The International Maritime Organization is close to redrawing its decarbonisation target but remains critically split over economic measures and compensation packages for developing countries.

Sources inside the IMO told TradeWinds that member states are now close to a consensus on raising decarbonisation targets as a result of behind-the-scenes negotiations this week.

Judging by the weight of statements made by member states at the environment meeting, it seems to be heading for net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 — the minimum required to keep shipping in line with the Paris Agreement on climate change.

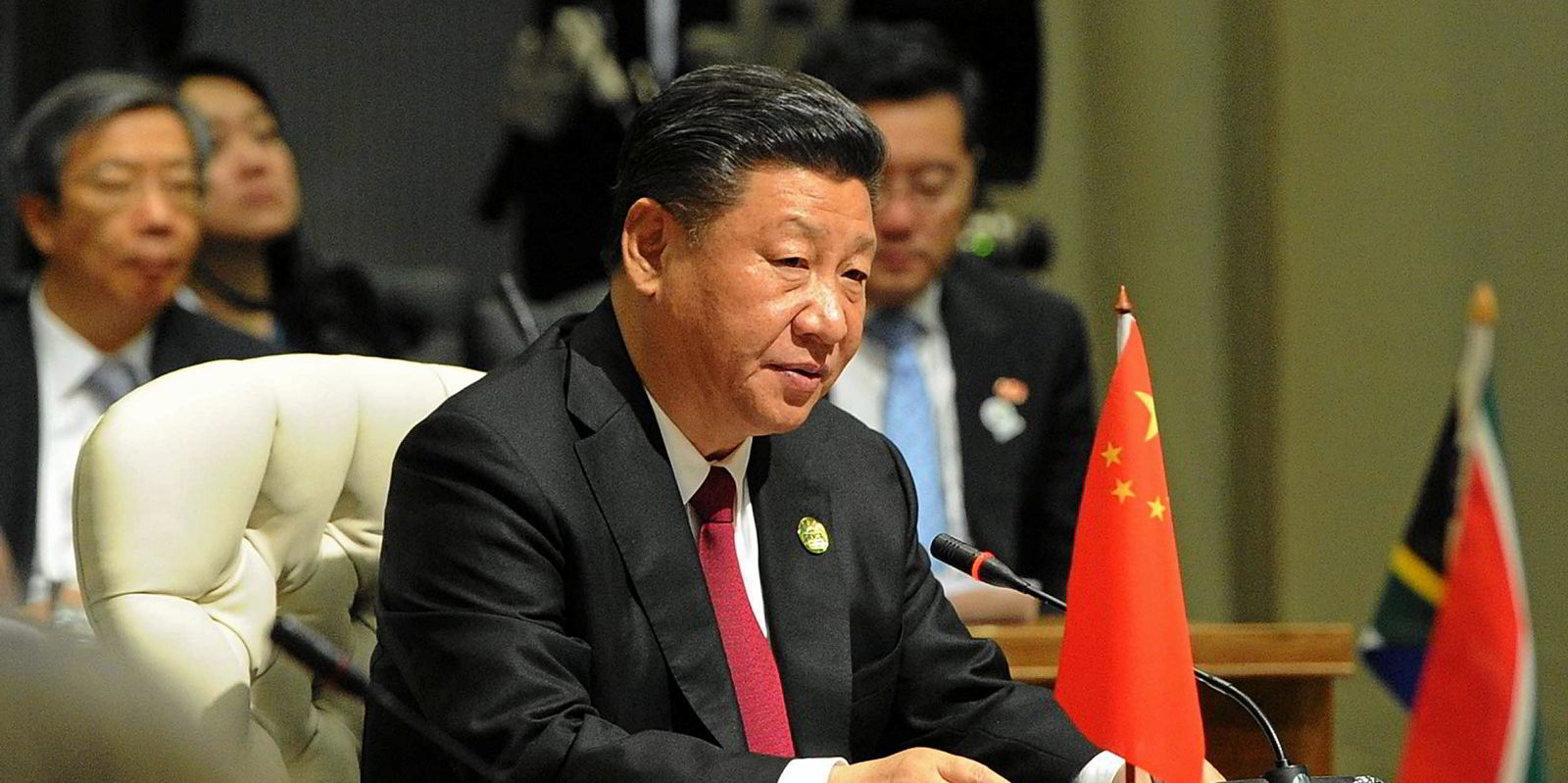

The vaguer term of net zero by “around mid-century” was backed by China and Saudi Arabia, which called for a “flexible approach” to future emissions targets.

But the UK insisted that the decarbonisation targets needed to be decided “in terms that cannot be misunderstood”.

The US, which is backing zero emissions by 2050, said the IMO should make a decision based on a “clear and credible pathway” that is also “ambitious and feasible”.

The IMO also appeared to be close to an agreement on developing a Global Fuel Standard (GFS) in which the carbon intensity of marine fuels would be reduced over time.

The main point of contention is whether the GFS can be tied to a carbon emission levy as called for by Greece and other European countries.

For many South American countries and China, that is a step too far because of the higher shipping costs they would have to endure.

They suggest a levy would disproportionally penalise countries that are reliant on shipping and are located far from their major markets.

China earlier encouraged developing countries not to accept a levy on greenhouse gas emissions as a market-based measure to incentivise decarbonisation.

‘Must be compensated’

Uruguay urged the IMO: “Don’t penalise countries on the basis of their distance from their main markets.”

The South American nation added that such a levy could also jeopardise global food security.

The Solomon Islands, which is backing a levy, pointed out that there is no way shipping can avoid higher costs.

“Transition without any cost effect is an illusion,” the Pacific island nation said.

The funds raised through a greenhouse gas levy would partly be used to compensate developing countries as well as funding research and development and subsidising the use of cleaner fuels.

The Cook Islands’ representative made it clear that Pacific island countries stood to lose a lot from the IMO’s decarbonisation efforts and “must be compensated”.

She said the Cook Islands is only responsible for 0.03% of greenhouse gas emissions, while G20 countries produce 80%.

The representative pointed out that the Cook Islands is a “climate-vulnerable country” and could be additionally economically disadvantaged by the measures under discussion.

She urged the IMO to develop rules that “do not place an additional burden on Pacific island countries”.

The most likely outcome will be the commissioning of a report by the IMO that will look at the economic impact of climate-change measures.

The question for the IMO member states is whether the regulator can afford to wait for the impact report before enacting the measures to help meet its raised decarbonisation targets.