Spanish oil giant Repsol has been facing billions of dollars in claims in a legal battle with Peru over an oil spill at one of its refineries two years ago that is expected to have long-term consequences for ecosystems in the South American country.

And now, it is looking to push some of the liability onto the Italian owner of a ship that was involved in the incident that touched off the spill.

Repsol subsidiary Refineria La Pampilla is pursuing a claim for nearly $198m plus interest against Fratelli d’Amico Armatori in a lawsuit in Peru, according to details disclosed in the Madrid oil company’s annual report.

Rome-based Fratelli d’Amico is the owner of the 158,000-dwt Mare Doricum (built 2009), a suezmax tanker that has been held up in Peruvian waters since crude spilled in January 2022.

The Italian company is preparing a $45m claim of its own against Repsol.

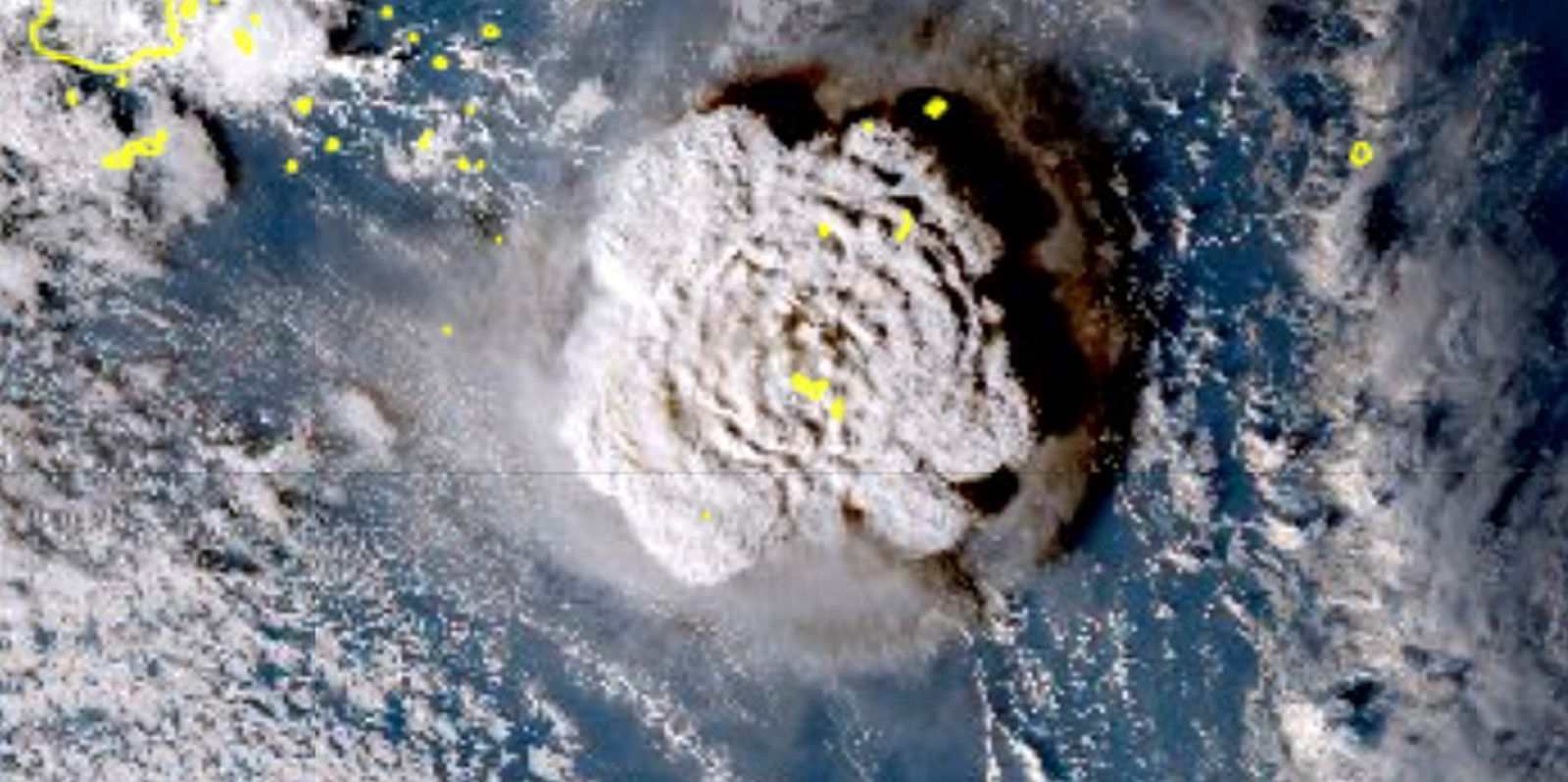

As TradeWinds has reported, the Mare Doricum was offloading crude at La Pampilla refinery near Lima in January 2022 when a wave from a massive volcanic eruption in Tonga struck.

