An operation to recover the biggest ever cargo of silver sunk at sea led to the discovery of a unique set of letters posted but never delivered in 1940.

Those letters, which are now on show, are the inspiration for a piece of interactive children’s theatre.

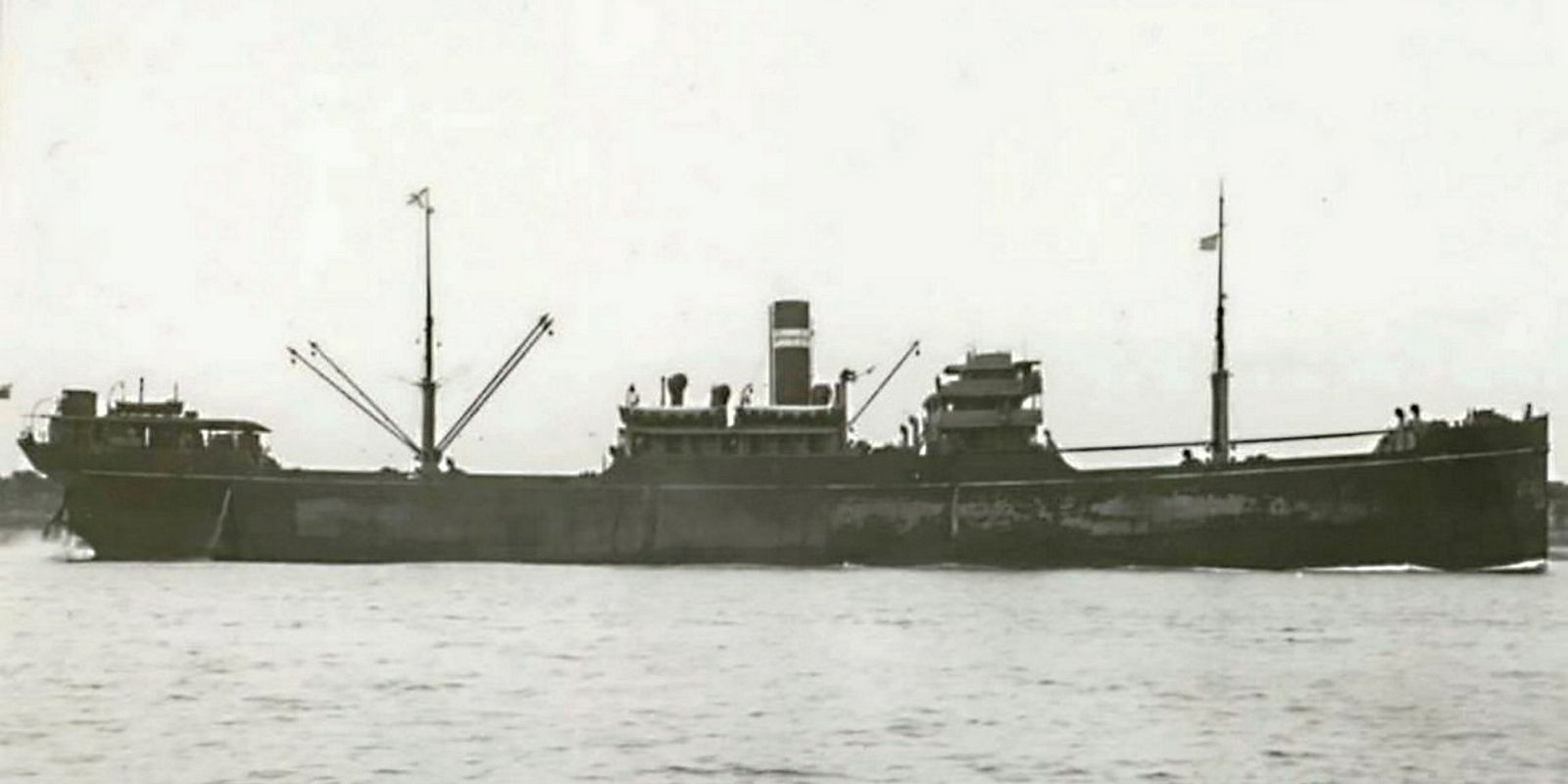

On 16 February 1941 the British India Steam Navigation Co cargoship Gairsoppa, carrying 2,817 silver ingots weighing 109 tons, was sunk by a German U-boat in the Atlantic Ocean 300 miles (480km) southwest of Ireland.

The 5,237-gt Gairsoppa had dropped behind its convoy as it ran short of coal on the final leg of its voyage from India to the UK. The 21-year-old steamship sank in about 20 minutes. Although the mixed Indian and British crew of 84 got off the vessel, only one of them, second officer Richard Ayres, survived the 13 days it took for his lifeboat to wash up at a small Cornish cove off southwest England.

