Walking towards the International Transport Workers’ Federation headquarters in London, you can’t help but notice that it resembles a bus depot.

Half-a-dozen red buses are lined up outside the building along a busy tree-lined street, which is not the most convenient place to have buses terminate.

Mark Dearn, the ITF’s maritime communications manager, explains: “It’s a bus stand outside and we welcome London bus drivers into our building to make themselves a cup of tea or coffee and use the toilet in between their journeys.

“It makes it a more interesting office, as you never know who you will run into — and it’s definitely motivational to be bumping into the transport workers we work to support every day.”

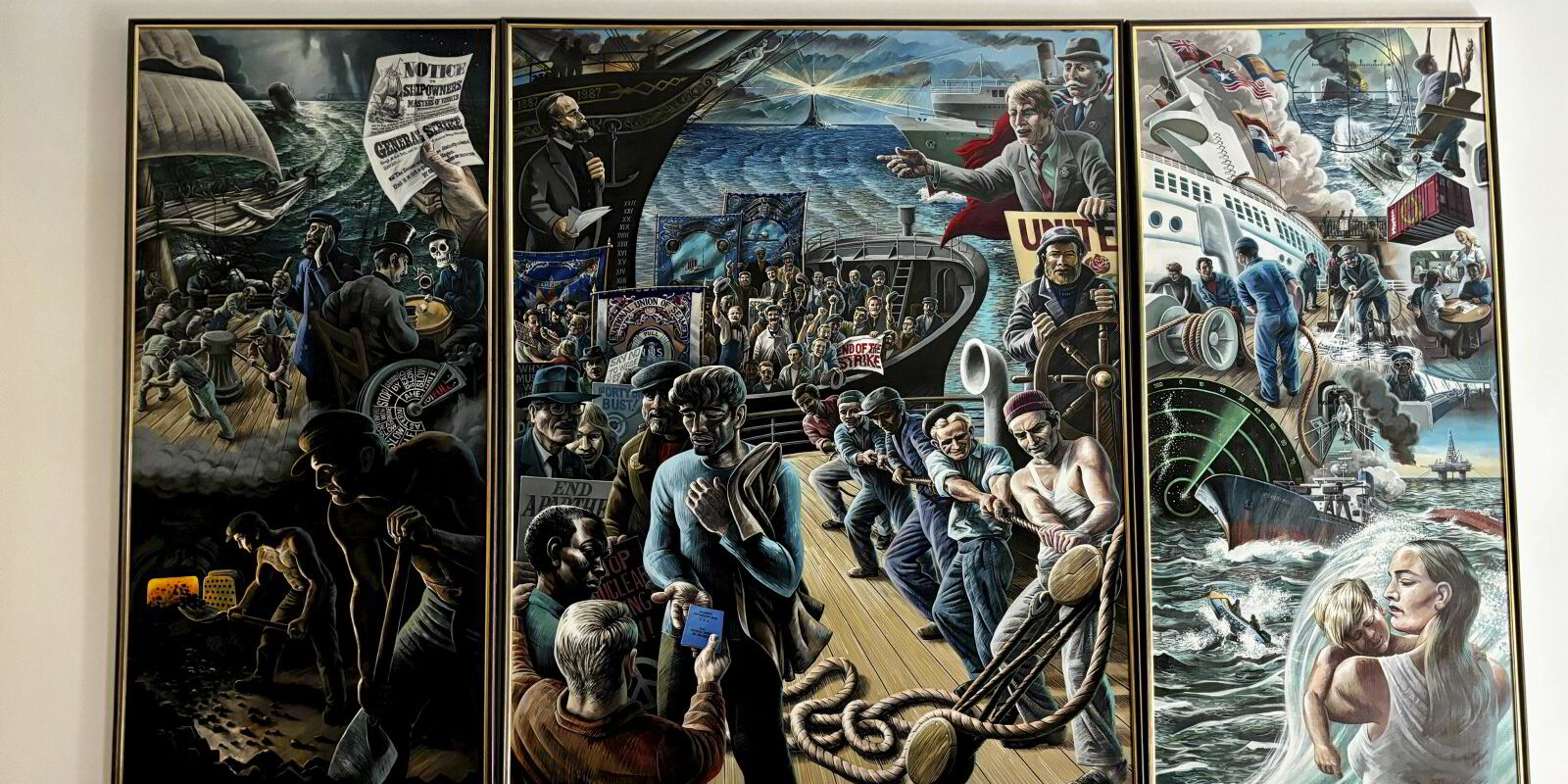

The lobby is dominated by an impressive Diego Rivera-esque mural depicting the evolution of dramatic events in the National Union of Seamen’s history.

