A rallying call by International Maritime Organization secretary general Kitack Lim for governments to be “ambitious and bold” has primed the regulator to make a historic commitment to decarbonise shipping by 2050.

As TradeWinds went to press, a draft agreement was being put together by a working group requiring governments to achieve net zero or zero greenhouse gas emissions in the next 25 years.

The draft will be put forward for adoption at the upcoming Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) meeting between 3 and 10 July.

But, the working group was dramatically split over the economic measures that are viewed as critical to achieving full decarbonisation.

China, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil were particularly vocal over the negative economic impact of a carbon emission levy-based system — which represents four out of six proposals — on countries that are located far from their markets.

China is instead proposing an International Maritime Sustainable Fuels Fund.

Argentina pointed out that some carbon pricing measures would disadvantage countries in the southern hemisphere and benefit those in the north.

There has been strong support for a levy system among many IMO members states because it is viewed as the least complicated to introduce and could provide an immediate incentive for shipowners to use zero-emission fuels.

It now seems likely that an impact study on the various economic measures will be ordered by the IMO, which could further delay a decision.

The UK, US and European Union want medium-term measures — including both carbon pricing and technical measures such as a global carbon intensity fuel standard — to be adopted as early as 2025 to enter into force by 2027.

Early adoption of such measures is again viewed as critical to the decarbonisation time schedule to 2050.

But questions were raised about whether that timeline is feasible, given the time it would take to produce an impact report into market-based measures.

The working group was able to agree on some points. There was a broad consensus that the IMO strategy should include “just transition that leaves no one behind”, referring to developing countries.

It will also prioritise safety and the well-being of seafarers.

There is also a series of annual assessments of emissions and the carbon intensity of the global fleet lined up to monitor progress toward the level of ambition.

A review of the IMO’s decarbonisation strategy, including the level of ambition, will be scheduled in 2030.

But, the review will only allow the IMO to raise its decarbonisation ambitions, there will be no what the US described as “backsliding,” on decarbonisation targets.

The general view is the IMO will reach a consensus on a target to decarbonise by 2050.

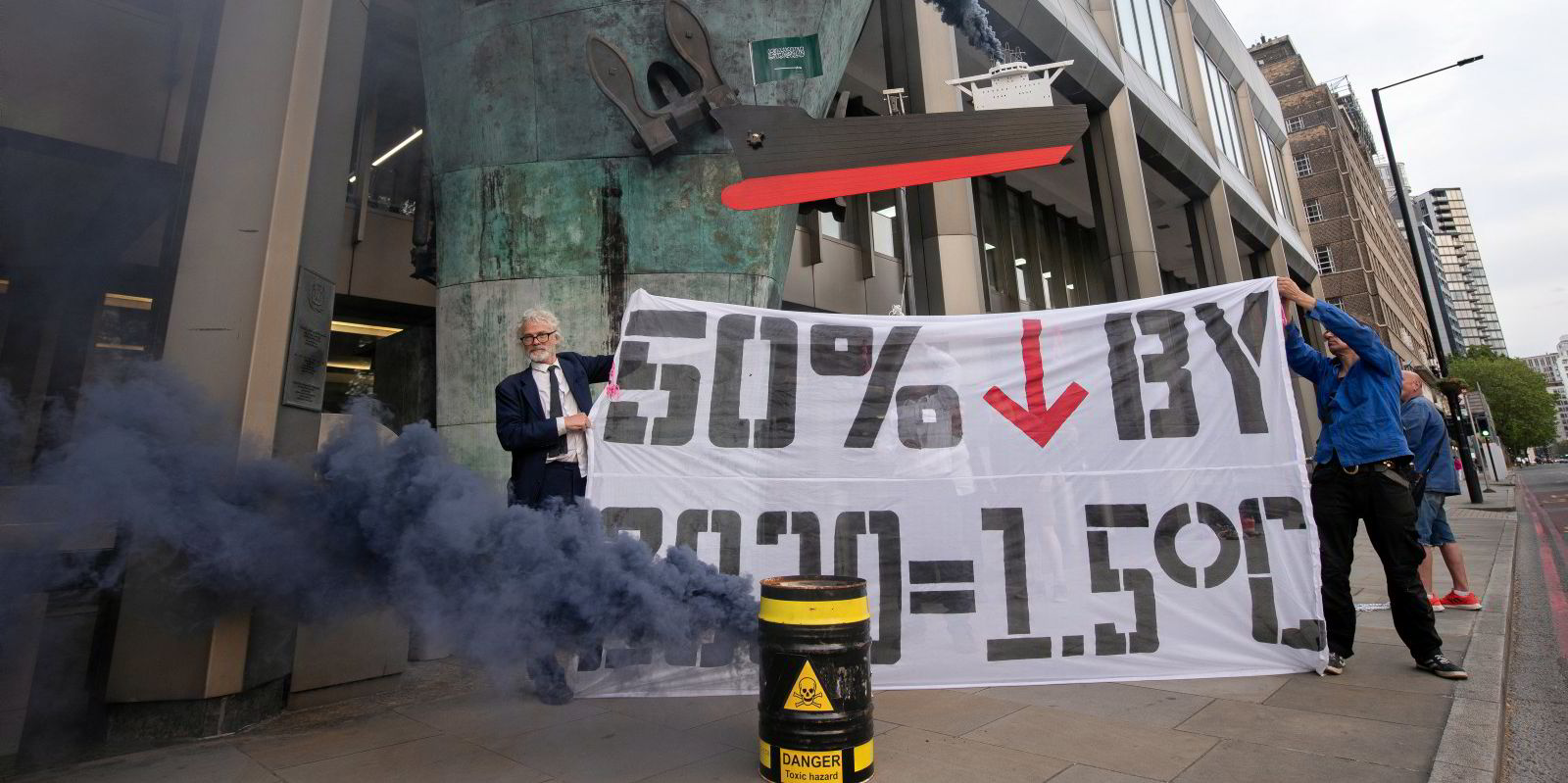

The 2050 date was not even mentioned in a protest outside the IMO by Ocean Rebellion. The environmental lobby group instead focused on its call to halve emissions by 2030.

But it is unclear whether the IMO is ready to commit to absolute zero emissions or net zero, which will allow for offsetting.

It is still up for debate whether the target will be a well-to-wake or life-cycle emissions that incorporate emissions generated in the fuel production process.

Some argue the IMO remit is limited to regulating tank-to-wake emissions.

The intermediary targets in 2030 and 2040 are increasingly becoming the focus of attention.

Among the more ambitious proposals, the UK, Canada, US and others are calling for the IMO to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on a life-cycle basis by 37% by 2030 and 96% by 2040, compared with 2008.

A report by CE Delft submitted to the IMO concluded that ships could achieve 28% to 47% emissions reduction by 2030, compared to 2008 levels, by deploying 5% to 10% zero or near-zero emission fuels.

A study commissioned by the IMO and undertaken by DNV and Ricardo suggested that a 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 could be “challenging” without a commitment from the IMO to decarbonise.

“More ambitious policies are needed very soon to come into effect by 2025 in order to meet the 2030 target of this scenario,” the report said.