Japan's leading industrial conglomerates are beginning to put the brakes on ship production in the face of falling contracting levels.

According to the Japan Ship Exporters' Association, its members have a backlog of 26 million gt on order.

Preparing for slowdown

But 20.6 million gt of that will be delivered by the end of 2019, leaving yards with little more than five million gt of work to 2021, and little prospect of an immediate increase in orders.

As such, some of Japan's publicly-quoted industrial giants are repositioning themselves.

Kawasaki Heavy Industries has 11 LNG and LPG carriers on order at its main Sakaide plant, but only two ships are scheduled for delivery in 2020.

It has stated it will focus most of its production at two shipyards it co-owns in China with China Cosco Shipping Corp — Nantong Cosco KHI Ship Engineering and Dalian Cosco KHI Ship Engineering.

Similarly, Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding (Mitsui E&S)’s main Chiba yard looked like it would run out of orders in 2019 after the delivery of three VLCCs to Japanese owners.

But the company recently replenished its orderbook with three post-panamax bulkers with delivery in 2020.

Mitsui E&S has also forged a collaboration with privately owned shipbuilder Tsuneishi Zosen, under which it will produce ships at Tsuneishi’s lower cost plants in Japan, China and the Philippines. Mitsui E&S will contribute technical assistance.

If low-cost producers can work with technically advanced companies like ours, then we can survive

Mitsui E&S president Tetsuro Koga recently told financial news provider Diamond Online that the shipbuilder's advantage lies in its technical know-how rather than cost-competitive production.

Koga said: “We have thrown away the idea of being self-sufficient and we decided on that policy last year, which was our centenary year.

“Up to now, we have had a lot of advantages like brand recognition, technical capability and a wealth of technical personnel. As the long shipbuilding recession has continued, the competition to introduce newly developed ships has increased.

“But we have expensive facilities and cannot compete on cost. I think from now on each company must take advantage of their strengths and work with others to compensate for their weakness.

"For example, if low-cost producers can work with technically advanced companies like ours then we can survive."

Mitsui & Co has also signed a joint venture deal with Yangzijiang to build ships in China using Mitsui technology and know-how.

