Fireworks could be heard exploding in the background as Ardmore Shipping executives prepared to close the purchase of six medium-range tankers from John Fredriksen’s Frontline.

The $172.5m deal in the summer of 2016 was the largest secondhand transaction in the Irish company’s history — supported by a $64m equity issue at a time when many experts believed the capital markets were closed to shipping.

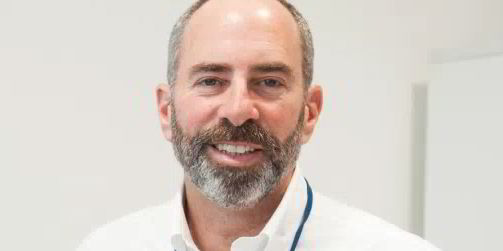

“I made the joke that it was the first deal we ever did in Greece, because everybody we were working with was in Athens,” explains Ardmore chief executive Tony Gurnee, remembering a go/no-go call to close the deal during Posidonia week. “Apparently a lot of people on the call were at the Clarksons Posidonia party.”

While the industry at large was enjoying Greek hospitality — and Fredriksen was fishing in his native Norway — Gurnee and his team were completing a transaction two years after the first discussions had taken place.

“We actually inspected those ships while they were still under construction and really liked them. We fully vetted them early on and it was a matter of just finding the right formula,” Gurnee tells TW+ in the boardroom of Ardmore’s modern office in central Cork, overlooking the south channel of the River Lee.

“That was an example where we were able to move quickly when we saw an opportunity. We had been in discussion on those ships for two years. Obviously they evolved over time and we had to wait for the right moment to execute.

“We always try to do business in a way that if things do not go to plan, you can always come back to it on good terms. We did that several times with those ships. It probably also helped that we had a working relationship with Frontline commercially.”

Last summer’s swoop may have been Ardmore’s most eye-catching deal, but it was by no means its only foray into the sale-and-purchase market since the company came to the industry’s attention in 2010 under the low-key TradeWinds headline “Gurnee starts tanker outfit”.

Ardmore, which was launched with the backing of private-equity transport specialist Greenbriar Equity Group, has bought 16 secondhand vessels and ordered 14 newbuildings since 2010.

While its deals may appear to be getting progressively larger on paper, Gurnee says the company is “happy to buy ships one at a time again — and will”.

“Good performance starts with good ships,” he adds. “If you start with ships you are not happy with strategically, technically or commercially, it’s very hard to recover from that.”

The desire to buy the right vessels at the right time kept Ardmore on the drawing board for almost a decade after Gurnee and Greenbriar founder Reg Jones first discussed starting a shipowning venture. The pair (who worked together on the Teekay Shipping IPO of 1995) initially looked at opportunities in the early 2000s but by 2003 felt the market was running away from them and opted to wait.

They stayed on the sidelines through the boom years of the mid-to-late noughties and only when the music stopped after the financial crisis of 2008 did they sit down together again.

“By early 2010 we felt it was the right time to start,” Gurnee recalls. “By that point we had done a lot of work and decided we liked the medium- and long-term outlook of the product tanker sector the most. We had a fairly clear plan right from the start and, given I had a background in chemicals, we decided to make that part of the mix as well.”

Gurnee says the most important early step was hiring “some great people”. Chief operating officer Mark Cameron was located via a network of friends, and finance chief Paul Tivnan was brought on board from Ernst & Young (EY) in Dublin.

“Our very initial discussions were more philosophical than practical. What kind of company would we be proud of? What did we want our legacy to be? The rest of it was really instinctive in terms of who we were and what our experience had been professionally,” Gurnee says.

With asset prices thought to have reached a bottom in early 2010, Ardmore made its first acquisition, buying the 45,000-dwt Zao Express (built 2004). It was renamed Ardmore Seafarer, becoming only the fourth vessel in the world at that time to have seafarer included in its name. Gurnee says the choice was deliberate, reflecting the importance the company placed on its crew — a value he and Cameron absorbed during their separate careers at Teekay.

More additions quickly followed and by the close of 2010 Ardmore had added further secondhand tonnage and placed its first newbuildings at SPP in South Korea.

Over the following two years — which saw peers Diamond S Shipping buy the Cido Shipping tanker fleet and then Scorpio Tankers amass a vast stable of newbuildings — Ardmore continued to grow steadily. “I used to joke that others were just buying 30 ships at a time and we were building a business the low-brow way: one ship at a time,” Gurnee says.

By early 2013, with six ships on the water and four under construction, Ardmore spotted an opening in the US capital markets and moved for an IPO. Gurnee says he had no illusions when entering the process. He had been chief financial officer when Teekay failed with its first listing attempt in 1994, an experience he describes today as “horrendous” but his “most valuable capital markets lesson”. The Canadian owner succeeded at the second attempt to go public in 1995.

The combination of Gurnee and chairman Jones (a former Goldman Sachs banker who was instrumental in taking Teekay Shipping to Wall Street) at the head of Ardmore meant an IPO was from the outside considered to be on the cards for the tanker owner. However, floating the company was not at the top of Ardmore’s to-do list when it was formed.

