With one or two exceptions, the majority of shipowners were sceptical about autonomous vessels three years ago, says Rolls-Royce marine director of engineering and technology Kevin Daffey.

But he says opinion has been shifting, with “most companies with a forward-looking view” now curious about their benefits.

And, he adds, while investment remains a hurdle for the nascent sector, some companies are willing to explore the designs and demonstrate whether the technology works in practice, among them Svitzer of Denmark.

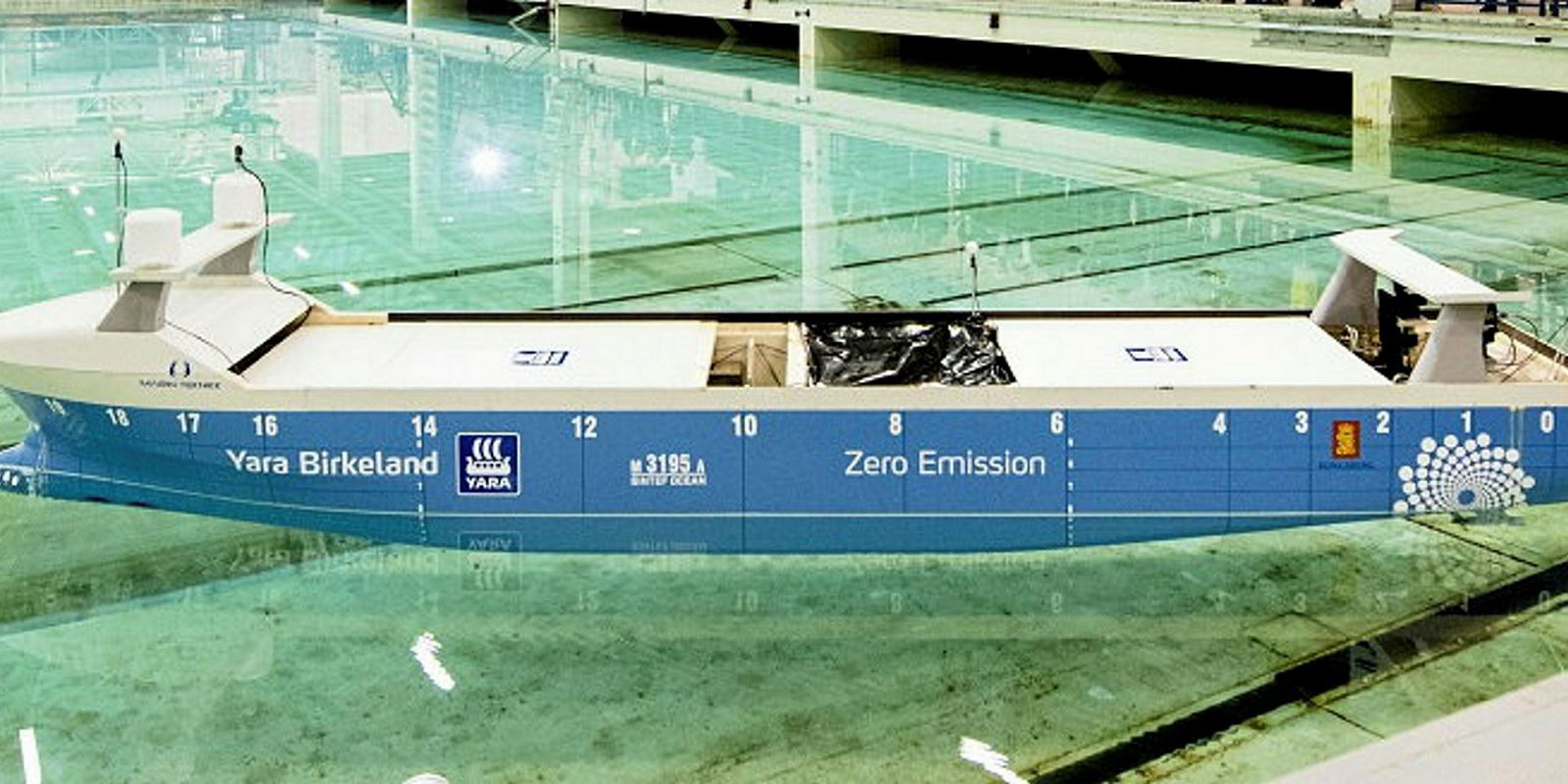

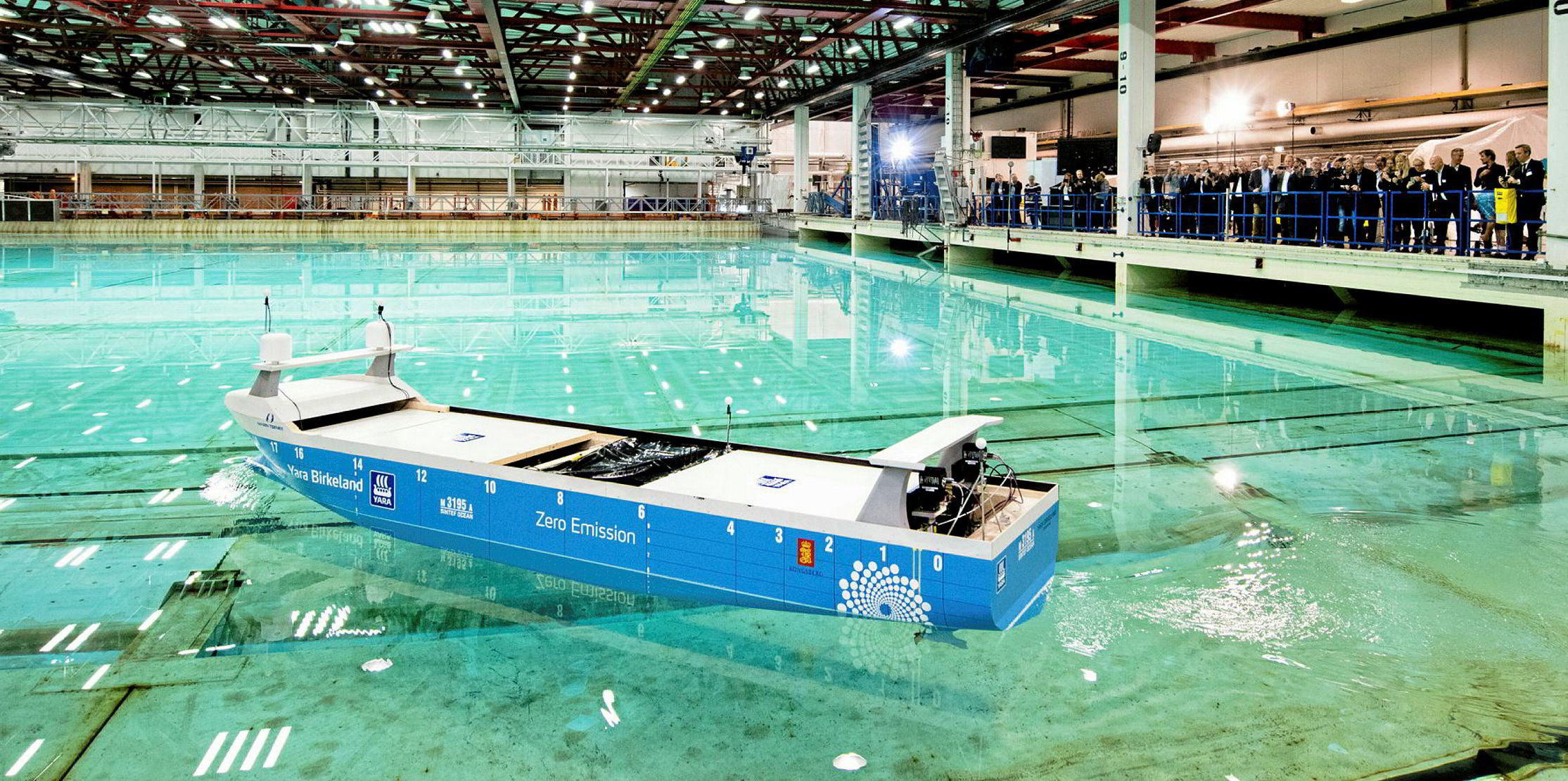

Daffey says the fact Yara is prepared to develop the fully autonomous Yara Birkeland will help.

But, equally, new guidelines from regulators could be a game changer. “Once the regulations are sorted out, I think we will see more of a rapid take-up of the technology,” Daffey says.

Crucial will be the first flag state to approve the technology. If Norway gives the go-ahead to the Yara Birkeland, Daffey says: “I can see other flag states saying, ‘Come and talk to us’.”

The IMO legal committee is undertaking a regulatory scoping exercise that is due to be completed in 2020.

Nick Shaw, global head of shipping at law firm Reed Smith, said in a TradeWinds article in July that the IMO believes the introduction of autonomous ships will make the industry safer, more efficient and environmentally friendly.

But it also recognises that the vessels will create issues for maritime conventions that were not drafted with unmanned vessels in mind.

These include the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, and the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers.

Nick Brown, Lloyd’s Register's marine and offshore director, says the class society has ensured in its certification framework that automation is not compromised.

