Shipyards are being urged to improve their ability to build low-emission vessels at competitive prices to help themselves survive the industry downturn.

Data from Clarksons Research showed the global orderbook stood at 157m dwt in August, which was a 17-year low.

With financing constraints, regulatory uncertainty and economic problems caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, only 5.7m cgt of newbuilding orders were placed between January and June — the lowest in 25 years for a six-month period.

Weak demand

With the International Maritime Organization’s decarbonisation rules scheduled to come into force by 2023, Maritime Strategies International managing director Adam Kent expects newbuilding demand to remain weak for another two years.

“We don't expect to see that trough will end until around 2022,” Kent said.

Still, Clarksons Research non-executive president Martin Stopford suggested that the investors who want to be the first movers in low-carbon technologies could orders ships if they have access to financing.

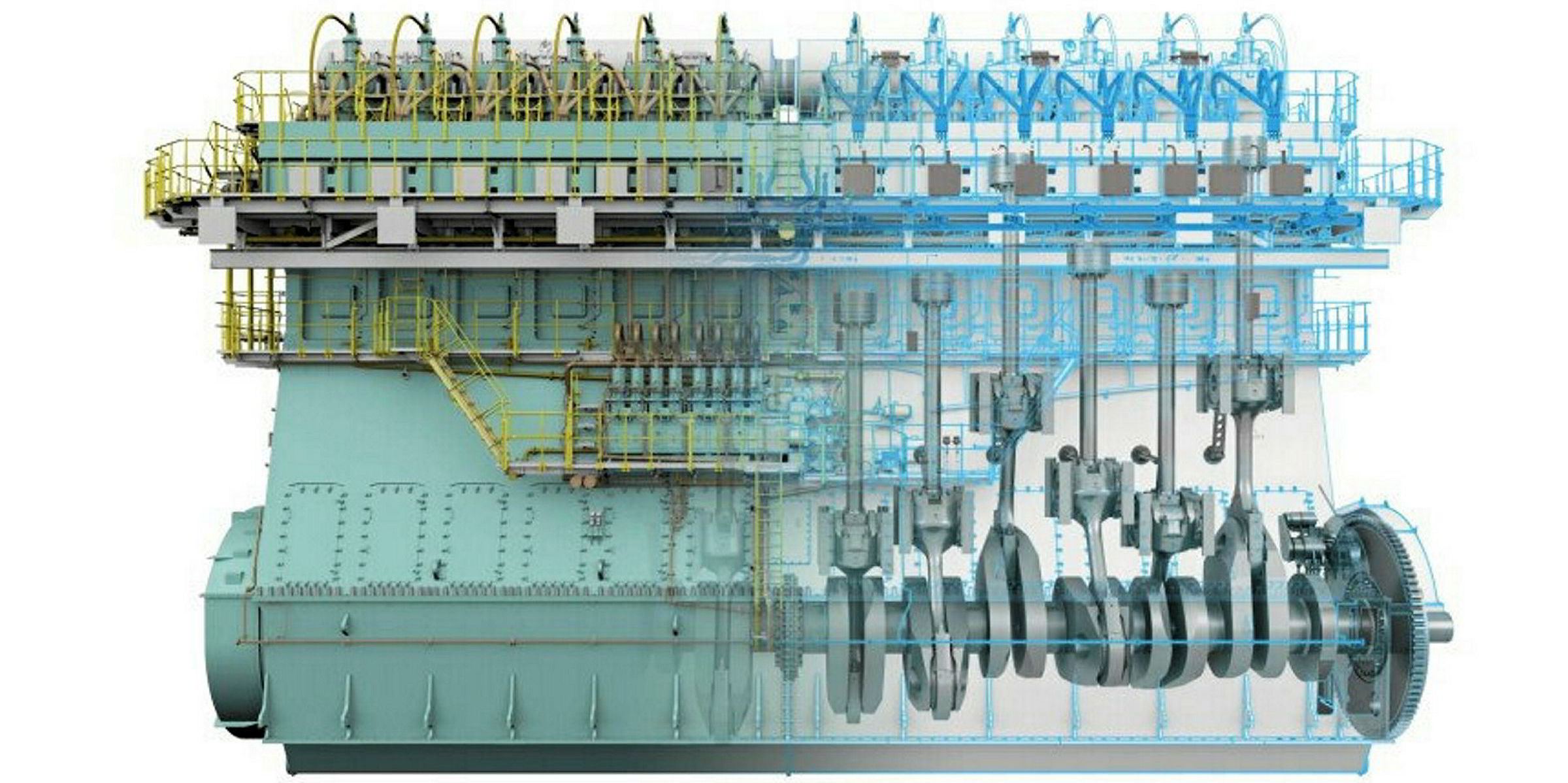

These technologies include propulsion systems that can run on gas and alternative fuels, automated kites and air lubrication systems for hulls.

Kent said shipyards may eventually need to absorb some costs of the new technologies to secure orders.

“Yards will have to think a little bit further outside the box and potentially bring forward some of the plans or designs,” he said.

Mergers ahead

Given most shipbuilders cannot afford thinner margins after years of limited income, Kent said more collaboration and consolidation may be necessary.

In China, the government has engineered the merger between China State Shipbuilding Corp and China Shipbuilding Industry Corp to create a giant yard group.

Hyundai Heavy Industries and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering — two of South Korea’s three major shipbuilders — have been in discussions over a merger, but the progress has been slow partly due to the time-consuming review by European competition authorities.

Japan has also seen continued consolidation efforts from shipyards such as Japan Marine United, while the government is pushing ClassNK and research institutes to jointly develop low-emission vessels with shipbuilders.

Kent agrees that yards can become more competitive by sharing costs in research and development activity, saying “cross collaboration” could be the key for survival.

With vessels built during the order booms earlier this century needing to be phased out, Kent said those who can commercialise ships with reduced emissions will eventually benefit from recovering newbuilding demand in the future.

“You will have seen huge swathes of replacement [orders] towards the second half of this decade,” he said.