When the US issues sanctions against the Houthis for their menacing of shipping, there is one name that is mentioned more than any other.

And it’s a name that the US Treasury Department also frequently cites when it targets the dark fleet of tankers carrying Iranian oil.

That name is Sa’id al-Jamal.

He is accused of being a Houthi financial facilitator who funds the Yemen-based militant group by running an illicit shipping and trading network that has allegedly raised millions of dollars from selling Tehran’s oil and gas.

But that is just a part of a staggering operation that stretches from Turkey to Djibouti.

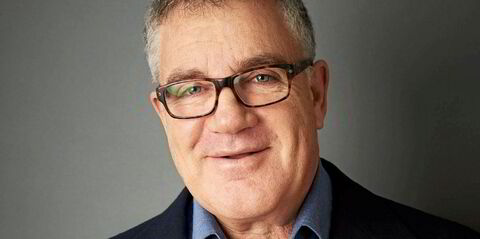

Guled Ahmed, a non-resident scholar for Washington DC think tank Middle East Institute, estimates al-Jamal’s total business network, including an often-overlooked foothold in the Horn of Africa, could generate $4bn in annual revenue.

He said that represents 22% of Yemen’s GDP. “This is a conservative estimate,” Ahmed added.

A recent report by a United Nations Security Council panel of experts on Yemen described al-Jamal’s operation as one of many networks operating from Djibouti, Turkey, Iraq and Iran to provide foreign funding sources for the Houthis.

Substantial funds

“A substantial amount of money is being illegally transferred under the direction of Sa’id al-Jamal, allegedly affiliated with Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force, to support the Houthis,” the panel said.

Al-Jamal’s role in moving Iran’s oil shipments makes him a major charterer of dark fleet tonnage on the opaque trade with China, whose small “teapot” refiners have become the main market for Tehran’s oil.

Ahmed said the Yemeni’s network is also involved in a lesser-known revenue stream — collecting ransoms from shipping companies willing to pay to pass through the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea safely.

Man of many names

There is little publicly available information on who al-Jamal is.

According to the database of the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (Ofac), al-Jamal is a Yemeni national.

He holds a Yemeni passport and is believed to carry two Iranian passports. US officials believe he may have been born in January 1979, or possibly in July 1978. He is believed to be based in Iran.

And he goes by many names. His birth name is Sa’id Ahmad Muhammad Al-Jamal, but he is also known to go by other spellings of that name. He also is believed to have used Abu-Ahmad and Hisham. In some circles, he even uses the alias Caihong, which is the Chinese word for rainbow, according to Ofac.

The US Treasury Department first mentioned al-Jamal publicly in June 2021, when it declared him a terrorist and accused him of operating a network of front companies and vessels smuggling Iranian fuel — which at the time was moving to nations in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

US officials have accused al-Jamal of being backed by the Quds Force, an elite unit of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps that is responsible for overseas operations. Among the Quds Force’s roles is providing support for Tehran’s proxies, such as the Houthis.

Treasury has claimed revenue from al-Jamal’s network helps finance the Houthis’ attacks on shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, as well as providing funding for the Quds Force.

And they have accused him of employing an “expansive network” to help hide the origin of cargoes, forge shipping documents and provide services to sanctioned vessels.

Close associates

Al-Jamal’s partners include his Yemen-based nephew, Abdallah Najib Ahmad al-Jamal, whom Treasury has accused of managing the network’s money laundering operation that uses exchange houses to move cash.

Another family member, Khaled Yahya Rageh Alodhari, was accused of working with al-Jamal to set up a money exchange — Davos Exchange and Remittances.

US authorities have accused Turkey-based Abdi Nasir Ali Mahamud of using his network of businesses as a cover for al-Jamal’s activities.

He was slapped on a sanctions list in 2021, for example, for using his position as managing director of Adoon General Trading to facilitate cash transfers.

His name has continued to come up in Treasury sanctions announcements, with the latest mention in October.

Described by US officials as a “key business partner” of al-Jamal, Mahamud has been accused of being a financial facilitator and a coordinator of petrochemicals smuggling for the network.

Shipowners and operators

US officials have claimed that al-Jamal’s network relies on shipping companies and their vessels, as well as facilitators, to move oil, petroleum products and LPG.

TradeWinds recently reported how Iranian oil is making its way to their main market — independent teapot refiners in China — by relying on a dark fleet of tankers to carry barrels first from the Middle East to the Riau Islands off Singapore and Malaysia.

Cargoes are then transferred to other vessels that carry them to China — all with location transponders turned off.

