When Sam Norton took the helm of Overseas Shipholding Group in 2016, the company had exited bankruptcy and spun off the international-flagged tanker fleet that represented most of its business.

As the OSG chief executive recalled in an interview, chairman Doug Wheat had asked him to set up a management team, “figure out what to do” with what was now a pure-play US-flagged tanker company and position the New York-listed shipowner to be sold.

Delivering a sale ultimately took eight years, a time that saw the company ride a rollercoaster that included punishing Jones Act markets during the Covid-19 pandemic followed by a boom that took OSG shares to record heights.

The 10 July takeover by Saltchuk Resources marks a key milestone in a career that has seen Norton play the roles of banker, Ofer family lieutenant, container shipping entrepreneur and now the leader of OSG in a new phase under private ownership.

It was a path with significant challenges, including shutting down shipowner SeaChange Maritime amid tough boxship markets that would not see a boom until it was too late.

“Each transition pushed me … to understand risk in different ways and to be able to tolerate risk in different ways than I would have ever thought conceivable looking backwards,” he told TradeWinds.

Chinese-language studies

Norton took a circuitous path to shipping that began when he was a student of Chinese language and literature at New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College in the late 1970s.

In a bid to take his language skills to a new level, he participated in an immersive language programme in Taiwan, undeterred after the US State Department pulled its funding when President Jimmy Carter recognised Beijing, rather than Taipei, as the government of China — a move that sent the island into a recession.

1981: Chinese language and literature degree from Dartmouth University

1984-1988: Lead role in the Asian distressed assets group of the First National Bank of Boston

1989-2005: A senior executive officer at the Sammy Ofer Group’s Tanker Pacific Management

2006-2016: Co-founder and chief executive of SeaChange Maritime, a container ship owner

2014-2016: Non-executive director at OSG

2016: Senior vice president at OSG, where he was president and chief executive of the US-flagged business until the company was divided

2016-present: Chief executive of OSG

After graduating from Dartmouth, Norton decided to go to Taiwan to work while continuing to study the language. While there, he joined the First National Bank of Boston whose general manager in the country was also the only other American working in the branch.

Starting as a freelancer and earning what he described as beer money, Norton was tasked with helping correct the English-language memos and proposals of Chinese-speaking employees.

“I quickly figured out this was an inefficient way to do things because the Chinese guys and women were spending hours to write something that was OK, but it needed a lot of work,” he told TradeWinds over breakfast at a cafe near his Miami home.

“I said, ‘There’s a better way to do this’.”

Norton asked bank staffers to tell him what they wanted to say in Chinese, and he translated it into English, which became an opportunity for him to learn the language of business and receive an education in banking.

Appreciating the results of his work, the bank employees began taking Norton on calls to factories that were borrowing from the bank.

His boss began offering to pay Norton to buy books, another opportunity to continue his self-education in banking.