When the call was made to go public, it was the shipowner, not its core investor, that drove the process. Tivnan explains: “There are two types of IPO: the exit for private equity investors and the opportunity to build and grow. We were definitely an opportunity to build and grow. Greenbriar were 2½ to three years into their investment at that point, so it was never a question of exiting.

“It was a question of ‘what can we do to add incremental value to the business; what will make their shareholding even more valuable?’ The share price is what it is, but we have grown and over the period that we have been public there has been opportunity there to create real value. It was still absolutely the right decision but for us it was an opportunity to create, build and grow.”

In early 2013 the share prices of public products tanker owners were going up and newbuilding prices were heading down. “It was a perfect combination, and to Paul’s credit he had done about a year’s worth of prep work. He always had that idea and we were ready to move. We ended up getting it done very rapidly,” Gurnee says.

As would later be the case with the 2016 follow-on offering, Ardmore sought to list at a time when the US capital markets were not receptive to shipping. Indeed, it was looking to become the first successful IPO stateside since Box Ships almost two years earlier.

Gurnee laughs at the suggestion that he and his team kissed the legendary Blarney stone — which is built into the battlements of nearby Blarney Castle and reputedly bestows the gift of eloquence on those acrobatic enough to kiss it — to aid communication with investors.

“I think the key to our success was to be able to move very, very fast, being prepared, being able and willing to work all the hours it took,” he says. “It’s really like a champion sports game. We went all-out until the whistle to get it done.”

As Ardmore looked to close the initial offering in August 2013, the team encountered a stone of a different kind. It was placed on its road to Wall Street by Scorpio Tankers and UBS investment bankers Simon Smith and James Palmer in the form of a competing $190m equity offering.

“At the time I think emotions were running fairly high,” Gurnee recalls. “I don’t think they did anything wrong. We are all charged with running our businesses and creating value for our own shareholders. So we might have been pretty steamed up about it at the time but we are not now and we actually get along with them quite well. I think everybody has got to sell their own story and do the right thing for their own company. We were able to get it done and we were very happy.”

Ardmore stock priced below the initial range, but the shares were still printed at a premium to net asset value and the company collected $140m from the IPO just a month after celebrating its third birthday. “What is interesting is that there was still enough capital for both companies,” Tivnan points out. “They were both very sizeable transactions in a two-week period and it probably speaks for the strength of the capital markets in that pocket in time.”

As TW+ spoke with the Ardmore executives, products tanker peers Torm and Hafnia Tankers were still waiting to fulfil long-term ambitions and join Ardmore and Scorpio on the New York Stock Exchange. Gurnee would welcome their arrival.

“People have a misconception that capital is scarce,” he says. “The US market cap for equities is in the trillions. There is plenty of capital. You just have to have a good company. There is plenty of room for everybody. What we hope is that we would like to be in good company in terms of the companies that are able to go public.”

Despite being headquartered in Europe, Ardmore did not seriously consider the London or Oslo stock exchanges. “I think they preferred our accents in New York,” Gurnee says. “Joking aside, there are many paths to performance in this business. Some have done very well by listing in Singapore or Amsterdam or Oslo. Our orientation has always been towards North American capital markets. That certainly was Greenbriar’s comfort zone. It’s my comfort zone. Paul had worked with US-listed companies when he was at EY. When it comes to the equity side of the business, we have always had an America orientation.”

Tivnan adds: “New York, in terms of the industrial companies, is still the premier stock exchange in the world. All the others hold their own for different investor bases, but the vast majority of our investors are US funds, mutual funds and pension funds. The natural home for that type of company would be the New York Stock Exchange.”

In 6½ years, first as a private and then as a public vehicle, Ardmore has grown from a blank sheet of paper to one of the world’s largest products tanker companies.

Gurnee says the expansion did not feel fast from the inside, nor was it executed at an even pace. “We tended to take a big step forward, absorb where we were at that time, build systems, hire people, create teams to really optimise and get really good at what we were doing at that time. And then, when we felt we were at that point, we were ready to make the next step. That, combined with being ready for opportunity.”

In an interview with TradeWinds in early 2011, when the company was in its infancy, Gurnee said his interest was in building a “real business”, shredding a common retort of the time that Ardmore was a “vulture fund”. Today Gurnee believes Ardmore, which now has operational bases in Houston and Singapore, is “not dissimilar to Teekay in the 1990s”.

“As you go through life you tend to go back to what you know and what you are comfortable with,” he says. “[Ardmore is] very efficient, very focused, very commercially driven but has a great operational platform as well. They were focused on aframaxes, we are focused on MRs. Obviously, every company I have ever worked for, and I think it’s the same for everybody around the table here, you always learn a lot of good lessons and a lot of lessons that were learned the hard way.”

As for the future, Gurnee says the owner does not have a succession plan. But he believes the future is sitting around the same boardroom table, with Thomas Hodgson, senior vice-president of planning and corporate services, and senior director ¬¬– chartering services Gernot Ruppelt present along with Cameron and Tivnan.