He points to the benefits of automation, such as reducing the need for maintenance crew, and the potential for remote diagnostics in monitoring main engines and generators, and maintenance, such as opening up a bearing for survey, to be carried out according to data and not intervals.

Brown says shipping needs to overcome its nervousness about data and share it for the benefit of all, not least to improve reliability of maintenance regimes.

He insists the industry needs to reach a point where the seafarer is a purely operational role. He adds that the equipment onboard vessels is becoming increasingly complicated and, in many cases, the only way to trace a fault is by plugging in a laptop.

He adds that if maintenance moves towards an oil refinery-style of planned shutdowns, in a dry docking or by riding crew, it opens the doors to reducing the number of people on a bulker, for example, from 22 to 12 or 15.

“Unfortunately, trends today suggest there are still too many collisions and, therefore, I can’t see there being a widely accepted agreement that we don’t need people on bridges as watchkeepers any time soon,” Brown says.

“A well-known statistic is that 90% of accidents have some form of human element as part of the root cause, and we have to recognise that the workload of people onboard is not reducing at the moment.”

The highest level of autonomy Lloyd’s Register has certified is AL4 for the 28-metre tug Svitzer Hermod (built 2016). The next step — AL5 — involves no one being onboard.

Daffey says it is too early to say what effect Rolls-Royce Commercial Marine’s pending sale to Norway’s Kongsberg will have. Until the takeover has been flagged through by the antitrust authorities, they will continue to operate as separate companies.

A lot of the technologies are complementary and Daffey sees opportunities to build on those synergies.