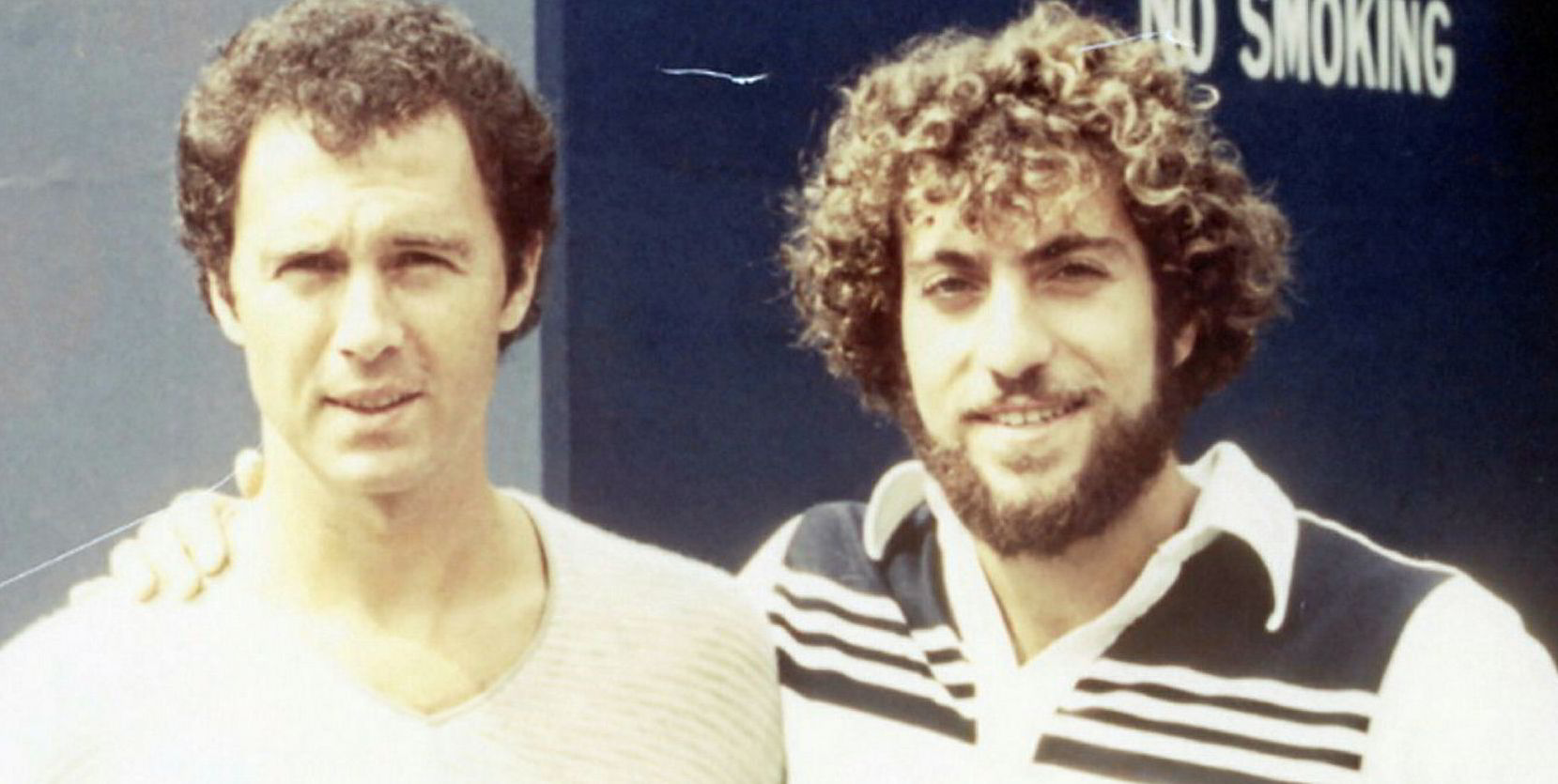

James Christodoulou has always been more than the guy most likely to crack your ribs with an over-exuberant bear hug at Posidonia.