“One of the hallmarks of solid companies that are able to evolve, adapt and succeed is they build talent within,” Gurnee says. “I think we have a lot of talent.”

Winding the clock forward five years, he predicts Ardmore will either be “a little bigger or a lot bigger, but not the same size” as it is today.

“We will have been focusing on ways to improve performance. One of the important parts of that, operationally, commercially and to a certain extent financially, is scale. But you need to do it for the right reasons, at the right time and with the right ships. We will probably be more of the same and quite a bit further on in terms of performance,” he says.

“We love the MR sector because it’s such an enormous sector globally. There is plenty of scope for growth. We are building some very effective trading capabilities and it’s one of the best shipping sectors to be in from a trading standpoint.”

From New York to Cork: ‘It’s a bit of a contrast’

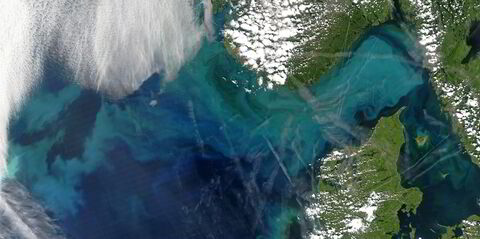

Statio Bene Fide Carinis reads the Latin inscription on Cork’s coat of arms on the front of the city’s old customs house — “a safe harbour for ships”. It is one of many historic maritime connections for the city, which long ago saw vessels come up the River Lee and into its heart.

Cork’s famously high-quality butter was shipped as far afield as the West Indies and it was from Ireland’s second-largest city that Annie Moore sailed on the steamship Nevada in 1892 to become the first person processed at the Ellis Island facility in New York.

American Tony Gurnee, who started Ardmore Shipping in Cork in 2010, initially moved to Ireland with his family when he was 12. “Back in the dark ages,” he jokes. “I more or less grew up here, went away for a long time, joined the US Navy, saw the world, then got into banking and shipping.”

He returned around 10 years ago with his Danish wife “to give our kids an international experience and have a bit of fun”.

When Ardmore was launched, Gurnee was willing to go anywhere in the world. A return to New York, and bases in London, Rotterdam and Amsterdam were all viable options.

However, Ardmore’s sole shareholder at the time was Greenbriar Equity Group, which had extensive experience of Ireland as a location for financial leasing in the aviation industry. “They said, ‘We are very comfortable with Ireland; if you want to stay there, go ahead’. That is how it all began,” Gurnee recalls. “We have been able to attract really terrific people. That’s the most important reason. There is no tax angle. Being an hour from London is key.”

Mark Cameron, the Irishman whom Gurnee recruited from Teekay as Ardmore’s commercial chief, adds that the work-life balance is also an important component. “You are able to get something here that you are not able to get in London,” he says.

Gernot Ruppelt, senior director ¬– chartering services, a former Maersk man, believes Cork, a city of 126,000, provides an escape from the industry “noise” in New York, London and other hubs. “New York to Cork is a bit of a contrast,” he says. “But I think you can be where you need to be very easily and you don’t need to be on the doorstep all the time.”

Gurnee draws parallels with Teekay’s location in Vancouver, Canada. “I know [founder] Torben [Karlshoej] felt it more beneficial to be somewhere you can just focus on your business and not be in the middle of all the traffic, communication and competing companies,” he says.

Taking the positives from a negative

Tony Gurnee and Ardmore Shipping chairman Reg Jones initially met in 1992 and their first encounter failed to secure a deal. Gurnee was the chief financial officer of Teekay, which was in distress following the death of founder Torben Karlshoej.

Gurnee had heard the high-yield market was opening up and saw an opportunity. “We went to see a bunch of banks, including Goldman Sachs, where Reg was working,” Gurnee tells TW+.

“I remember going into a conference room with him and then spreading all of the financials out on the table, explaining to him that the founder had just died, we did not have audited financial statements but if you put all this together in a certain way it’s going to be a great company. He said, ‘I sympathise with you, but that is just not the kind of business that Goldman Sachs does’.”

Despite the initial rejection, that meeting was to mark the start of a long-term business relationship. “I don’t mind no. You always learn from the no,” Gurnee says.

“They passed on the first deal and we ended up doing the high-yield issue with Morgan Stanley, which was a big success and got the company moving in the right direction. Then I think Goldman Sachs was much more interested in us. So we developed a relationship on an investment banking basis.”

After a first IPO effort failed in 1994, Gurnee and Jones teamed up when Goldman Sachs helped Teekay Shipping list in New York the following year.

“Reg was always terrific at giving strategic advice as well as on capital markets,” Gurnee says. “In fact, he does that for us today. We are very privileged to have that kind of a mind involved in the company to help us out with those kinds of decisions.

“Eventually, Goldman Sachs was our choice to take Teekay public in 1995. We did another bond issue and even after I left he continued to do a lot of work for Teekay until he left Goldman in 2000.”

Today, Greenbriar, the private equity company founded by Jones, is Ardmore’s largest shareholder with a 17% stake.