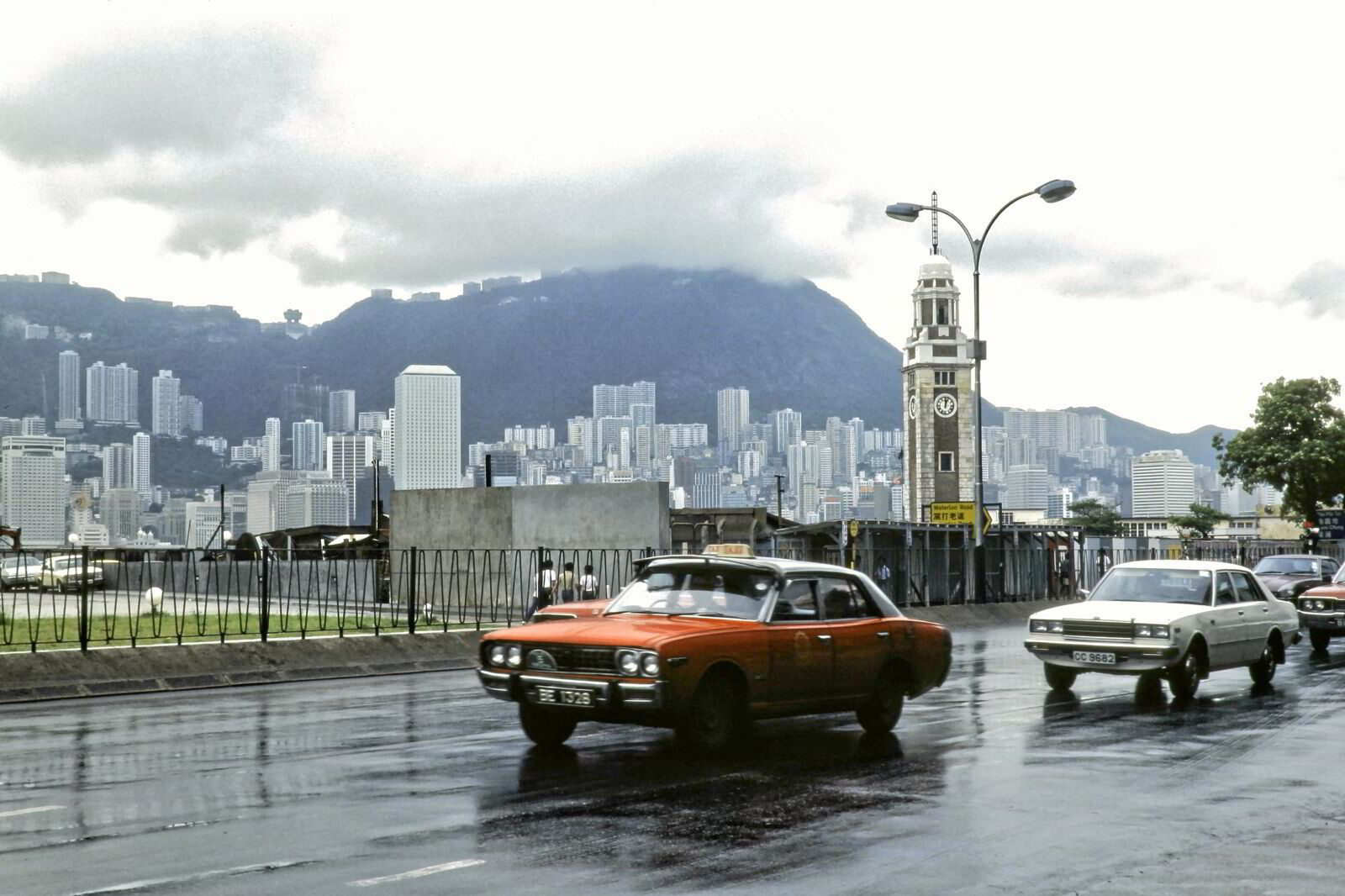

Hong Kong banker

Eventually, the bank — then one of the biggest in the US — sent him to Boston for its loan officer training programme, followed by a job offer in Hong Kong.

“Then I became a real employee of the bank with a title,” Norton said.

But just as he started in 1984, UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher agreed to hand the island territory back to China, sending the economy into recession and First National’s loans into trouble territory.

Norton’s first job in banking quickly became an expertise in distressed loans, or workouts.

“I was working with textile companies and real estate companies and various that couldn’t pay their loans, and trying to figure out how to restructure,” Norton recalled.

“There’s no equivalent of Chapter 11 in Hong Kong, so it was either liquidate or figure out a way to string them along and gain leverage.”

A year later, it was the shipping companies that were in financial trouble. The industry descended into a global crisis that compounded when an international currency agreement, known as the Plaza Accord, doubled the value of the Japanese yen versus the dollar practically overnight.

Many shipping industry loans, particularly in Asia, were priced in yen at the time.

“And then liabilities doubled overnight, and virtually all the equity of all the shipping companies in Asia disappeared,” Norton said. “And so it became a huge workout situation.

“My boss came and said, ‘Forget about the textile companies. You’re going to be working on shipping companies’.”

As a leading member of the First National workout team, he spent that time sitting on creditor committees for companies that were restructuring, liquidating vessels and arresting ships.