Beneath the burly, hyper-gregarious exterior of a former professional soccer player has resided a thoughtful observer of shipping and the money behind it, from his days as the first chief financial officer of Peter Georgiopoulos’ General Maritime in 2001.

But the New Jersey-born one-time “IPO King” is now living the dream in Miami as president and chief operating officer of a provider of charging stations for electric cars.

Wait, electric cars? So Christodoulou is no longer a shipping guy? He frowns when the thought is mentioned.

“Nobody ever leaves shipping,” he says, his eyes locking in an intense gaze across the table. “You just primarily focus on other things. I’m just primarily focused on this now.

“But the home page on my computer is and always will be TradeWinds. You’re constantly working on things in and around shipping. Once you’re in shipping, you’re always in shipping.”

This sounds like a snippet of dialogue from a Godfather film, with shipping taking the place of Cosa Nostra.

But then Christodoulou is shifting in his chair in the palm-filled patio of the Loews Miami Beach Hotel in South Beach and explaining how he wound up managing a firm called Blink Charging Co.

Last year, he was working at commercial manager Galeon Navigation in New York when he was approached by a headhunter who was attracted by his experience in taking companies public.

The home page on my computer is and always will be TradeWinds... Once you’re in shipping, you’re always in shipping

James Christodoulou

Besides Genmar, Christodoulou was involved with IPOs of two companies that eventually went public — Top Ships and OceanFreight — and two that never quite made it — Prime Marine and Eastwind Maritime. Thus was born the IPO King tag in the pages of TradeWinds.

Although Blink had been around for nine years and was already listed, “it was an early-stage public company, it was transitioning from a ‘mom and pop’ shop to a Nasdaq-listed company in an industry that was going to start moving very quickly, an industry that was coming to real investor visibility”, he says.

Of course, the 59-year-old brings this back to shipping. The scenario reminded him of the early days when he and Georgiopoulos were plotting an IPO flotation in New York when there were only a handful of listed shipowners.

“They were the same kind of dynamics that Peter and I were facing at Genmar in 2001,” Christodoulou reflects. “Although it’s a completely different sector, both were sectors that had been around for years looking at the public markets and were just beginning to gain attention and traction with investors.”

So at a stage when shipping is going through its own environmental transformation with IMO 2020 and carbon emissions reduction, Christodoulou has jumped to another level.

“Having been in shipping and understanding energy, the migration from hydrocarbon to electron was kind of simple for me,” he says.

The transition prompts the question: with what he now knows, does Christodoulou foresee the electron migrating to his old industry?

“Absolutely I think we will see electric ships,” he responds. “I can’t say it will be in my lifetime. If you asked someone in 1945 about nuclear-powered ships, they’d have said you were crazy, but then it happened.

“So I can’t tell you that in 20 years or 15 or even 10 that we’re not going to see electrically powered ships. I can’t tell you exactly what the technology will be, but I can’t rule it out.”

He also posits that electrification will change shipping in ways other than propulsion, if more indirectly.

With more electric cars and buses, “power can be generated more closely to where it’s being consumed — that means a change for tanker trading patterns in crude and products”.

One fuel that has propelled ships and shipping over Christodoulou’s career is capital. It’s his speciality, and the capital markets are where he continues to focus in his new job.

He sees shipping as an industry of “big moves”, with tens of millions of dollars — sometimes hundreds of millions — deployed at any one time on a vessel or fleet acquisition.

“Here you make smaller moves,” he says in relation to the still-growing Blink operation.

The big move with which Christodoulou will always be associated is the General Maritime IPO of June 2001.

He was the lead financial man for Georgiopoulos, a swashbuckling shipping entrepreneur who had privately been building a tanker fleet for years and was looking for the right opening to go public.

Public shipping companies were not the norm. Names such as Overseas Shipholding Group, Teekay Shipping, OMI Corp and Nordic American Tankers were outliers among US listings.

James Christodoulou has a Bachelor of Arts degree from Rutgers University in New Jersey and an MBA from Columbia Business School. He was chief financial officer at General Maritime from 1999 to 2004, overseeing the tanker owner’s listing on the New York Stock Exchange in 2001. He also played a critical role in the $600m acquisition of seven tankers from Metrostar in 2003.