It took a further 70 years to discover the wreck, which lay in waters more than half a mile deeper than those in which the Titanic rests. Plans were laid for a deepsea salvage operation by US company Odyssey Marine Exploration.

That expedition recovered nearly half the $200m silver cargo and found a whole lot of other less valuable but equally interesting items in the wrecked hull.

Many of the crew’s belongings and much of the other cargo of pig iron, tea and fertiliser had been preserved in the icy depths 2.9 miles (4.7km) down. Astonishingly, 770 personal letters had also been preserved in the sediment.

Those letters are at the heart of the Voices from the Deep exhibition, running until January 2019, at London’s newest museum. And this exhibition at the Postal Museum is the inspiration for a new programme aimed at primary schools developed in collaboration with Big Wheel Theatre Company to bring it all to life for today’s children.

Postal Museum schools learning manager Sally Sculthorpe says the collaboration with Big Wheel allows the museum to create immersive, engaging theatrical workshops linking with stories and objects from the exhibitions.

“Lots of museums show original objects to children, but what we do uniquely is that with Big Wheel’s theatrical background we bring these stories to life in a way that we could not do on our own,” she says.

Big Wheel co-founder Roland Allen adds: “The thing we do differently is to combine the education and the entertainment at the same time. A lot of theatrical companies will do a play and then they will talk about the lessons we learn from the play. With us, it works as part of a coherent whole.

“Schools really want the educational side of it because they have got to tick their boxes, but our task is to make something that is not like a lesson that the teacher can do, but something that is really exciting and fun — a moment the kids will always remember.”

The schools programme performances bring to life stories from social communications history. Actor-led workshops provide opportunities for children to “meet” Sir Rowland Hill, who reformed the postal system in the 1840s, or a British suffragette who posted herself to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith as part of the protests that led to women getting the vote.

The children can get hands-on with original objects held by the museum. “One of the big ‘wow’ moments for them is holding something that is 100 years old, like a Penny Black stamp,” says Big Wheel actor Emily Sly.

The museum provides packs of digital learning resources to back up the teaching. “What gets schools out of the classroom and into places like the Postal Museum is cross-curricular learning — bringing together STEM subjects like science, technology and maths with history and other disciplines,” Sculthorpe says.

With the Gairsoppa, the story and some of the material were sensitive. The Postal Museum and Big Wheel decided they did not want to place the learning in the context of the sinking, as the crew did not survive, but focused instead on the ship’s salvage.

“We quickly homed in that the best thing was for the children to be marine archaeologists in an explorative role,” Sculthorpe says. So the workshop will involve an audio-visual set-up that replicates the control room on Odyssey Marine’s salvage vessel for the remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) that had to recover the bullion and many delicate objects.

“The operation had to come up with ingenious ways to bring the finds up,” Allen says. “The silver was almost the easiest to handle, as it could be shovelled into crates. But dealing with fragile fabrics, shoes and glass needed penny arcade-type grabbers and suction hoses and a limpet that fastened to objects very gently. Somehow we are going to create a human ROV that has all these things.”

Among the many bottles, Indian sandals, Western shoes and the ship’s lantern that are now on display at the museum were the most fragile objects of all, 12 bundles of letters written as Christmas 1940 approached that had somehow stayed dry until recovered. Soaked and slimy from the recovery, the largest collection of lost mail from any shipwreck went through an intensive conservation process.

From that restoration emerged a vivid snapshot of the voices of British soldiers, Indian royals, government officials, businessmen, services wives, children and missionaries writing to loved ones in Britain and the US at a time of high peril in World War II.

Many express their fears for those at home undergoing the bombing of the Blitz after Europe had fallen to Hitler. A colonel notes the importance of the US coming into the war. Others talk of their hatred of Hitler and pleasure that the Greeks had repelled Mussolini’s first attempt at invasion.

Expressions of love and dreams of the future peace also abound, with details of daily lives in India ranging from cinema visits and games of golf to leopard attacks and snake bites.

The Gairsoppa’s cargo also reveals the importance of India to the war effort. By the start of 1941 the UK’s Royal Mint was down to five weeks’ silver reserves and the lost bars were equivalent to three months of supplies. Likewise, the tea on the ship was a serious loss and could have kept London’s population of 8.6 million in “cuppas” for nearly a month.

Iron and steel production from India remained crucial throughout the war, as the UK possessed only six blast furnaces capable of producing 3,000 tons a week in the 1930s and four mechanised grab transporters for unloading ore, compared with 20 in Rotterdam alone. Even the high number of empty bottles found on the wreck suggests many were being transported back for recycling because glass was in short supply.

Attack by U-boat was the nightmare of all seafarers during the war. By the time peace arrived, 22,940 British merchant seamen and more than 6,000 Indians had died, and British India Steam Navigation had lost nearly half its fleet of 105 vessels. It is estimated that ships like the Gairsoppa will have rusted away within another century. It is time for their fate to be heard.