During this period, Norton became acquainted with Idan Ofer, the son of shipping billionaire Sammy Ofer, who was then based in Hong Kong and hunting opportunities amid the financial distress.

“We were kind of swimming in the same pool at the time,” Norton said of the Ofer scion.

“He was trying to work with the banks to take over the management of ships that banks had foreclosed on.”

Ofer Group lieutenant

Norton said he and Idan became friends, and the banker was invited to join the Ofer group.

He began with Tanker Pacific Management — today known as Eastern Pacific Management and controlled by Idan — in 1989.

That same year the Tiananmen Square massacre sent shockwaves through the Hong Kong shipping community, and, in 1990, Sammy Ofer moved the headquarters of his empire to Singapore, beginning Norton’s 24-year stint in the country.

For the banker turned shipping executive, the group was what he described as an “amazing” education.

He cited the Ofer family’s emphasis on understanding every element of the shipping business and on the notion that “very little value is derived, other than through luck, in trying to predict the market” and what the future may hold.

“The most successful shipowners and ship operators understand that [shipping] is a commodity and that the low-cost provider is going to succeed over time because if your cost structure is $1 less than your competitor, that’s $1 in free capital that you’ve generated in competition with your competitor,” Norton said.

In practice, what the Ofer philosophy means is to be hands-on as a manager and understand how everything works on a ship, the executive explained.

“You need to do that so you can understand where the money goes and how to control it, so you can keep your cost down,” he said.

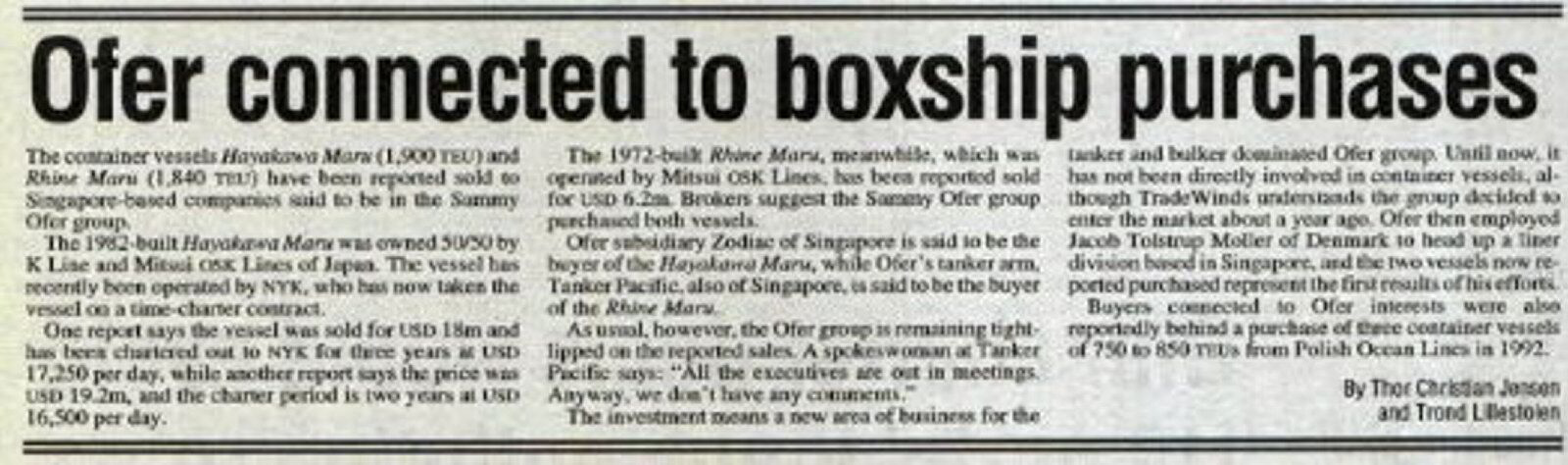

Among the highlights of Norton’s tenure at the Sammy Ofer Group was his leading role in moving the company, which was then focused on tankers and bulkers, into the container ship space.