An estimated 11,900 barrels of oil spilled into the water from an underwater pipeline at the refinery’s Terminal 2.

Repsol, which has faced the lion’s share of the ire from Peruvian officials over the ecological disaster, has accused the shipowner of “failing to fulfil its obligations” and said the Italian company also faces non-contractual liability.

“It has been proven in all expert evidence obtained that it was the uncontrolled and improper movement of the vessel and the fact that it shifted from the position envisaged to safely unload its cargo that caused the rupture of the underwater installation,” the oil company said in its annual report.

Repsol said that, under Peruvian and international law, the responsibility for the mooring process and its safety operation lies with the Mare Doricum’s captain and his employer.

Yet, the oil company said, Refineria La Pampilla has borne all the expenses alone, including costs to clean up the affected coastline and $300m in compensation to those impacted by it.

The Mare Doricum flies the Italian flag and is classed by Registro Italiano Navale.

At the time of the incident, it was insured by Standard Club before a merger made it part of NorthStandard.

TradeWinds has requested comment on Repsol’s latest legal action from a Fratelli d’Amico press representative.

After the spill, the Italian company said its crews followed all onboard protocols and procedures at the time of unloading and once oil was seen in the water, when operations were immediately halted.

As TradeWinds reported, the ship’s master, Captain Giacomo Pisani, wrote in documents on the day of the spill that the vessel experienced an “abnormal sea swell condition” that caused mooring lines to snap while the ship was discharging its cargo.

Fratelli d’Amico has requested out-of-court “conciliation” on its counterclaims against Repsol, an effort at settlement that is required by Peruvian law before filing a lawsuit of its own.

Repsol said Refineria La Pampilla believes the shipowner’s claims that it suffered damage in the situation are “groundless”.

The dispute between the oil company and Fratelli d’Amico is just one battle in a swirling legal war.

In August, the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property of Peru, a government authority known as Indecopi, won a court’s green-light to proceed with a civil lawsuit for $4.5bn in compensation against a list of defendants that include Repsol and Fratelli d’Amico.

Also listed as defendants in that case are insurance giant Mapfre and Tanstotal Maritima, a shipping agency controlled by Chile’s Ultramar.

The lawsuit seeks $3bn in direct damages and $1.5bn in compensation to consumers and others impacted by the spill, according to Repsol’s annual report.

Repsol’s and Mapfre’s subsidiaries have challenged the lawsuit, arguing that the case lacks “due cause” and suffers from several other problems, including improperly accumulating petitions and failing to identify claimants.

They also argued that the government institute does not have the right to demand payment, and the lawsuit was filed while investigations had yet to establish civil liability, according to Repsol’s account of the proceedings.

“Although the lawsuit filed by Indecopi may entail a long process, Repsol reaffirms its assessment that, according to the criteria of the external lawyers and in view of all the opposing arguments put forward, the Peruvian courts will finally dismiss the lawsuit, and therefore considers it a remote risk,” Repsol said.

Repsol’s Peruvian refinery unit and Mapfre were successful in fighting a lawsuit by an association originally made up of more than 10,000 claimants affected by the spill seeking PEN 5.13bn ($1.36bn) in compensation.

After Refineria La Pampilla argued that the association lacked standing to sue and that its lawsuit should be thrown out for failing to identify claimants, the group reduced its claim to just PEN 21.9m, with only 353 remaining members.

A judge ultimately threw out that lawsuit and an appeals court affirmed the decision in June of last year.

But in December, the nonprofit group Stichting Environment and Fundamental Rights launched a new lawsuit in the Netherlands on behalf of more than 35,000 parties pursuing £1bn ($1.27bn) in claims.

“The defendants will assert that there is a lack of connection between the Dutch jurisdiction and the spill in Peru and, among other arguments, will highlight the similarities of this claim with that of the association (already dismissed) and, therefore, the multiple defects of form and substance of the claim, which allow it to be considered a remote risk,” Repsol said.

Repsol is also facing what it described as sanctioning actions from a variety of Peruvian agencies.