Passenger market

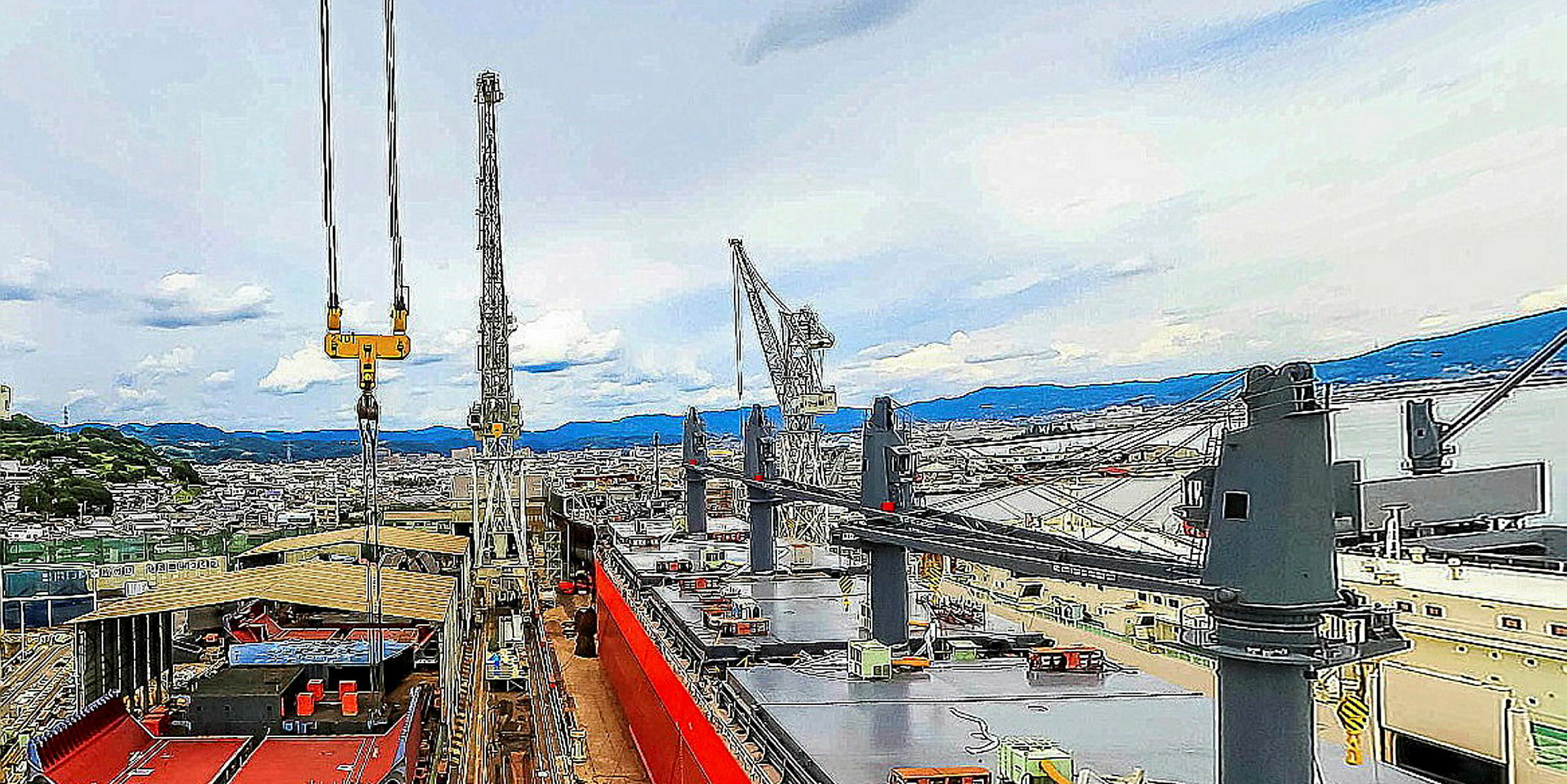

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, long considered the technical leader in Japanese shipbuilding, is seeking to compensate for a lack of merchant ship orders by building ropaxes at its main Nagasaki shipyard.

It has set itself a target of winning around $1.3bn-worth of work a year in the sector.

Mitsubishi believes it will have an edge in the market because it is an environmentally sensitive sector that requires advanced technical skills, such as producing high-efficiency, low-emission LNG-fuelled vessels.

The ropax market has traditionally been the stronghold of European shipbuilders, but many of the continent’s leading yards are full for the next five years building cruise vessels and Mitsubishi expects there to be room in the market for Asian yards.

However, Mitsubishi had a bitter experience attempting to break into the luxury cruise market, ringing up more than $1bn in losses while building two luxury cruiseships for AIDA Cruises.

So, after announcing it was chasing ropax orders, it tried to allay investors' fears of a repeat performance by publicly stating it would not enter the market "recklessly”.

Chasing technically advanced orders proved to be a disaster for Japan Marine United.

Its attempt to apply self-supporting prismatic type-B cargo-containment system technology — only used on small LNG carriers previously — to a 165,000-cbm LNG carrier has been a production nightmare.

The first in a series of four LNG carriers has been completed one year late with cost overruns and penalties, totalling around $800m in exceptional losses for the yard.

Privately owned yards

However, while Japan’s publicly quoted industrial giants appear to be struggling many of the privately owned more cost-competitive yards appear to be in better health at least in terms of the backlog.

Privately owned Onomichi Dockyard has 23 chemical and product tankers on order filling its orderbook through to the end of 2020.

The largest private shipbuilding group, Imabari Shipbuilding has orders into 2021 at its main Marugame, Imabari, Hiroshima and Saijo plants.

Oshima Shipbuilding has 63 orders for mostly ultramax and handymax bulk carriers with deliveries also running well into 2021.