Economists are warning that a global shipping emissions levy could have a negative impact on international trade.

It will also have a much more costly impact on shipping than the alternatives being considered, they believe.

This week, legislators at the International Maritime Organization are seeking a compromise or agreement on an economic measure to apply to shipping emissions.

The argument is that this is the only way to get shipping to decarbonise by 2050.

There are two main proposals on the table as member states gather for the Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting in London.

One is a levy, or feebate proposal, in which a price is set on a tonne of CO2.

The other is called a flexibility mechanism, whereby vessels need to meet a clean energy benchmark and are issued with remedial or compliance units.

Some researchers have likened it to the FuelEU Maritime rules.

Professor Paula Pereda and a team of economic researchers at Brazil’s University of Sao Paulo and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro have forecast the impact of both proposals.

The work is similar to that done by DNV and UNCTAD when they were asked by the IMO to assess the impact of the proposals earlier this year, but in much more detail, according to Pereda.

She told TradeWinds: “We did the same thing, calculated costs of implementing the measures.

“My team of economic researchers calculated [the impact] on ships but also the maritime trade flows to and from more than 100 countries.”

The high level or headline outcomes of the modelling for the fleet was largely similar to those from DNV, with slight differences, but the increased detail on the impact on trade flows was notably different.

The database they used comes from the Global Trade Analysis Project, which is updated regularly by institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission.

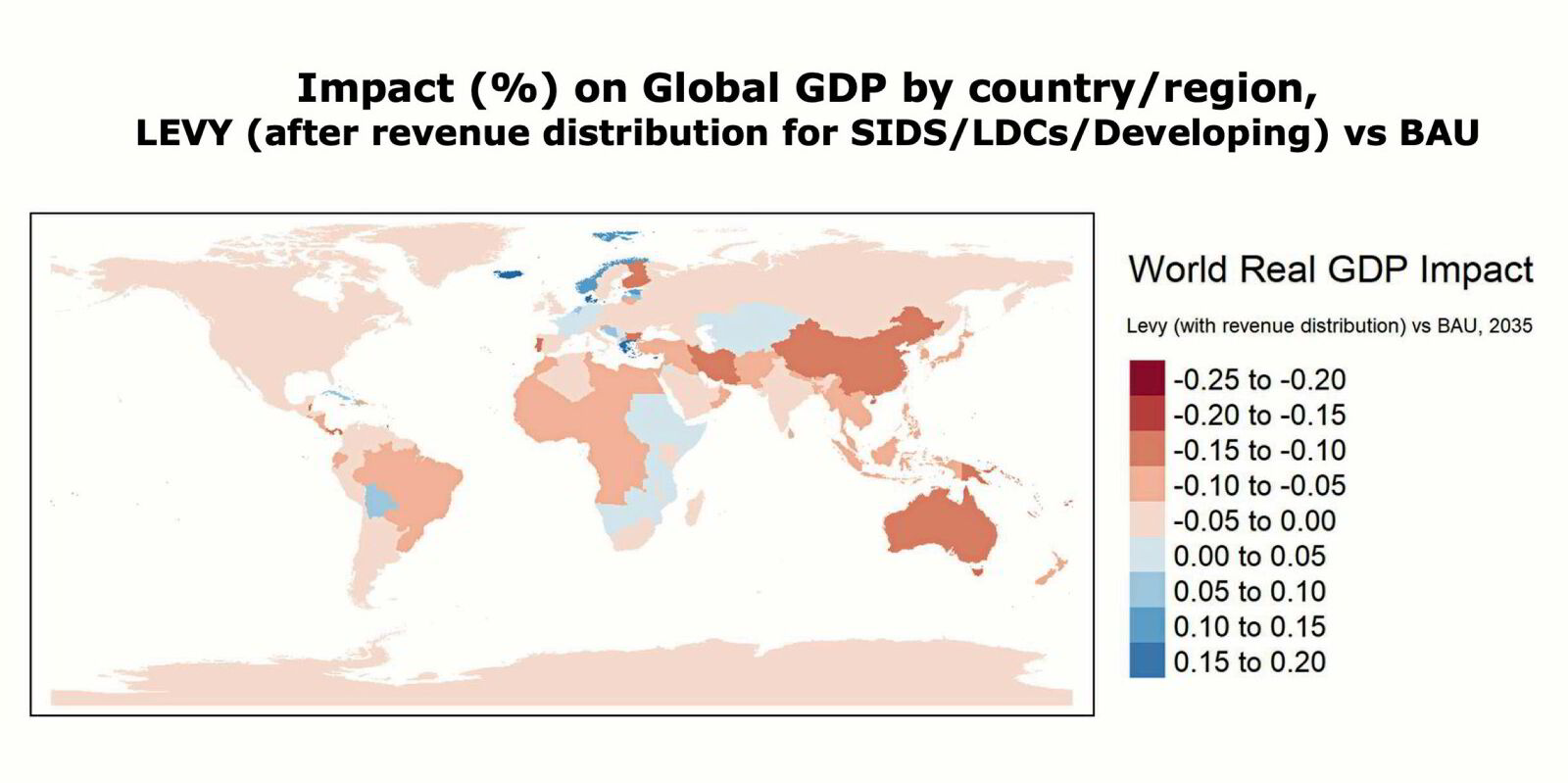

Pereda’s results paint a much more worrying impact on the GDP of a number of countries, notably developing countries (see map), including the effect on food security.

They were highlighted as possible obstacles that need to be resolved for the IMO to find consensus this week.

Brazil, Russia, India, China and even Norway are against the idea of a levy on shipping, even though support for such measures seems to be growing.

As the next round to talks begin, Caribbean countries have also come out in favour of the levy.

A flexibility mechanism would raise much less revenue from shipping, notably in the early years of the transition, according to Pereda, but still achieve the same goals.

She warned that it is hard to look at the impact of the fleet in 2050 due to errors in the economic models being exaggerated over time, but also said it would be myopic to look only at 2050 and not the early impacts in 2030.

Greenhouse Gas Fuel Intensity (GFI) is a mechanism using annual well-to-wake greenhouse gas emissions or tank-to-wake greenhouse gas emissions, with sustainability criteria, per energy unit used. The GFI is determined by the IMO’s methodology. There are multiple variants of this idea, with route-based differentiation and correction factors for eligible ports. There is also a range of approaches to managing the well-to-wake emissions associated with a GFI based on tank-to-wake emissions associated directly with the vessel, including correction factors and timelines for the phase-out of certain fuels.

GFI Flexibility — also known as compliance pooling and trading — provides participants with an alternative means of complying with the GFI requirement. It allows the trading of compliance units among participants who have a surplus or a deficit of compliance units as computed in comparison with the emissions that would have been generated by the ship had a GFI-compliant fuel been used. A compliance unit is a mass of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). There are two versions of this idea. In the first, the complying entity is the vessel; in the second, the complying entity is a pool of vessels. In this proposal, there is also a revenue body that buys surplus compliance units if their market price falls below a pre-determined amount. It can sell surplus compliance units if the market price goes above a pre-determined amount.

Levy/fee is a system in which a levy is charged on all emissions produced by a ship (US dollars per tonne of CO2e). This is collected by a revenue body. Amounts are then disbursed for multiple purposes, including a reward for vessels that use eligible fuels. The reward is a predetermined amount per unit of energy from eligible fuels used. By implication, with the levy and reward fixed, the funds available for other purposes must float as the balancing item in the budget.

Feebate is broadly similar to the levy system, with the exception that the levy rate is the floating item used to balance the budget.