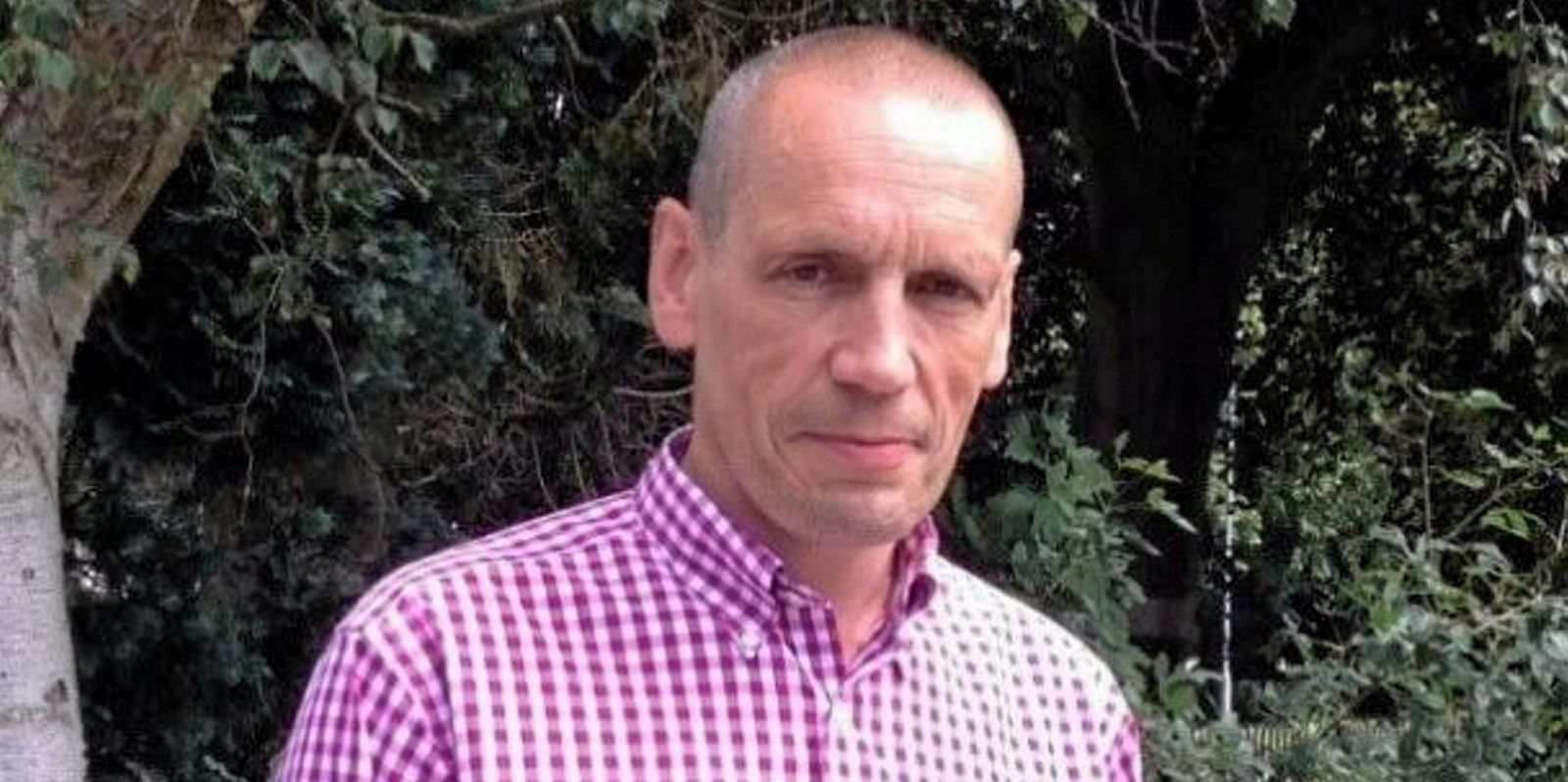

The Mission to Seafarers Singapore ship visitor Alexander Choy climbs the steep gangway of a large container ship at bustling Pasir Panjang port. It is the fifth gangway he has climbed on this hot, humid day, with more ahead.

Any fatigue dissipates as he is met by the eager faces of the vessel’s crew at the gangway’s end. For many, this brief stopover in the Asian city-state offers less than 10 hours ashore.

These seafarers, often facing loneliness and isolation, may see Choy and his colleagues’ smiling faces as their only fresh interaction until their ship reaches their next discharge port.

