Significant challenges are being presented to ship recyclers who have invested heavily to upgrade their yards in preparation for the Hong Kong International Convention on Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships set to take effect next June.

Indian yards are, for all practical purposes, fully compliant with the Hong Kong Convention, according to Haresh Parmar, honorary secretary of the Ship Recycling Industries Association of India.

It is a remarkable achievement given that only a few yards in Bangladesh are certified, and none in Pakistan have reached this standard.

But market players tell TradeWinds they fear this progress could now be lost due to an unprecedented market downturn driven by Russia’s war in Ukraine and the Red Sea Houthi terror.

These conflicts have kept many ageing tankers and boxships in operation, either absorbed by the dark fleet hauling Russian oil cargoes or covering longer routes as container ships detour around conflict zones in the Middle East.

These challenges overshadow what should have been a milestone celebration next year: more than a decade of regulatory efforts and substantial investments by recyclers aimed at establishing a thriving green recycling sector under the Hong Kong Convention.

After years and millions spent on creating regulations and building modern facilities, could the shipping industry’s green recycling ambitions now be derailed by geopolitical volatility?

The trouble faced by Indian ship recyclers is that despite costly efforts to upgrade yards the lack of tonnage entering the demolition markets has left them with a hefty bill without a return on investment.

Despite all the noise about going green, only 15 to 20 shipowners have been consistently sending ships to Alang for green recycling, according to Parmar.

Recycling sector insiders fear that the current challenges may deter non-compliant Hong Kong Convention yards elsewhere on the Indian subcontinent from pursuing upgrades. Such a decision, they warn, could drive these yards out of business permanently, significantly reducing global ship recycling capacity.

Today, capacity on the Indian subcontinent is a fraction of what it was just a few years ago.