Painted by Mick Jones (son of legendary trade union leader Jack Jones), the work is dedicated to the ratings of the British Merchant Navy, and was presented to the ITF by the UK National Union of Rail, Maritime & Transport Workers.

It soon becomes clear that this is not your usual office; rather, it is a cultural hub that holds its members and heritage close to its heart.

The ITF was founded in 1896 at a meeting in London organised by Havelock Wilson, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and Charles Lindley. Initially called the International Federation of Ship, Dock & River Workers, it was renamed after absorbing the International Commission for Railwaymen in 1898.

It represents 16.5m workers from more than 700 affiliated unions in 153 countries in all industrial transport sectors: civil aviation, dockers, inland navigation, seafarers, road transport, railways, fisheries, urban transport and tourism.

However, it is the dockers to whom the ITF — and many other labour unions — are most indebted. “They’re the ones that spearheaded everything for the ITF and British trade unions generally,” Dearn explained. “They are among our trade union superheroes.”

In 1889, 100,000 dock workers in the Port of London came together to strike for better pay, and won a claim of sixpence per hour.

This historic industrial action helped establish strong trade unions among London dockers and is considered to have paved the way for the development of the British labour movement.

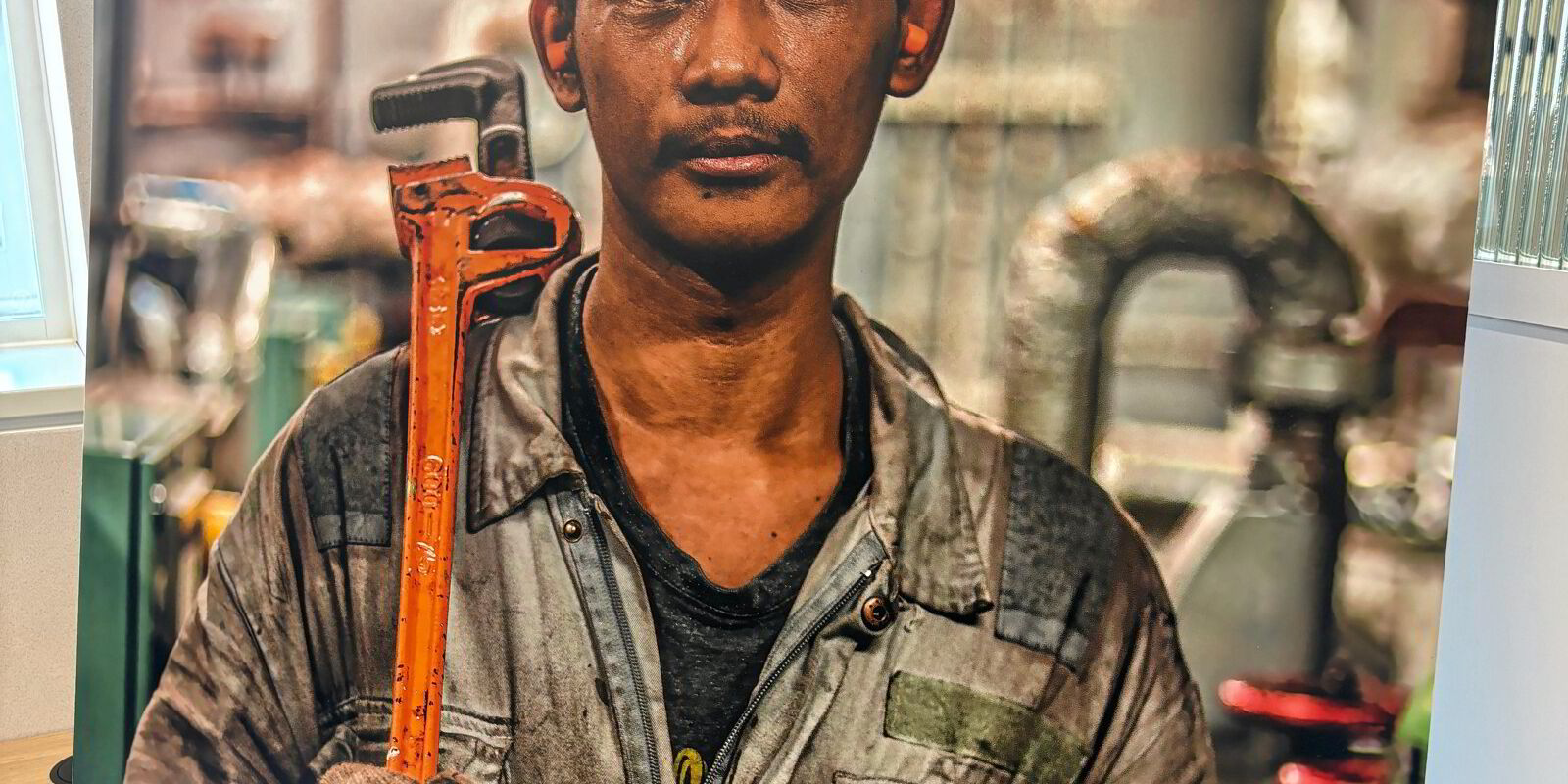

Behind the portrait above lies a story familiar to seafarers the world over.

The image, taken by Aljon Manlangit of his Filipino colleague, wiper Wendell Pineda, during the pandemic in 2021, won the second ITF Seafarers’ Trust photograph competition.

Manlangit said that following his first contract as an engine boy, Pineda returned to sea after less than three weeks back in the Philippines, which he had to spend in quarantine.

“Without reaching home and even without seeing his partner and their two-year-old daughter, Mr Pineda embarked again as an urgent request of his shipping company,” Manlangit said.

“Somehow, embarking a ship for a second time coming from a short break did not give Mr Pineda a sad thought but instead [he] considered himself lucky, for he will embark again and earn money to help his family...

“Mr Pineda’s story is not just about his own self-experience, but the face and story of most of us seafarers, especially the fathers, that even if Papa is tired, Papa will never give up.”

To this day, Dearn said, dockers are at the core of the ITF’s work and are still action-oriented members who “fight to get things done”.

