The 11th annual Deep Sea Mining Summit in London this week again raised the banner for the ocean mining of vital minerals needed more than ever for the energy transition and the electrification of the global economy.

“Deep sea mining together with shale oil is the most interesting growth industry of the next 25 years,” said a rolling banner headline on the conference website. Another claimed the “deepsea gold rush is a game changer: deepsea mining is close to a breakthrough”.

Since Jules Verne wrote Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea more than 150 years ago, the world has been captivated by the potential and mysteries of the seabed in much the same way that science fiction sent imaginations wild over interplanetary space travel.

And for more than 50 years, there has been particular interest in the mineral opportunities sitting in abundance at the bottom of the ocean, but this has never turned into the future industry that many people — not least conference organisers — dreamed about.

But could it now be different? The atmosphere is definitely hotting up, with big names moving into the sector from the world of shipping and beyond.

The United Nations-backed International Seabed Authority (ISA) might consider the first commercial seabed mining production application in the coming weeks due to pressure from the Pacific Republic of Nauru on behalf of Canada’s The Metals Co (TMC).

The group’s investors include liner giant AP Moller-Maersk and commodities group Glencore, and the business would like to start commercial operations next year if it can.

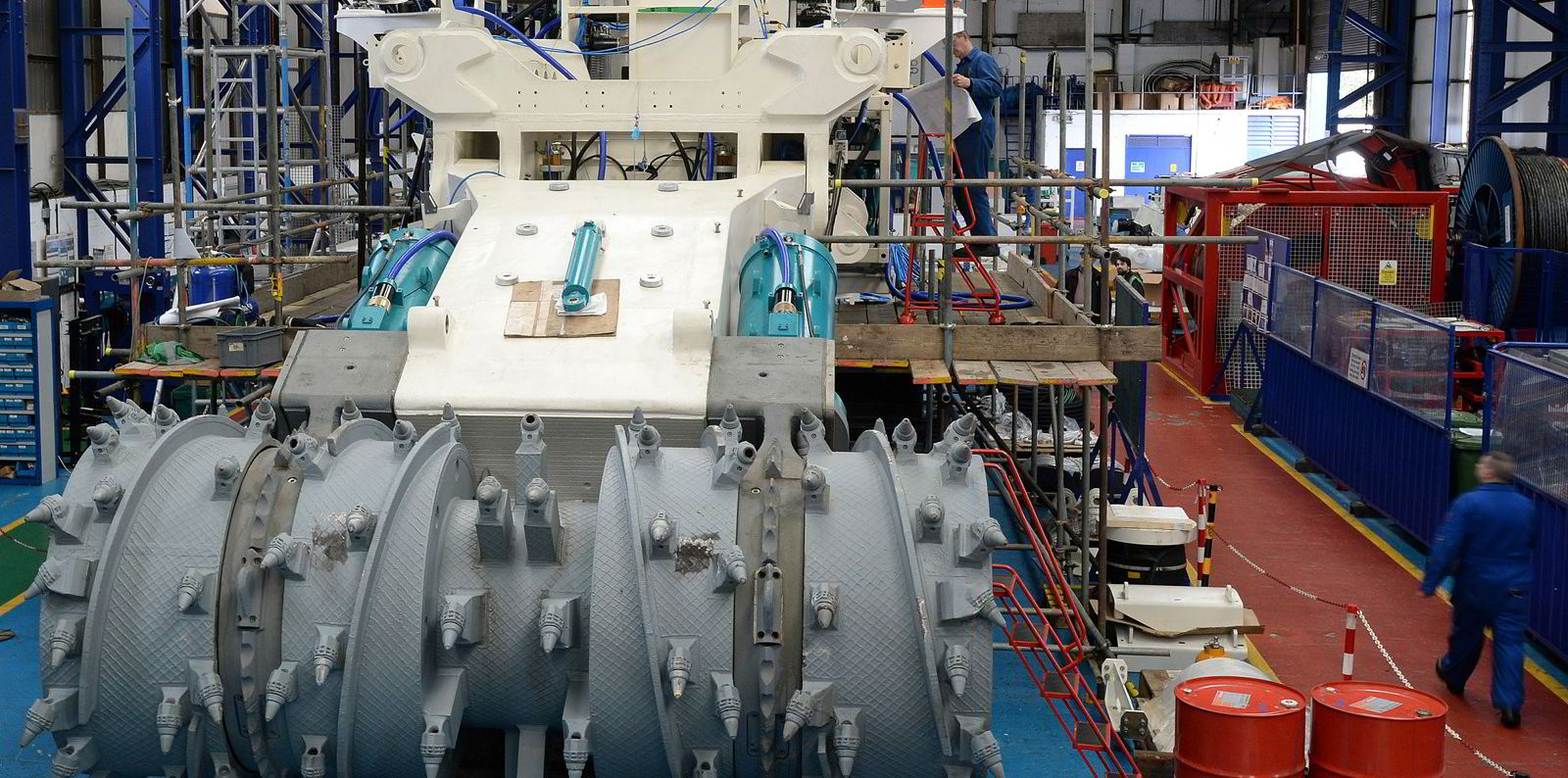

Last November, TMC contractor and investor Allseas Group declared “hundreds of thousands of mineral-rich polymetallic nodules” had been extracted from the seabed and loaded onto its 60,330-gt converted drillship Hidden Gem (built 2020) from the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean.

Allseas said that under its pilot collection trial, the nodules came from 4.3 km (2.7 miles) below the water surface in what it claimed was the first “integrated system test” in the area since the 1970s.

Last spring, the world’s largest offshore drilling contractor, Transocean, announced it had bought a stake in Ocean Minerals, a company that holds a licence to mine seabed minerals off the Cook Islands in the Pacific.

In February 2023, Transocean invested in Global Sea Mineral Resources, a subsidiary of Belgian group DEME, which holds seabed mining licences. Transocean plans to convert the 59,000-gt drillship Ocean Rig Olympia (built 2011) for seabed mining work.

And in March, Norway’s Loke Marine Minerals bought UK Seabed Resources with its Pacific Ocean licences, in a move supported by the Wilhelmsen shipping group as well as Norwegian defence contractor Kongsberg and UK offshore engineer TechnipFMC.

Few people deny that more minerals are needed for everything from mobile phones to electric car batteries that are now integral parts of modern life and that support efforts to decarbonise economies to tackle the climate crisis.

Cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese and rare earth metals are all potentially to be found in the deepsea polymetallic nodules now under scrutiny.

Deepsea sources are seen as a geopolitical safety valve to those worried that China and Russia have an outsize grasp on land-based supplies.

But environmental concerns are also rising about the negative impacts on nature and communities from onshore mining, and the Allseas offshore move did not go unnoticed by environmentalists. Greenpeace monitored the event and claimed that the discharge of waste into the sea surrounding the operation is inherently polluting.

The conference in London this week was met with a planned protest from the Ocean Rebellion group and ear-splitting sound from a specially formed heavy metal band, the Polymetallic Nodules, in a symbolic act to highlight how drilling noise might disrupt ocean wildlife.

It is not just eco-activists who have qualms about deepsea mining. France, Germany, New Zealand and Costa Rica are among those calling on ISA secretary general Michael Lodge for a “precautionary pause” or a ban on deepsea mining until more research is done on its environmental impact.

Lodge insists he is aware of the need to balance commercial considerations with welfare for ecology and, for the moment, the green light to proceed with mining production will only be given if countries can reach a consensus. For now, only exploration activities will be permitted: the deepsea gold rush is still on hold.