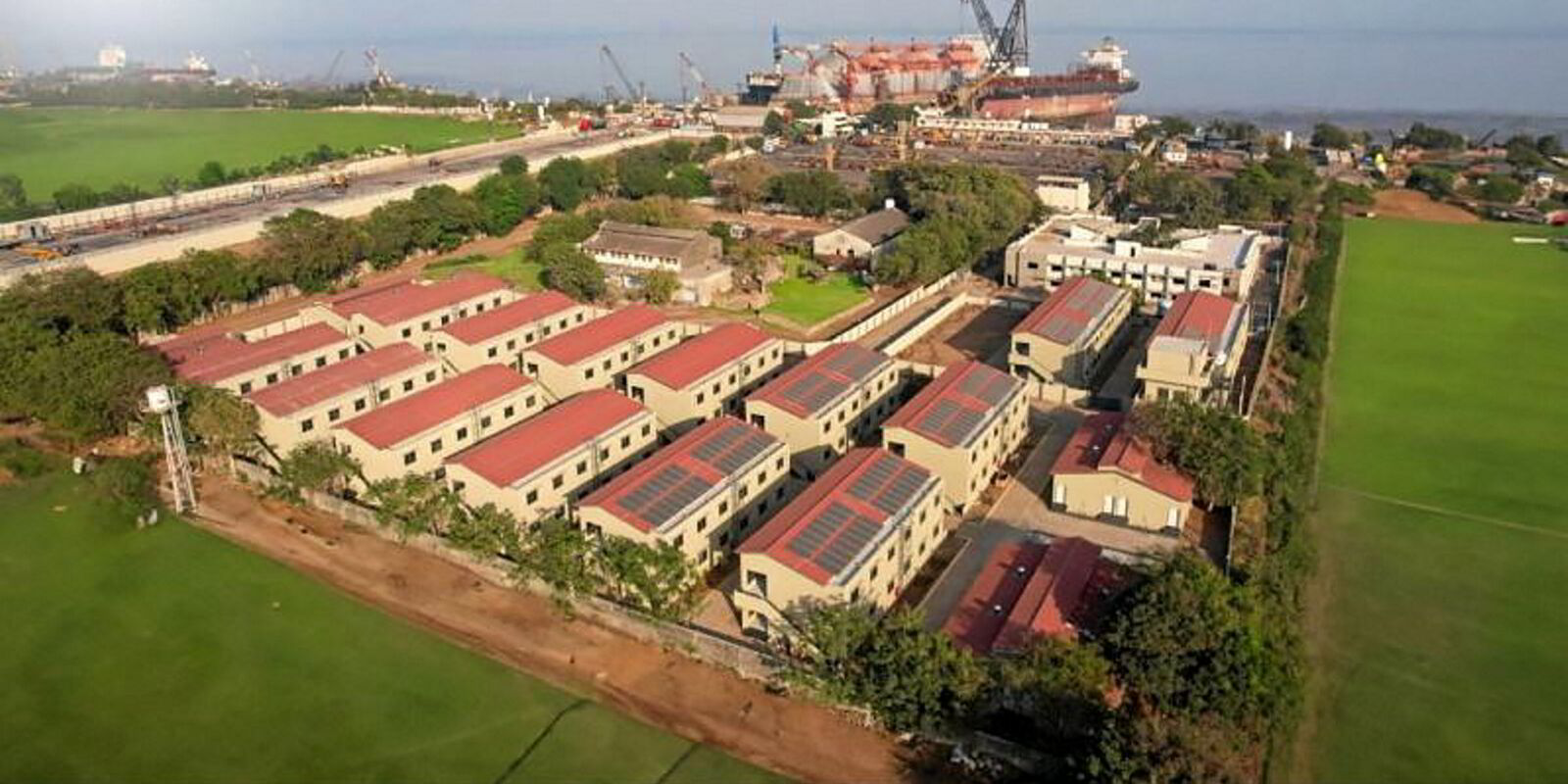

Only 20% of the 120 ship recycling yards in Alang are operational and usually work at less than 50% capacity.

Nayeem Noor, business development head at cash buyer GMS, set out the problems spawned by the slowdown: “This contraction has led to a significant decrease in the workforce and has strained the resources and infrastructure that have been built up over decades.”

Noor was one of three senior executives at Anil Sharma-led GMS to share their views with TradeWinds on the crisis faced by Indian ship recycling yards.

The industry in Alang has been a substantial employer in the Bhavnagar area, with about 13,500 workers at peak times.

Today, fewer than 2,400 workers remain employed, a staggering 82% to 85% reduction in direct employment.

Upskilling workers has been as important a part of the process as upgrading facilities to meet the Hong Kong Convention, and Noor and his colleagues described the loss of skilled labour as “particularly concerning”.

“As experienced workers leave the industry, the ship recycling sector faces the risk of losing the specialised skills that are critical to its operations.

“The reduction in workforce not only impacts the current operations but also poses long-term challenges to the industry’s ability to recover and compete globally,” Noor said.

He added that the downturn extends far beyond the workers directly employed in the yards.

The industry supports a vast ecosystem of related businesses and industries, all of which have been severely impacted.

“One of the most significant effects has been on the local steel industry, which relies heavily on recycled steel from ships,” Noor said.

“Historically, Alang’s ship recycling yards processed between 9,000 and 9,500 tonnes of steel daily, supplying raw materials to local re-rolling mills.

“However, with daily steel production now down to around 3,000 tonnes or lower, many re-rolling mills have shut down, leading to further job losses.”

Deteriorating facilities

Many yards in Alang invested heavily in upgrading their infrastructure — everything from new jetties, cranes and modern equipment to accommodation and medical facilities — in anticipation of a wave of ships coming in for green recycling.

Dr Anand Hiremath, GMS’ chief sustainability officer, expressed concerns that this infrastructure is now underutilised and deteriorating.

“The cost of maintaining idle yards is significant,” he said.

“The lack of revenue from ship recycling activities makes it difficult for yard owners to justify the expense of maintaining these facilities.

“This degradation is not only a financial issue but also a safety concern, as the risk of accidents increases if operations resume without proper repairs and maintenance,” Hiremath explained.

Hiremath added that the lack of activity had also disrupted the complex systems that govern operations at yards.

“These systems, which integrate production, health and safety, environmental management and human resources, are designed to ensure efficient and compliant operations.

“However, with fewer ships arriving for recycling, many of these systems have become obsolete or ineffective.

“The lack of activity has led to a decline in workplace morale, with employees facing uncertainty and job insecurity.

“This has resulted in a loss of interest in maintaining operational systems, further weakening the industry’s ability to function efficiently.

