Ocean voyages could double the fuel savings for ships using wind-assisted propulsion compared with test results from shortsea routes, according to research into voyage optimisation with Flettner rotors.

Rotor Sails could deliver fuel savings of up to 20% on deepsea routes, compared with about 10% recorded so far in the North and Baltic seas, according to studies by Dutch company C-Job Naval Architects using voyage optimisation and weather routing software developed by Finland’s NAPA.

“In the northern Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the benefit from wind can push Flettner rotor savings to 20%,” says Robin Berendschot, a Delft University of Technology graduate in marine technology working on a research programme to optimise ship designs for the rotor sails at C-Job.

Norsepower’s Flettner rotors have demonstrated fuel savings of up to about 10% when fitted to Bore's 9,700-dwt ro-ro the Estraden (built 1999) and Viking Line's dual-fuel, 57,565-gt cruise ferry Viking Grace (built 2013), both of which operate around Europe. Results are not yet known for the 109,647-dwt LR2 product tanker Maersk Pelican (built 2008), which was fitted with rotors last year and sails worldwide.

Design certificate

Last week, Norsepower was awarded the first-ever type-approval design certificate for a commercial ship’s auxiliary wind-propulsion system from classification society DNV GL.

Berendschot says voyage optimisation can really exploit the benefit from Flettner rotors by forecasting when it is worth deviating from straight-line sailing into areas with strong winds. This is especially true on the open ocean.

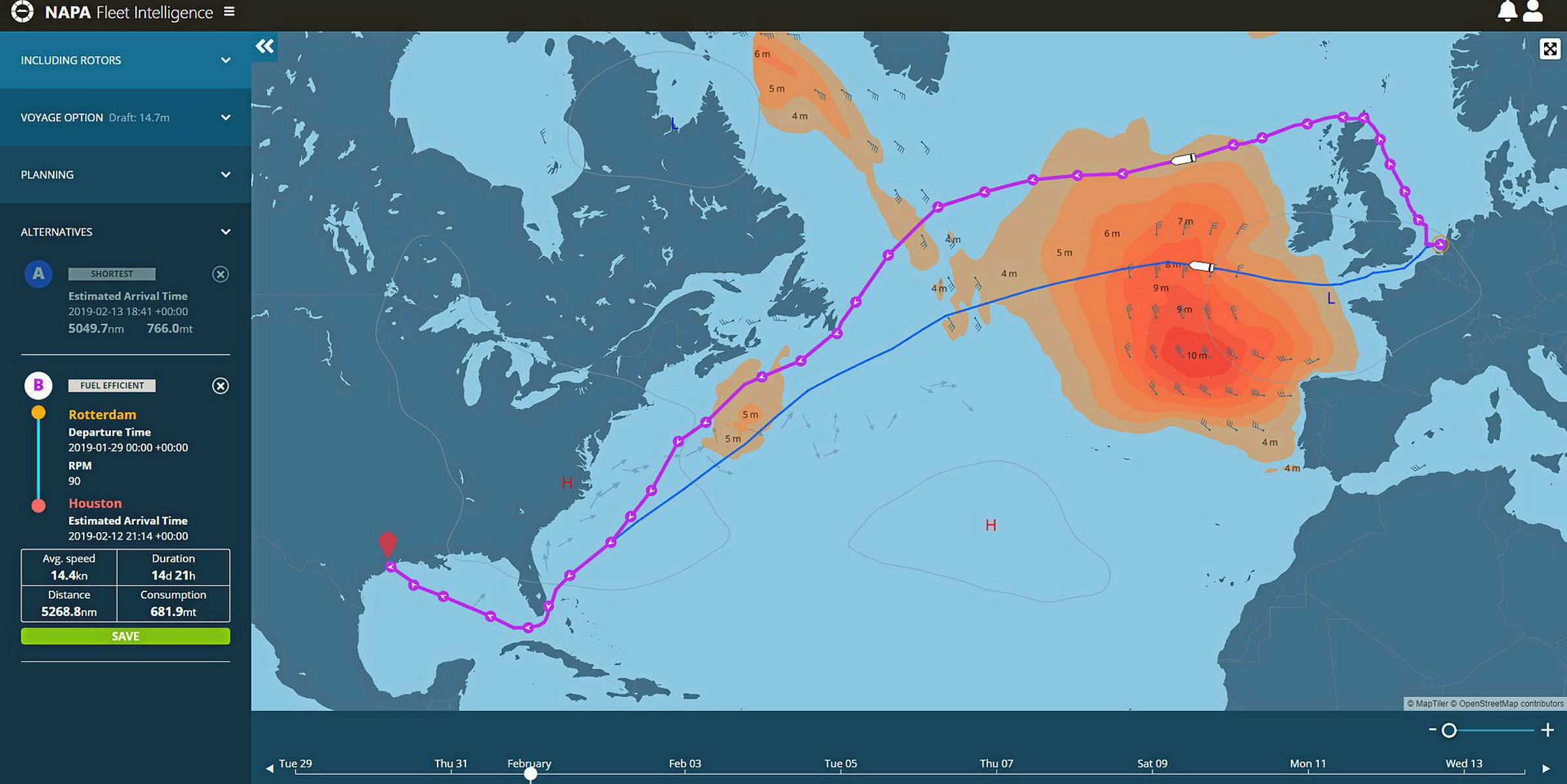

Claus Stigler, a senior software developer for NAPA, adds that voyage simulation alongside weather forecasts, information about currents and tides plus historic statistical climate data can all add up to predict which routes are best to take when using rotor sails.

“If you want to go from London across the Atlantic, [you can decide] at the mouth of the Thames, do you turn south to the English Channel or go north round Scotland?” Stigler says.

“And, if you take the southern route, do you then choose to go the great circle route across the Atlantic [the shortest course between two points on the surface of the globe] or go much further south to the Azores and pick up the winds there.”

He adds that changing the routing from the beginning of a voyage “has quite an effect on the overall fuel consumption that will be realised”.

Simulated savings

Simulation images attached to this story show how on a voyage by a midsize tanker from Rotterdam to Houston, equipped with two 30-metre-high rotors, it is possible to save 84.1 tonnes of fuel (11%) on a longer route north of Scotland than directly south via the English Channel.

Berendschot cites how yachts in the Volvo Ocean Race sail close to Brazil first to pick up the strongest winds when on the leg from Europe to South Africa. It suggests iron ore carriers sailing from Brazil to Asia could benefit strongly from the same conditions.

Research into finding geographic sweet spots for rotor sails still needs to be done. But he adds: “Depending on your business case, shipping companies regularly travelling on 19th century sailing routes could get potentially much more benefit from Flettner rotors.”

However, the main aim of Berendschot’s research is to optimise ship designs for Flettner rotors, particularly newbuildings, to maximise the savings. Reducing main engine size is a primary candidate for that, and could easily pay much of the cost of fitting rotors, he says.

“We currently apply a sea-margin for engine capacity, so we over design the engine to be able to sail in adverse weather conditions," he says. "But where you have a lot of wind, you have many benefits from the rotors [and] you may be able to reduce your installed engine capacity.”

Rotors also generate side forces, so hull design needs to be considered. Adding them can increase stability issues that necessitate widening a vessel’s beam, which would normally increase resistance. However, it can also create greater deck space for more rotors, creating a potentially virtuous circle.

“With full optimisation of vessels, a 20% saving on fuel costs is really accomplishable,” Berendschot says.