In 1995, Idan recruited young shipbroker Jacob Tolstrup Moller, who had worked at Barry Rogliano Salles, and then asked Norton to oversee the new boxship division.

They began buying up 1,500-teu to 2,000-teu vessels, which were large, at the time, before container shipping activities were moved to London near the end of the decade.

Idan and brother Eyal Ofer, who divided the family empire after their father died in 2011, are both major owners of container ships.

Norton also led the group’s entry into another sector — floating production, storage and offloading units — with the founding of Tanker Pacific Offshore Terminals, which later became Omni Offshore Terminals.

In 2004, Norton decided it was time to move back to the US, relocating in 2004 to Miami, where he continues to live, dividing his time between Tampa, the Florida city where OSG is headquartered.

Container shipping entrepreneur

After amicably parting ways with the Ofer group in 2005, Norton teamed up with a Miami-based former co-worker, Yariv Zghoul, with a plan to launch a container ship-owning business focusing on chartering ships to line operators in regional trades.

After raising cash to start SeaChange Maritime, they seemed to have had good timing, making most of their purchases after the 2008 financial crash.

“We were following the playbook of buying ships when they’re cheap. Eventually, the market turns around and the market comes back, and if you can keep your costs down, that’s how you make money,” he said.

“The problem was the container market collapsed and then never came back.”

After a decade of tough markets and a charter dispute with the US Navy’s Military Sealift Command left it with a heavy debt burden, SeaChange Maritime began winding down its operations in 2015 and 2016, although Norton said the company did ultimately win $7m in its court fight with the government.

The SeaChange Maritime experience represented a key moment in the evolution of Norton’s growing appreciation for risk tolerance.

“SeaChange was pretty much the pinnacle of that, because there will be weeks where we didn’t know how we were going to make payroll, frankly, and I learned to just accept that,” he said.

“I didn’t freak out. Stress didn’t kill me. I just figured we’ll just work, and if we solve the problem, that’ll be good, and if we don’t, well, you know, we’ll figure out something else.”

That is because anyone who claims to know what will happen in the next six months is a liar. Events can change markets overnight, said Norton.

It was a lesson that would be key to his next major challenge.

OSG leader

After Wheat tapped Norton to lead OSG in 2016, where he had served on the board since 2014, the tanker owner faced oversupplied Jones Act tanker and articulated tug-barge markets — not exactly the time to lock in the sale that was hoped for.

But things looked better in 2019, and OSG tapped Goldman Sachs to attempt a deal, approaching private equity firms.

Norton said that New York alternative investment firm Stonepeak made an offer, but OSG’s board of directors felt the bid undervalued the tanker owner.

Then markets again got in the way of finding a buyer, as the Covid-19 pandemic clobbered the domestic tanker markets that would not take their significant upward turn until Russia invaded Ukraine two years later.

Norton attributes OSG’s ability to survive to having the conviction to change plans quickly and be decisive.

“The analogy that I gave to people was that we have a bottle of water and a desert that we have to cross. We don’t know how long that desert is, so we have to marshal our water to get us to the other side,” he said.

“And that means we have to save as much cash as we can. That’s the only strategy that can get us to the other side.”

The company made tough calls, like laying up seven vessels, which some thought was a radical strategy. During the trough, Saltchuk offered to buy OSG for $3 per share in 2021 but pulled it back. (The Seattle maritime conglomerate would ultimately pay almost three times that price.)

Wheat, who remained OSG’s chairman until the Saltchuk deal closed, said many at the company could have jumped ship in such tough times.

“They decided not to [jump ship] because of Sam’s leadership and would have followed Sam to the ends of the earth, I have a feeling,” he told TradeWinds.

“That’s what usually makes somebody a very good CEO and leader: how much people respect him.”

Read more

- Takeovers and tragedy: How new OSG owner built a multibillion-dollar shipping empire

- Sam Norton to continue at OSG helm after Saltchuk takeover, executive confirms

- Saltchuk seals $950m OSG takeover after two-thirds of investors tender shares

- Private party: Overseas Shipholding Group joins parade of shipping companies exiting capital markets

- Key window into Jones Act tanker market closes with $950m OSG takeover