Al-Jamal’s network is accused of being a frequent customer of such tankers.

At least 33 ships have been sanctioned for activity related to al-Jamal’s network, although some of them were named, in addition to those used by the alleged Houthi financier, because they were controlled by sanctioned shipowners and managers.

Agents and traders

Al-Jamal’s network is accused of using shipping agents that help secure forged documents to show that Iranian oil is instead Malaysian.

US officials have also accused al-Jamal’s network of using under-the-radar trading houses, often in the United Arab Emirates, to help arrange shipments or to facilitate payments.

Shipbrokers and managers in India and Indonesia have helped the network move cargoes.

Since 2021, Treasury has accused al-Jamal of directing revenue through a complex network of intermediaries and exchange houses that funnelled it to the Houthis, including those controlled in Lebanon by businessman Bilal Hudroj, a Turkish jewellery store that doubles as an exchange house, and even an outfit controlled by the head of the Currency Exchangers Association in Sanaa, Yemen.

And al-Jamal’s network has used “seemingly innocuous” companies to facilitate the trade, such as Ascent General Insurance, which was sanctioned in July, to provide cover for vessels, according to Ofac.

Syrian partners

The funds have benefited more than the Houthis. Some revenue from al-Jamal’s network allegedly made its way to Hezbollah, a militant group in Lebanon that is also backed by Iran.

In 2021, Treasury accused Syrian shipping magnate Abdul Jalil Mallah, who was based in Greece at the time, of supporting al-Jamal’s network.

Then in September of this year, Ofac targeted his brother, Luay al-Mallah, accusing him of facilitating trade between Syria and Iran in support of Hezbollah.

In its most recent mention of al-Jamal, last week Treasury expanded sanctions against another Syrian business, the conglomerate Al-Qatirji Co.

Former company leader Muhammad Al-Qatirji, whose surname is also spelled Al-Qaterji, has been on Ofac’s sanctions list since 2018.

In July of this year, he died when a missile hit his car in Damascus. It is believed to have been an Israeli airstrike.

Other family members have allegedly stepped in to fill the breach, including new leader Hussam Bin Ahmed Rushdi Al-Qatirji.

Since the late leader’s death, they directly met Quds Force officials and al-Jamal, Ofac said.

Treasury sanctioned 12 of the company’s tankers for bankrolling the Houthis and the Quds Force through the sale of Iranian oil to Syria and China, as TradeWinds reported.

Somalia and Djibouti network

The Middle East Institute’s Ahmed said the most overlooked part of the al-Jamal network is in the Horn of Africa, where it is active in Somalia and Djibouti.

The researcher, who is originally from Somalia, said the group has connections to al-Shabaab, an Islamic terrorist group in the country that is backed by Iran.

For example, using al-Shabaab facilitators, al-Jamal’s network has a mining operation that is exporting 38 tonnes per year of gold and rare-earth minerals mined near the border between Somalia’s Somaliland and Puntland regions. And the al-Jamal network is involved in the region’s weapons trade supplying the Houthis, he said.

The UN Security Council Panel of Experts has estimated that shipping companies have been paying $180m per month to the Houthis to secure safe passage through the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, although some have challenged the figure as exaggerated.

Ahmed said the al-Jamal network is involved in that, for example, by using its trader network to monitor vessels and in collecting the cash.

And al-Shabaab facilitators work with pirates to track ships and extort from them. Ahmed estimates that the Somali group brings in $20m of cash each month, or some $240m per year.

Djibouti serves as a shipping hub for the al-Jamal network.

Ahmed has pointed out that the country has refused to condemn the Houthi attacks on shipping, and foreign minister Mohammed Ali Youssouf has even defended them as legitimate defence of Palestinians in Gaza.

“Djibouti is what I call the devil in the Bab al-Mandeb,” Ahmed said.

What should be done?

The researcher told TradeWinds that there are two options for dealing with the Houthis as al-Jamal’s network and Iran’s influence spread deeper into the Horn of Africa.

One is “surrendering” by paying ransom, which is what is already happening.

The other is to do what the US did in the late 1700s and early 1800s, when Barbary pirates were attacking US ships.

President George Washington ordered the construction of a fleet of frigates, and then successor presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison went to war against the Barbary States.

“If Trump comes and says, ‘We can take them out’, just as we had almost done, and Saudis are given anti-drone [systems] like the defence system the United States gave to Israel … then these guys can be taken out,” Ahmed said. “It’s the George Washington approach.”

He also suggested addressing the roles of Turkey and Djibouti in providing a haven for the business operations of militant groups.