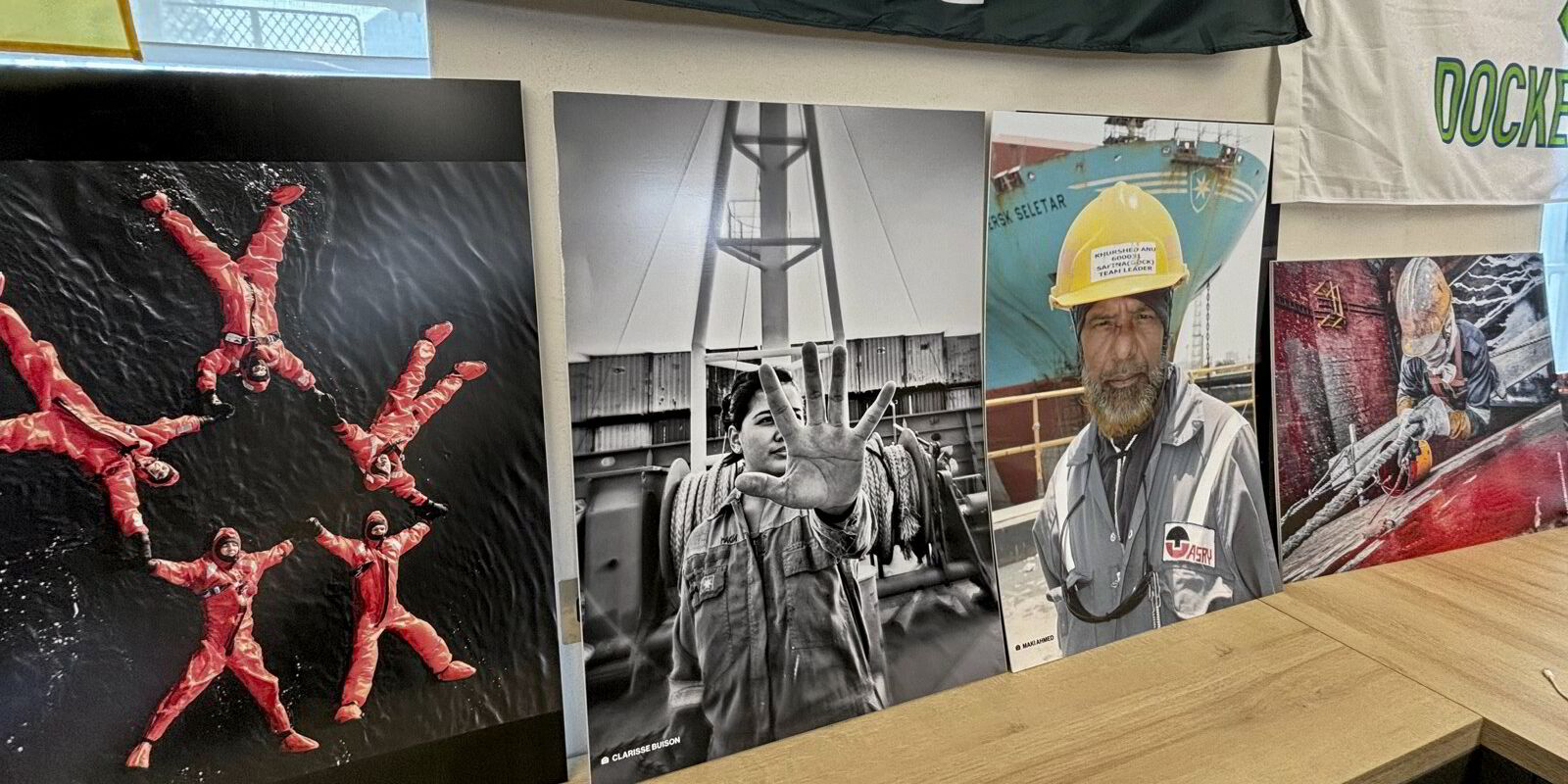

Some of these “superhero” dockers and other transport workers from around the world, particularly seafarers, can be seen in the ITF’s regular photography competition, with examples exhibited throughout the building. Again, keeping its members at its core as well as celebrating them.

Diverse flags and banners also adorn the hallways and office space, ranging from the Maritime Union of Australia to the Antwerp dockers’ youth movement.

A more corporate feel is offered by the ITF’s United Nations-style conference centre with its inbuilt translator booths and time-zoned clocks.

Dearn said meetings in the room involve unions from around the world and are a fundamental part of how global union federations generally have to operate: “The room is vital to our work joining together transport worker unions around the world from across land, sea and air sections.”

In June, the conference room hosted the Ukraine Maritime Forum run by the Marine Transport Workers’ Trade Union of Ukraine, including officials from the International Maritime Organization.

IMO secretary general Arsenio Dominguez expressed his strong support for all seafarers, including those from Ukraine during the event. “Without seafarers, there is no shipping, there is no shopping,” he said. “I urge everyone to join our campaign to support seafarers and recognise their indispensable role in our daily lives.”

A website championing Ukrainian mariners was launched at the event. ITF general secretary Stephen Cotton said: “Our support goes out to all our friends in Ukraine who have shown incredible bravery. The contribution of Ukrainian seafarers deserves our respect and recognition.”

Seafarer abandonment is another topic that the federation deals with heavily. Mohamed Arrachedi, the ITF’s Arab World and Iran network coordinator, has described abandonment as “the cancer of the shipping industry”.

In January, the ITF reported 132 abandonments for 2023, and the consensus is that numbers are likely to rise this year.

“It remains a major cause for concern and is increasing, unfortunately,” said Dearn. “Although, due to improvements in awareness among seafarers and the technology that enables them to contact the ITF, we are able to report more cases now than we used to.”

On leaving the building, the familiar model ship, a common feature in maritime-themed offices, caught the eye.

“It’s our ship, actually. Well, it was our ship,” said Dearn. “It sank, which is a real shame, as it would have been wonderful to still have it in use.”

The 12,778-gt Global Mariner, built in England in 1979, was the ITF’s floating museum, which sailed around the world. However, it sank in 2000 in the Orinoco River in Venezuela after a collision with a container ship.

Although this might be seen as a bad omen, the ITF displays it proudly, clearly still in tune with its history, although keen to keep looking forward.