Singapore has firmly established its place among the top nations driving change in shipping.

The innovation buzz permeates every corner of its maritime sector, and everyone involved will tell you it’s not by happenstance.

That innovation is an example of what happens when an entire maritime ecosystem comes together to find solutions to the challenges faced by the industry.

Everyone, from the government, through its regulator the Maritime & Port Authority of Singapore (MPA), down to the smallest harbour launch operator, is working collectively to solve the biggest challenge — meeting the International Maritime Organization’s 2030 and 2050 emissions targets through digitalisation and technology.

The MPA plays an active role in initiatives, frequently teaming up with the corporate sector on projects, from giving regulatory backing to providing scholarships and financial grants, to even joining as a founding partner and stakeholder.

First-hand experience

Some of its better-known initiatives are the maritime technology start-up accelerator PIER71, a strategic collaboration with the National University of Singapore; and the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation, a public-private non-profit partnership looking for pathways for decarbonisation and removing roadblocks.

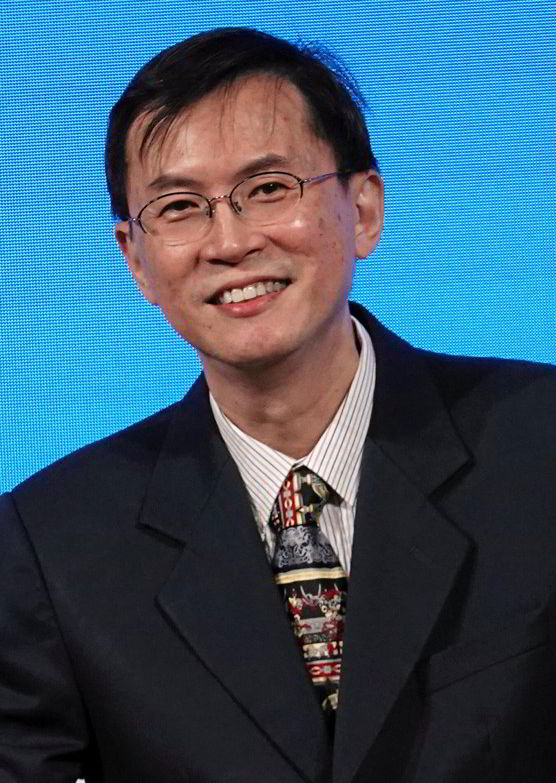

Kenneth Lim, MPA assistant chief executive for industry & transformation, said his organisation has evolved beyond being just a flag state, a port state and a port authority.

“We also see ourselves beyond a regulator to become also the developer and, therefore, encouraging and participating in many of that industry consortia to have a first-hand experience in what this new transition means,” he said at the Asia Pacific Maritime conference in March.

Lim said it is important for stakeholders participating in these initiatives to document what they have learned and what gaps have been identified: “If there are design issues, operation issues or procedural issues, then it needs a value chain effort to come together to solve some of these problems and challenges.”

Singapore, as one of the world’s top maritime hubs, needs to be an innovation driver, he added.

“Singapore is the fifth-largest ship registry in the world. We have crossed the 100m gt mark, so as a ship registry, we take it upon ourselves to make sure that we can improve all the ships that are registered under the Singapore flag by actively participating in the design of the ships and supporting our customers,” he said.

And as one of the world’s top bunkering ports, the country must also take on the responsibility of ensuring that its bunkering sector is ready for the future.

“Singapore adopts the position of a multi-fuel approach, so the port is getting ready for the bigger field,” Lim said.

“We need to make sure the bunkering operation is the safest and most efficient, thereby gaining all the standard procedures in methanol and ammonia, and then at the IMO level, sharing the experience.”

The government, through the MPA and investments made in the technology sector and infrastructure, has pumped millions of dollars into maritime innovation.

“This is the brilliance of Singapore — it’s about the big picture,” said Baldev Bhinder, managing partner of commodities and shipping law firm Blackstone & Gold.

“There are so many ways that Singapore spends today for an invisible return tomorrow. Some of these initiatives may pay off in the long run, and some may not — but the whole exercise is a masterstroke of creating Singapore’s image as a hub of innovation.

“The problem with so many of us, whether as individuals or companies, is that we ask what’s the immediate return, myopically focusing on the first dollar rather than intangible benefits.”

This is where classification societies can play a key part. These organisations are tasked with assessing and certifying ships for compliance with safety, environmental and operational standards, ensuring safety, reliability and regulatory adherence.

They certify compliance with rules as regards type, construction, equipment, maintenance and surveys of ships.

Cristina Saenz de Santa Maria, DNV’s Singapore-based vice president and regional manager for maritime in South East Asia, the Pacific and India, believes classification societies have an important role in driving shipping innovation.

DNV is one of many leading classification societies that have established major bases in Singapore and are driving innovation by participating in the initiatives and projects emanating from the country.

“There is so much that is new being adopted, ranging from new technologies to alternative fuels that need to be tested, trialled and deemed safe,” Saenz de Santa Maria said.

“The industry has already talked a lot. It’s about piloting now, testing and showcasing what the industry needs. And from the class societies, what they need is assurance that, from the safety standpoint, whatever solution you are adopting or testing can be viable.

“Should an accident happen — let’s say, for example, with an LNG or ammonia-fuelled vessel — it would be detrimental and move us, the whole industry, back quite a lot.”

DNV invests 5% of its revenue in innovation, research and development, and has large testing laboratories in several global locations including Singapore, where it recently added a hydrogen testing facility.

“Hydrogen is very relevant. It is being talked about much more in the industry as a source to help decarbonise, so hydrogen testing will contribute to innovation from the assurance side, to move the needle and make sure that the industry progresses in a safe manner,” Saenz de Santa Maria said.

DNV set up its Maritime Decarbonization & Smart Shipping Centre of Excellence in 2021 and is a founding member of the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation.

It is also a partner in Studio 30 50, an industry-led start-up incubator launched in 2023.

Saenz de Santa Maria details a long list of local innovation and decarbonisation projects that DNV has been involved with, from additive manufacturing (digital printing) and artificial intelligence technology to ammonia bunkering and battery-powered vessels and associated infrastructure.

It has worked with industry stakeholders, product developers and regulatory authorities on establishing new maritime processes, standards and frameworks.

This testing of technologies — or technology qualification, as class societies call it —is very relevant, especially for the start-up costs system, she said.

“There are a lot of start-ups that just focus on one solution. What they need to succeed is an independent third party that can back them up and prove this technology, whatever it is related to, is safe to use,” she explained.

Saenz de Santa Maria also said the role of classification societies has evolved beyond just testing to make sure new technologies are safe. They must now act as consultants.

DNV not only evaluates new technology from an engineering technology perspective, but it also evaluates the commercial aspects of the technology.

“Our advisory team assesses the commercial applicability of all these new incoming technologies, which goes hand with techno-commercial studies with market forecasts that we have mapped out in certain cases,” she said.

“We look at the whole supply chain from a cost perspective and see if it is feasible or not. I think that having a pragmatic approach from the commercial side is important because they need to make sense from a business perspective.”

This, she said, is a class society’s way of helping to drive innovation.