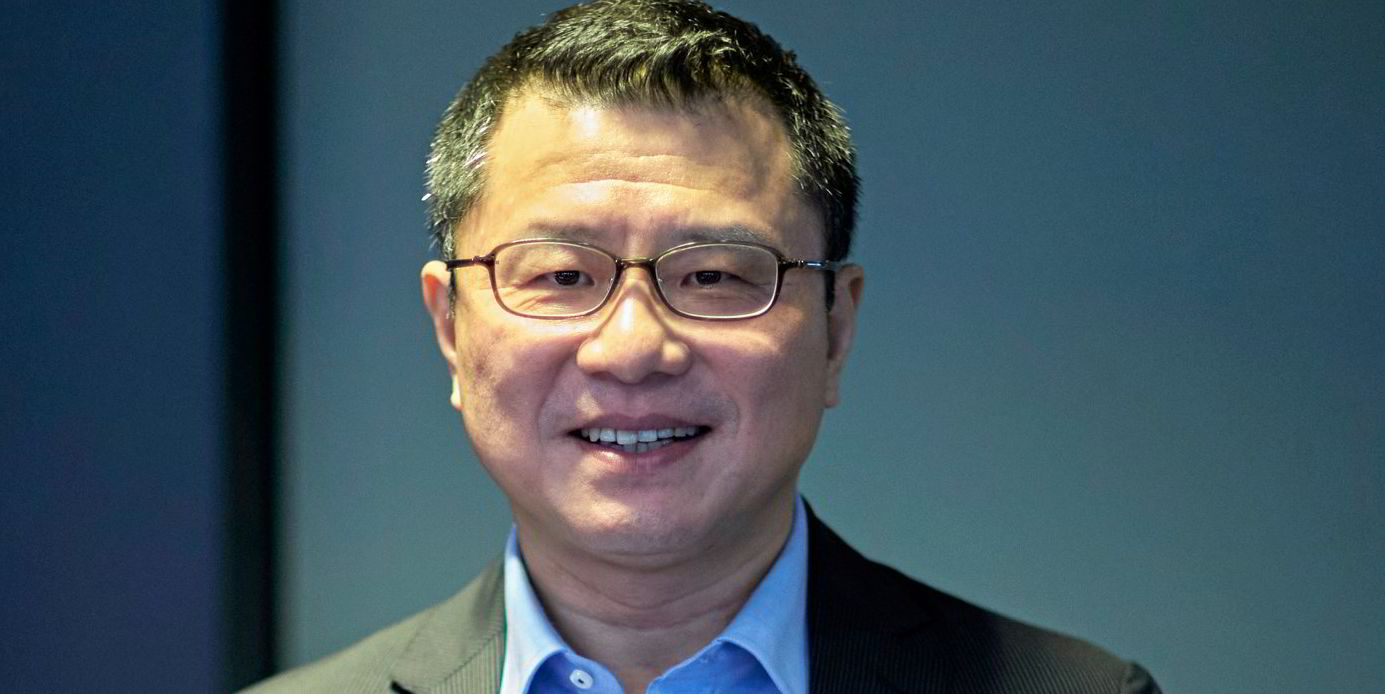

We will strengthen our shipbuilding industry so that we hold the world’s number one spot without contest

South Korean president Moon Jae-in

South Korean President Moon Jae-in earlier this month outlined his “K-ship” strategy on a visit to Samsung Heavy Industries’ yard at Geoje.

The K-ship strategy

He announced that central and local government will offer KRW 1m ($856) per month to shipbuilders for each new employee they hire.

Other public subsidies will be provided for retired shipyard workers to be lured back into the workplace.

New working visa arrangements are to be given to foreign welders and other skilled staff, while research and development support will be given to build a new generation of “green” vessels.

“Shipbuilding has been one of our main industries which has contributed so much,” Moon was reported to have said by Korea JoongAng Daily.

“But because of the stagnation in the global ship market, our companies, workers and local economies had to struggle. Through our strategies, we will strengthen our shipbuilding industry so that we hold the world’s number one spot without contest.”

SHI itself has won a whole spate of new containership and LNG carrier orders in 2021 but has not made a profit in six years.

It posted a KRW 1.54 trn loss last year and analysts expect a deficit — although much smaller — in 2021 even as it cuts costs.

SHI is currently in the middle of an acrimonious industrial dispute with local workers over the closure of its Ningbo yard in eastern China.

But China’s main worry currently is not so much winning new orders as fulfilling its existing cascade of container and dry bulk ship contracts.

Equipment manufacturers in that country have been caught out by the sudden burst of post-pandemic workload.

This has caused shortages of crankshaft and other engine parts, leaving shipyards reluctant to take on new orders.

China’s engine-building capacity was severely pruned after the 2008 financial crash, with some companies closing while others scaled back.

To add to these problems there has been a forced closure of steel-making capacity to reduce carbon emissions.

This contraction has helped ramp up steel plate costs and led to wider inflation of shipbuilding contract prices.

Added to this are widespread power shortages that have halted output at Chinese plants making parts for Apple computers and Tesla cars. Morgan Stanley analysts estimate 29% of cement makers have been hit as well as remaining steel producers, the latter putting a brake on iron ore shipments.

Spooking stock markets

All of this has unnerved stock markets and raised wider questions about the country’s future growth levels.

Fears of collapse at real estate giant Evergrande and clampdowns on tech companies have also unnerved global investors, as TradeWinds noted last week.

The power supply shock in the world’s second-biggest economy and largest manufacturing centre could knock 1% off China’s GDP growth in the fourth quarter, analysts at investment bank Morgan Stanley warned.

Shipyards have been struggling for over a decade but they are back in the sun now. It could even be too hot.