Many seafarers’ centres used to have bars and overnight facilities but shorter time in port and tighter alcohol rules mean beverages are sold in much smaller quantities and only in appropriate locations, says Mission to Seafarers' secretary general Reverend Canon Andrew Wright.

“In many places, we don’t offer beer at all now,” he says.

The downside is that declining alcohol and food sales have erodedsteady income streams that help centres sustain themselves, although this has been partly offset by sales of first phone cards and now SIM cards.

The centre in Southampton is among those that have fallen victim. After 130 years of service, the last fully manned seafarers facility in the area closed in 2016.

Too few visitors

Only one in 50 visiting seafarers used the centre — an ecumenical project involving four societies including the Mission to Seafarers — meaning it was no longer viable.

The UK Chamber of Shipping, in an article focusing on the closure, and others Milford Haven and Cardiff, quoted John Green of the Apostleship of the Sea (AoS) charity that most seafarers simply no longer had time to visit centres during their “brief stay in port”.

He continued: “It is really the large seafarers' centres that have closed, beginning 20 to 25 years ago. Those with accommodation, chapels, dance halls and canteens weren’t able to generate enough revenue to be sustainable but, more importantly, they weren’t meeting the needs of most of the seafarers visiting UK ports.”

He added that the focus had switched to visiting seafarers on their ships, including chaplains being equipped with mobile wifi hotspots so crew can connect with those at home without having to go ashore.

Ship visits

This may help explain the 8% increase in ship visits last year by the Mission and why it and other charities such as the AoS and the Sailors’ Society collaborate increasingly in operating centres.

Even where the ships and companies are good — we have seen a lot of improvement in seafarers’ welfare — these guys are still away from home for very long periods, work under significant pressure and land often in remote and difficult ports

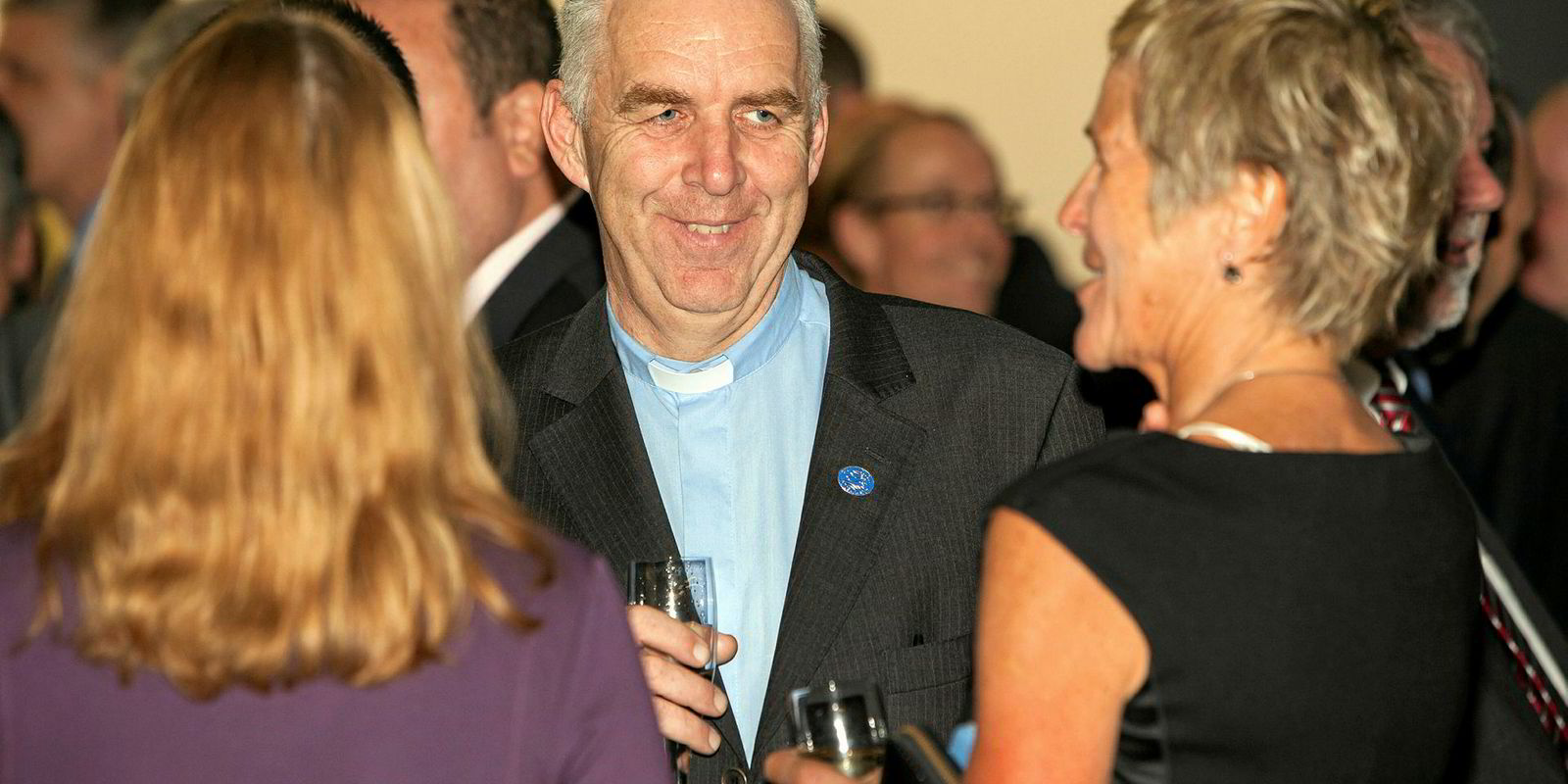

Reverend Canon Andrew Wright

At one time, some ports, including Southampton, would have had up to three individual centres vying for business.

Wright says many ships now also provide far better accommodation — but the downside of single cabins is it discourages crews from mixing and can increase isolation.

“Even where the ships and companies are good — we have seen a lot of improvement in seafarers’ welfare — these guys are still away from home for very long periods, work under significant pressure and land often in remote and difficult ports,” Wright says.

Mental health problems among seafarers remain prevalent and that is why organisations such as the Mission are keener than ever to get onboard ships, to listen to seafarers and direct them to further help.

The Mission’s London headquarters spends about £5.5m ($6.9m) per year, which does not cover all the centres around the world and many operations that depend on local funding.