The future of the tanker market’s most important pillar appears to be hanging in the balance after China pledged earlier this month to become carbon neutral by 2060.

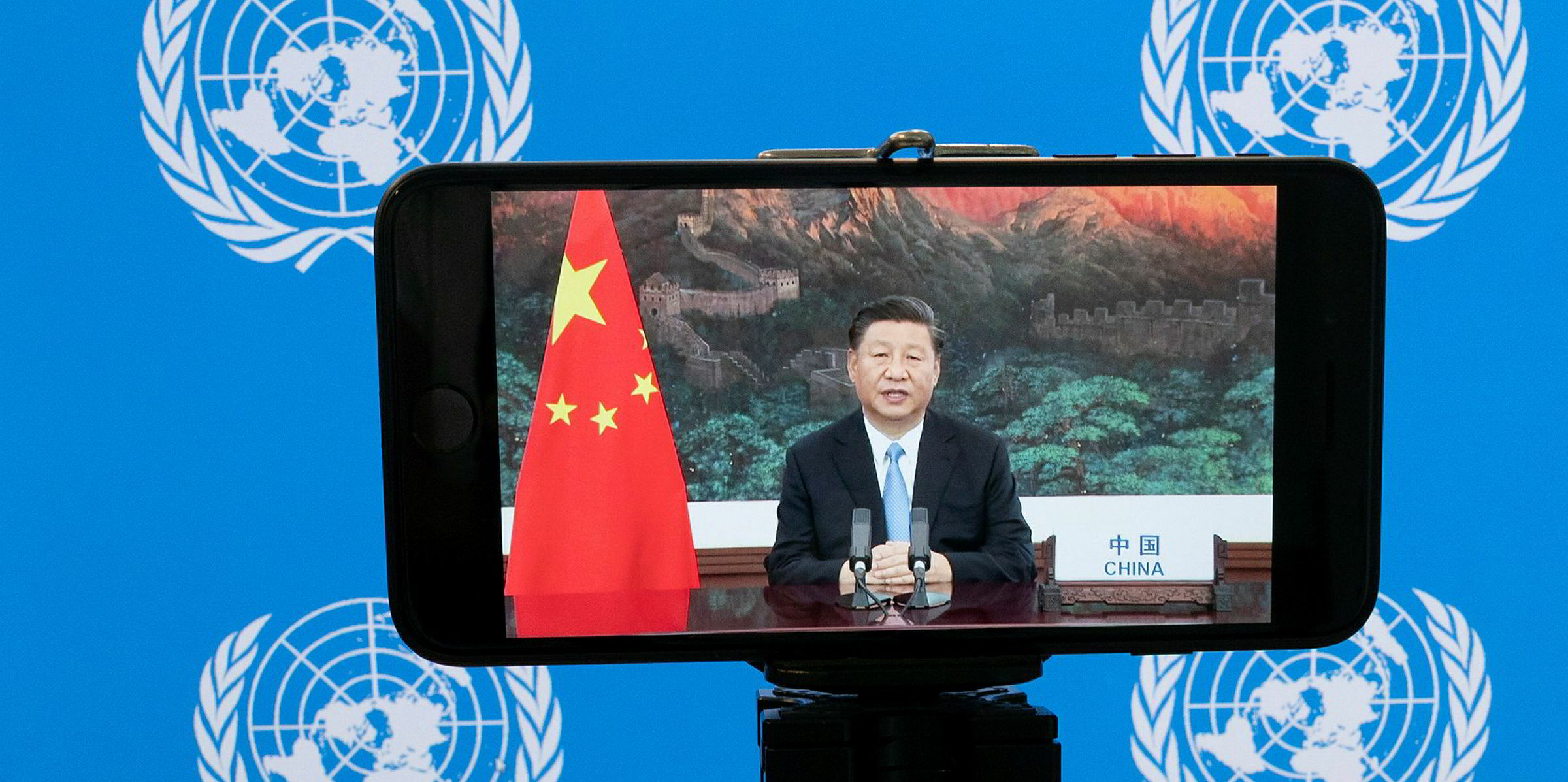

President Xi Jinping made the surprising commitment to showcase his country’s efforts in combating climate change at the United Nations General Assembly.

The powerful ruler — who is without term limits — also reiterated its goal for peak carbon emissions in the next decade.

At first glance, those targets could spell the long-term demise for oil shipping.

Dominance in tanker trade

The unabated growth of China’s crude imports has been the most important demand driver for the tanker market since the early 2000s.

Even the coronavirus pandemic is expected to put little dent in the world’s top oil importer’s demand growth — Clarksons Research expects Chinese seaborne crude to reach 500m tonnes in 2021, more than doubling its 2012 level of 245m tonnes.

In the same time span, global seaborne crude trade is forecast to only expand by 4.72% to nearly 2bn tonnes.

Moreover, China is poised to raise its exports of oil products and is emerging as one of the most important markets for product tankers.

Alphatanker estimates Chinese oil-refining capacity will expand by at least 3.29m barrels per day between 2019 and 2026.

AXSMarine believes China has the potential to become Asia’s largest product exporter and that its influence on the tanker trade will grow “exponentially”.

But China’s dominance in the oil and tanker markets is in conflict with its climate goals, assuming Xi is serious about cutting emissions.

The country is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and accounts for nearly 30% of global carbon emissions.

While 2060 is decades away, researchers believe China will need to reduce oil consumption as soon as is realistically possible to have a chance of meeting the pledge.

In its latest annual energy outlook, BP envisaged that China’s oil demand will need to shrink by two-thirds between 2018 and 2050 if global carbon emissions from energy use are to fall by 70%.

Geopolitical gesture

On the other hand, it remains to be seen what actions China will actually take.

Xi made the announcement as Beijing's relations with the West and some Asian countries continue to deteriorate, due to its border policies and human rights issues in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

Some commentators believe the pledges could serve as a nice gesture to the European Union and Democrats in the US, who have stated they would be willing to work with China on climate change.

Under Republican President Donald Trump, the US — the world’s No 2 GHG emitter — has rolled back its climate targets and refrained from setting a time frame to phase out carbon emissions.

However, while sending out the geopolitical message, China has launched a stimulus programme that could result in more emissions in the short run.

In order to revive the coronavirus-hit economy, it has relaxed restrictions on new coal power plants to create employment opportunities.

An S&P Global study has found local governments approved coal projects with a total capacity of 19.7 gigawatts in the first half of this year, the highest increase in recent years.

It is also uncertain how China defines carbon neutrality.

More than a decade ago, the country emerged as the largest supplier of UN-certified carbon offsets by developing clean energy projects under the Clean Development Mechanism. The offsets are sold to rich countries under the Kyoto Protocol to help them reach their emissions targets.

However, Chinese project developers were accused by many of rigging the system, with some projects said to be designed to cost little but have limited environmental benefits.

The EU eventually decided to ban the use of all UN-certified offsets in its Emission Trading System — the largest in the world — from 2013.

Looking for clues

To get a better idea on China’s proposed energy transition, many will look to the country’s next five-year plan due in March 2021.

If the country becomes more rigorous about its emissions, China's state oil majors — some of the world’s largest tanker charterers — may soon adopt different policy to select cleaner tonnage.

Major Chinese state-backed leasing houses — such as ICBC Leasing — could also be keener to sign up for the Poseidon Principles, joining Western banks’ efforts in building low-carbon shipping portfolios.

However, before Beijing is willing to provide more clues, Xi’s pledges will only provide more worries and few answers for shipping.