When Rolls-Royce demonstrated in Copenhagen harbour how a tug could be operated remotely, it no doubt generated mixed feelings among member states of the IMO.

On one side of the table are countries such as Norway, Japan, China and South Korea, which see huge benefits from using this emerging technology and are developing what are termed Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS).

In contrast, others such as the Philippines and India are likely to harbour serious concerns that it could stifle their supply of seafarers to the world's fleet.

The reality and implications of automation and autonomous ships probably lies somewhere in between. Some industry participants argue it is a redefining of roles, rather than a means of cutting jobs.

Among them, and someone at the sharp end of what could become a heated tug-of-war, is Kevin Daffey, Rolls-Royce's marine director of engineering and technology.

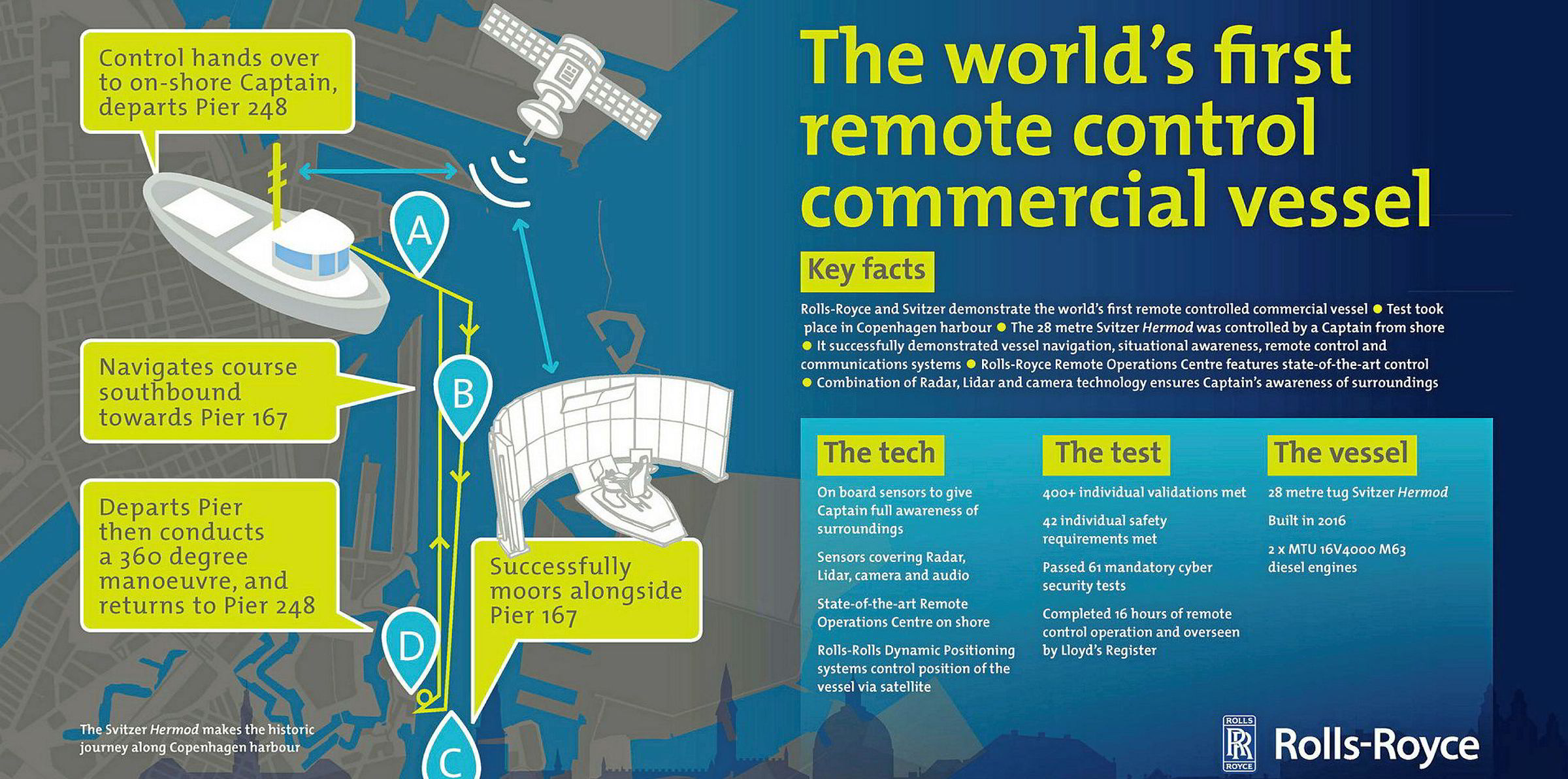

The demonstration of the 28-metre tug Svitzer Hermod (built 2016), in cooperation with Svitzer, was not the start but the latest stage in Rolls-Royce’s autonomous ship developments. Daffey says this process can be traced back to the mid-2000s when the company introduced its first dynamic positioning system, later its ACO automation system, and in 2014 with the announcement of its futuristic operation experience (oX) bridge concept.