Now, more than ever, seafarers need friendly faces after unprecedented job pressures, stress and isolation heightened by geopolitical tensions and climate concerns.

There is increasing worry about the mental health of seafarers and a growing focus on creating safer environments for them.

As reported by TradeWinds, statistics from the International Association for Suicide Prevention indicate that more than 25% of seafarers suffer severe depression and almost 6% of deaths at sea are suicide.

Obesity, mental health problems and gender discrimination are issues laid bare in the Mission’s recent Seafarer Happiness Index.

Boredom and stress caused by a shortage of onboard facilities, a lack of shore leave or access to reliable wifi are among common complaints. This is where the Mission steps in — as it has for over a century — to give seafarers access to the support they may not have at sea.

The eyes and ears

That support stretches to justice and welfare needs, including employment issues such as problems over pay, contracts or physical abuse while on board. Ship visitors act as the seafarers’ eyes and ears, checking information and referring crew to the relevant authorities where needed.

Spiritual needs are tended to on request, with the Mission conducting prayers, services and funerals.

Increasingly crucial is its response to well-being concerns, offering seafarers non-judgmental human contact.

Staff in Singapore have reported a rising number of individuals grappling with mental health challenges, resulting in cases of self-harm and, tragically, suicide.

Ship visitors are a trusted listening ear for seafarers sharing concerns over feelings of isolation and loneliness when away from families and the wider world for long periods.

Seafarers are encouraged to enrol in programmes designed to help them and their families deepen their understanding of their needs, increase awareness of mental health issues and explore ways to support each other.

Responsible communication, time and financial management, self-care and suicide prevention are all on the agenda.

Human touch

TradeWinds joined the Mission’s Singapore ship visitors for a day to discover how it all works.

Seafarers greeted us enthusiastically, eager for the fresh faces and new conversations that offered a break from their usual onboard interactions.

Visiting one Greek-owned feeder container ship, the bubbly, chatty crew were keen to lay on hospitality, even providing an afternoon snack. Laughter and smiles were shared as they talked about their fellow companions and lives outside shipping.

Although a Christian charity, Tan Soon Kok, the Mission’s port chaplain in Singapore, said its services are open to all regardless of race, nationality or religion.

Tan shared his experience of calling on a Hindu priest at the request of the captain to conduct a funeral for a deceased Hindu seafarer.

Catering to women seafarers, Susan Koh, administration manager of the Mission in Singapore, also doubles as a ship visitor. Providing a safe space ensures women seafarers feel welcome in the male-dominated world of shipping.

The visitors average around 10 vessel visits per day, sharing the Mission’s services such as portable internet routers that seafarers can borrow during their dockside stays.

But perhaps most importantly they check the pulse of life on board, speaking to seafarers and the captain where possible.

All in a day’s work

Choy recalls revisiting one ship that had been hit by a rocket after passing by the Red Sea. Seafarers had had to manually put out the fires.

Choy said the event had strained their mental health.

He said he would make it a point to revisit the ship once it arrives in Singapore waters to reconnect with the seafarers and check on their well-being.

Choy also talked about the recent oil spills in Singapore waters and how there has been a new generation of workers since past incidents.

He said: “The topic of the day is oil spills. Have we lost touch with how to clean up oil spills despite the oil spills we had in the past in Singapore?”

The Mission also tries to provide the same level of support to seafarers on board vessels in Singapore’s anchorages. Motor launches are hired for visits to ensure seafarers do not feel neglected.

A day’s work for a ship visitor also includes transporting seafarers around the port. There are two drop-off points, the International Drop-In Centre and the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority office, located at the port.

“This service is highly sought-after as time ashore is always precious and often not enough,” said Tan.

Welcome centres

Located in more than 200 ports in 50 countries, the charity’s International Drop-In Centres provide seafarers with safe social spaces with free wifi, drinks and snacks, games, books and clothing.

For seafarers unable to venture beyond the port gates but who want mementoes for friends or family, souvenirs are also on sale.

In the neutral, non-work environment, the seafarers’ carefree nature was noticeable. They talked openly, socialised freely and planned a place to visit outside the port.

Choy said he finds it meaningful and rewarding to connect with the seafarers and learn more about their stories.

While shipping patterns and the needs of seafarers have changed dramatically over recent decades, as has the work of the Mission, the goal remains the same: to look after the well-being of seafarers.

The Mission was founded in 1856. It branched out to Singapore in 1924 and will be celebrating its 100th anniversary next year.

“We were relevant to seafarers 160 years ago and still are, and we pray we will continue to be relevant to seafarers in years to come,” said Tan.