The International Maritime Organization’s Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships is aimed at ensuring that vessels being recycled do not pose any unnecessary risk to human health and safety or the environment.

The convention covers the design, construction, operation and preparation of vessels to facilitate safe and environmentally sound recycling, without compromising the safety and operational efficiency of ships.

Also covered under the rule is the operation of ship recycling facilities in a safe and environmentally sound manner, and the establishment of an appropriate enforcement mechanism for ship recycling, incorporating certification and reporting requirements.

On many occasions, it looked unlikely that the required threshold would ever be met.

Only in June 2023 was the Hong Kong Convention mandated after Bangladesh and Liberia handed over their ratification documents to then IMO secretary general Kitack Lim.

By signing up for the convention, Bangladesh and Liberia completed the two final missing pieces of the puzzle for the convention by bringing the number of ratifications required from both the recycling and flag-state sides to above the threshold required for entering the convention into force.

The Hong Kong Convention becomes law next June, but there are still issues that need to be resolved around the need for governments to align the convention with regulations such as the Basel Convention for the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Waste and the European Union’s Ship Recycling Regulation.

“As the industry contracts, there is also a risk that safety and environmental standards will be compromised, leading to potential accidents, environmental contamination and legal liabilities.”

Hiremath added that Alang had made significant progress in improving its health, safety and environmental (HSE) practices, driven by international pressure and the adoption of the Hong Kong Convention.

However, he cautioned that the decline in ship recycling activity had put these gains at risk.

“The erosion of HSE standards also threatens the industry’s reputation.

“Any lapses in safety or environmental compliance could undermine efforts to improve the industry’s image and make it more difficult to attract business in the future, particularly from shipowners committed to responsible recycling practices.”

Financial challenges

Yard owners in Alang are facing severe financial difficulties due to the downturn.

Maintaining idle yards, including costs for rent, loan interest, maintenance and certifications, is placing a heavy burden on owners, according to Rahul Singh, GMS sustainable ship recycling programme coordinator.

“Even those who manage to secure ships for recycling are struggling to turn a profit due to fluctuations in exchange rates, declining local markets and escalating operational costs,” he said.

Singh noted that the Gujarat Maritime Board, which plays a crucial role in overseeing the ship recycling industry in Alang, continues to apply its standard charges for yard owners, including plot rent, development fees, housing and utility charges.

“These fees are vital for maintaining the infrastructure and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the industry,” he said.

“However, for some yard owners, the cumulative costs can be challenging,” said Singh, who noted that in recognition of the current challenges, the government has introduced measures to provide relief, such as a 50% waiver on plot development charges and a 100% waiver on housing charges.

“While these initiatives offer some respite, the financial strain on yard owners remains a consideration,” he said.

“For yards that are not receiving any ships, the situation is even more dire. These yards incur significant costs without generating any revenue, making it difficult to resume operations.

“The financial strain is compounded by penalties imposed on yards that fail to recycle a prescribed minimum average light displacement tonnage of ships within a given five-year period. For yard owners already struggling financially, these fines could be the final blow.”

Critical Juncture

The ship recycling industry in Alang is at a critical juncture, according to the three GMS executives, who stressed that without immediate intervention and strategic planning, the industry risks long-term decline.

They argued that to revitalise the industry, all stakeholders, including the government, industry leaders and financial institutions, should collaborate on solutions to attract more ships for recycling, investment in retraining the workforce and financial support for yard owners.

One solution that often emerges in any troubled business environment is consolidation, as businesses buy weaker competitors to create larger, stronger companies.

Gaurav Mehta, director of Priya Blue Green Ship Recycling — one of the largest ship recyclers at Alang — and a speaker at the recent TradeWinds Ship Recycling Forum, said opportunities for consolidation at Alang are limited despite a large number of small, individually owned ship recycling plots.

Consolidation makes commercial sense, he said, but the Gujarat Maritime Board restricts any entity from owning more than four plots at any given time.

“Even if we want to grow further, we are not able to, which is tough for us,” he said.

Mehta said that there is a movement within the Gujarat board to allow entities to acquire more plots, thus allowing the creation of large facilities that he believes will be an economically viable solution.

Without such efforts, the GMS executives argued, the ship recycling industry in Alang may struggle to recover, with far-reaching consequences for the local economy and the global shipping industry.