But unmanned ships are not going to happen overnight.

“You can see a transition where you start with a manned vessel and you begin to take some of the crew off and replace some functions they do on the vessel, moving these functions to shore,” Daffey tells TradeWinds.

What the Copenhagen harbour demonstration showed was how experienced chief engineers, for example, could be brought onshore and their expertise used to guide those onboard with handling equipment, carrying out maintenance and to intervene remotely when required.

“So, if you took a chief engineer off every tug [in a fleet], you could have one single chief engineer ashore monitoring all the systems of all the tugs in operation and he could communicate back to an able hand doing, for example, the rope handling,” Daffey says.

The onboard seafarer could just as easily “get his toolkit out and make adjustments or do some basic maintenance based upon what the chief engineer’s instructions are”.

It reduces the amount of crewing onboard and, from the remote operating centre, uses chief engineers across several ships rather than one.

Those onshore chief engineers could operate in shifts, make better use of their time and get rested every night at home.

That in itself presents a business case, but Daffey says “the ultimate substantiation is a completely autonomous tug where we have already come up with some concept designs”.

Daffey adds that all the same "senses", as well as knowledge and experience, would be needed, something Rolls-Royce became aware of during that testing of the world’s first remote-controlled tug in the Danish capital.

The remotely located master had to wait for the tug’s motion to be seen on the video wall to confirm the thruster was manoeuvring a second tug during the demonstration. Onboard, the master would have heard the thrusters and felt the vibrations. Consequently, a speaker was introduced in the remote control centre and a deck created that vibrates when certain actions are successfully implemented.

That Svitzer Hermod project, dubbed Sisu, started in 2016, also working with Lloyd’s Register and the Danish Maritime Authority (DMA). The remote control centre was built on the quayside next to Svitzer’s office and included standard bridge equipment, such as radar, an electronic chart display information system and replicating onboard systems with normal azimuth control.

The project has since moved onto the next stage, the fitting of rope-catching equipment to the tug, while upgrading the software and some of the spatial awareness equipment. By the beginning of next year, much of the vessel’s operations will have been demonstrated remotely.

It will be able to hold a position, manoeuvre, automatically catch a rope thrown from another vessel and handle waypoint tracking.

“That means by 2020, we could potentially create a remote and autonomous tug that could replace existing tugs,” Daffey says.

He adds that there has been quite a lot of interest from other tug operators and shipyards to progress the technology.

Tugs have been a good launch pad as, in and around ports, it is easy to set up a wireless or 4G connection, enabling vast amounts of voyage data traffic to be captured.

Also, demonstrations such as the Svitzer Hermod can be regulated by the port authority. IMO rules are not applicable as the vessel is not operating on the open seas.

Daffey says the DMA was keen to assist but, because it was the first time this technology had been shown and was not production-ready, it required crew to stay onboard the Svitzer Hermod.

But he says if a solid safety case can be presented to the DMA, it may not be long before the tug can be demonstrated unmanned.

Rolls-Royce is developing the system but also uses suppliers, including for sensors. Google has been assisting with its machine-learning algorithms to help in identifying vessels. A web scrape of many millions of images has been used for training an artificial-intelligence algorithm.

Control of the vessel is based on a modified version of Rolls-Royce’s dynamic positioning system. Layered on top of that is the company’s automatic navigation system, its intelligent awareness system, and the communication and connectivity system.

Daffey sees harbour-operated vessels as the first beneficiaries of autonomous shipping, including remote pilotage units and partially autonomous ferries, possibly even remotely controlled or with at least a smaller crew (especially ferries operating during unsociable hours). Rolls-Royce has been working with Finferries for the past two years.

Norway’s Kongsberg, which is in the process of acquiring Rolls-Royce Commercial Marine, also has a programme with Yara for the movement of fertiliser along the Norwegian coast using the world’s first fully electric and autonomous container vessel — the Yara Birkeland — upon its completion.

Earlier this month, it was announced that Yara had signed a contract — worth around NOK 250m ($29.7m) — with Vard to build the vessel, which is set for delivery in the first quarter of 2020 from the shipbuilder’s yard in Brevik. Vard Braila in Romania is responsible for constructing the hull.

Svein Tore Holsether, president and chief executive of Yara, says a vessel “like Yara Birkeland has never been built”.

But for autonomous ships operating in international waters, changes to IMO regulations will be needed, something that could take years to put in place.

Daffey says securing agreement among 150 countries is not easy. Some nations are very supportive of the technology, others are quite sanguine and a third group are strongly opposed.

“There are constituencies of people who feel threatened by this type of technology,” he says. “From our perspective, we see this as a change, but it is moving people from ship to shore. It is a transfer of jobs rather than a pure replacement."

To read the full Ship Design & Innovation report be sure to pick up this week's print edition of TradeWinds.