Ecotoxicity damage running to €680m ($732m) has been caused by the use of scrubbers on ships, a study claims.

Researchers at Sweden’s Chalmers University of Technology argue that exhaust gas cleaning systems and the discharge of their scrubbing water between 2014 and 2022 has polluted the sensitive Baltic Sea.

They claim that the discharges in the Baltic have contributed to an increase of certain pollutants by up to 8.5% in waters that already suffer from eutrophication.

They also argue that the environmental cost pales when compared to the economic benefits by shipowners who have earned back their investment in the scrubber installation through using cheaper, but more polluting, heavy fuel oil instead of more expensive, cleaner marine gasoil.

This, they believe, should be taken into account in future regulations such as a possible ban on scrubber use or scrubber wash water discharges.

The authors note that scrubber water discharges have been banned in a number of areas around the world, and comment on International Maritime Organization guidance on scrubber water discharge.

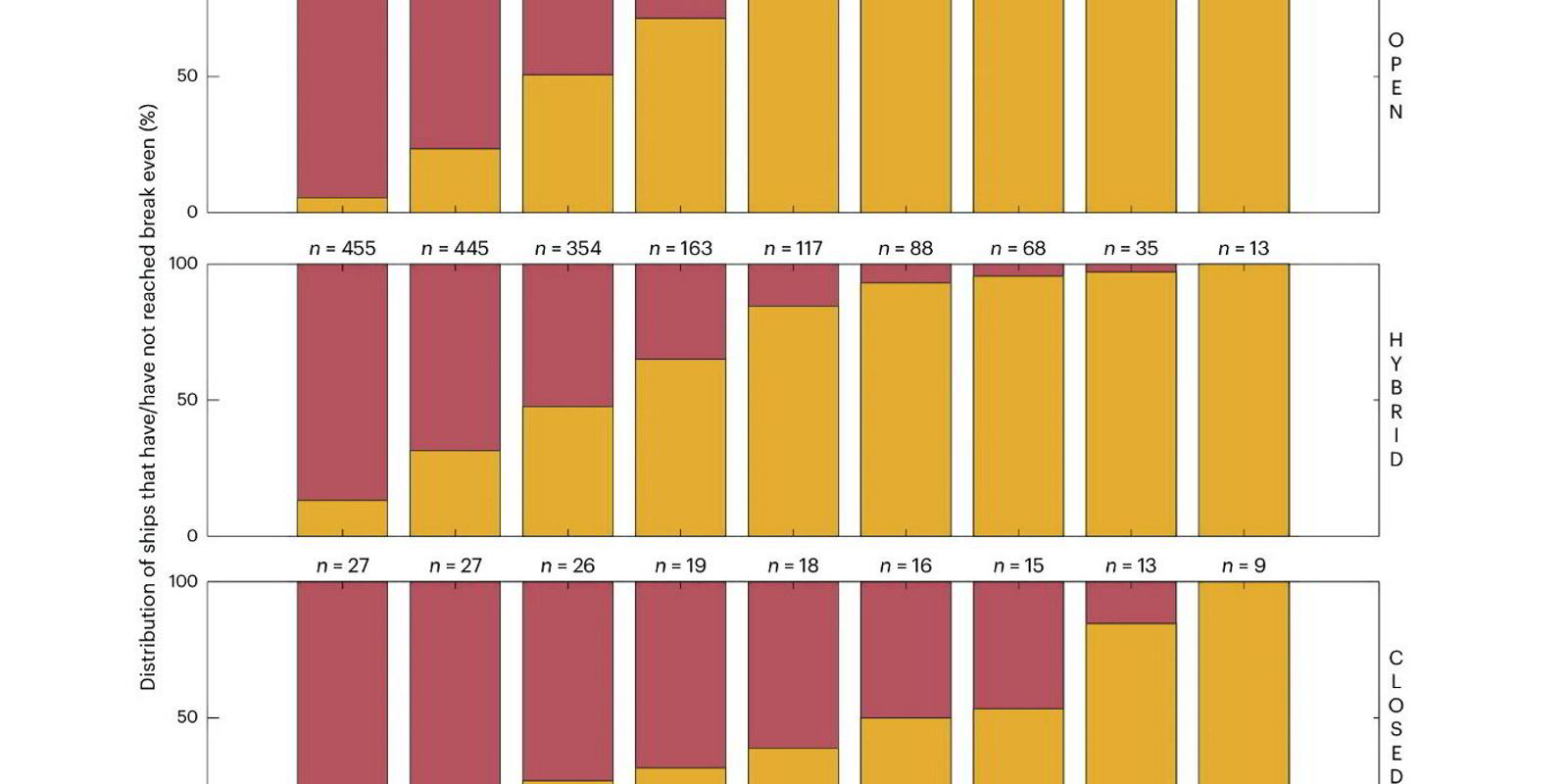

There are three types of scrubbers: open-loop, closed-loop and hybrid. Open-loop scrubbers are by far the most common.

The Chalmers study took in more than 3,800 vessels, 86% with open-loop scrubbers.

These systems draw in seawater and spray it through an engine’s exhaust, resulting in the sulphur oxides and particulate matter being captured. The used wash water is then discharged overboard.

The SOx gases react with the salt water to create sulphuric acid, according to the researchers, which is leading to increased acidification.

They estimate that during the eight years of their research, the discharge from open-loop scrubbers was about 10bn cubic metres per year.

The paper points to how quickly some ship owners and operators have been able to pay back the cost and investment of a scrubber and even profit from the price difference between high-sulphur residual oils and more expensive low-sulphur alternatives.

According to research calculations, most companies that invested in scrubbers have already reached breakeven, and the total savings made by the end of 2022 for all of the 3,800 vessels was €4.7bn.

“We see a clear conflict of interest, where private economic interests come at the expense of the marine environment in one of the world’s most sensitive seas,” said Chalmers doctoral student Anna Lunde Hermansson, one of the authors of the study.

The researchers want the issue to be given priority, with a discharge ban for Sweden’s territorial waters.

“From the industry’s point of view, it is often stressed that shipping companies have acted in good faith by investing in technology that would solve the problem of sulphur content in air emissions and that they should not be penalised,” added Lunde Hermansson.

“Our calculations show that most investments have already been recouped and that this is no longer a valid argument.”

The western Swedish port of Gothenburg already has a ban on scrubber water discharges in its port areas.

The open access research and study was funded by the Swedish Transport Administration, the Swedish Agency for Marine & Water Management and the European Union Horizon 2020 programme.