After short stints at Prime Marine and Eastwind Maritime in 2004, ahead of expected IPOs that never eventuated, Christodoulou worked at Dahlman Rose & Co, a New York investment bank specialising in marine transport, energy and oil services. He joined OceanFreight International as chief financial officer, helping it list on Nasdaq in April 2007.

Christodoulou then became CEO and president of Industrial Shipping Enterprises in 2007, before spending six years as president of French tanker owner Angelma. After two years as chief financial officer at Galeon Navigation, he joined Blink Charging Co.

Stelmar Shipping, led by Greek businessman Stelios Haji-Ioannou, managed to go public in March 2001 with an $84m IPO. Then came Genmar.

“When Peter and I went out on the road to investors and said ‘shipping’, they thought we worked for UPS or FedEx,” Christodoulou recalls.

“It’s not that shipping wasn’t welcome. It just wasn’t well known. Then Stelmar, Genmar and Tsakos Energy Navigation [TEN] all came public within months of each other and that was the tip of the spear that brought investor awareness. Then the floodgates opened.”

Genmar took in $144m with its crude tanker offering. TEN followed in March 2002 with a $95m raise. Then shipping took a breather in New York until 2004, when Top Tankers (now Top Ships) and a predecessor to Navios Maritime won listings.

What followed was a record 2005 that saw 11 owners list for a cumulative $2.6bn, with an entire peer group of public dry bulk owners launching.

“I think Peter created an incredible awareness of shipping in the US capital markets that helped pave the way for the later deals,” Christodoulou says.

“Working with Peter to help take Genmar public is still one of my proudest accomplishments and to this day that is the greatest period of my life.”

Yet as TW+ visits Christodoulou, the climate for shipping IPOs is as ice-cold as the Miami Beach surroundings are balmy.

The gap since the last successful mainstream shipping IPO in New York has reached four years, and, probably not coincidentally, it was by Georgiopoulos in June 2015.

No one has to explain this to Christodoulou. Besides reading TradeWinds, he has kept his hand in the game, attending conferences and co-moderating the past two equity analyst panels at Marine Money Week in New York.

So why is shipping so unwelcome?

“I’d say unwelcome is the wrong word,” he replies. “But the way shipping should be run and the way that the capital markets wanted a shipping company to be run are ill suited to each other.”

While shipping is a rough business, the best and brightest have been able to make huge fortunes operating privately, he notes.

“The capital markets by and large want predictable, somewhat consistent growth, and we all know that’s not shipping.

“In order to satisfy Wall Street’s requirements for a public company, the listed owner had to try to create profits and cash flow from sub-optimal acquisitions, to show fleet growth and revenue growth and bottom-line growth.

“They had to go too far out on the risk curve as far as leverage is concerned. The investors forced shipping companies to contort themselves somewhat. Taking on excessive leverage to show growth or profit is not good for a shipowner.”

Public shipowners also have become a home for fast hedge-fund money or “traders” more than investors willing to hold the stocks.

“I really believe there is a very important place for shipping in the capital markets, but it’s got to be patient money that allows a shipping company to maintain a balance sheet to sustain market volatility and not risk bankruptcy,” he says.

“That includes a strategy of selling assets and returning capital, being willing to shrink the fleet when conditions dictate: because it’s the right thing for investors, not because you’re being pressured by the banks.”

No, Christodoulou doesn’t sound like a guy who has checked out of shipping entirely.

In the meantime, he draws on an analogy from his soccer days — he helped a team called New York Pancyprian-Freedoms win the US Open Cup in 1980 while playing sweeper — to describe his duties.

“A sweeper would read the field of play and try to get the attack started in the right direction. That’s kind of similar to what I do now in business: watch and hope I start the attack off on the right side of the field,” he says.

And life is good.

A few months ago, Christodoulou married an Italian-born woman some years his junior.

“She has absolutely no shipping connections except she knew me when I was in shipping, which means she knew me when I was broke, and she kept going out with me,” he says, grinning broadly.

And then there is Miami, where waves just off the patio crash over a salsa soundtrack as the early-evening shadows of palm fronds dance.

“As much as I miss the friends and family and the hustle and bustle of New York, I have to tell you, it’s not a bad place to be.”