Finally, after almost a decade and 16 winners of the Onassis prizes for shipping, trade and finance, there is a woman laureate.

In this era of heightened awareness of the lack of diversity throughout the professional world, Professor Mary Brooks is proud of her achievement and determined to play a part in changing the landscape.

“I’m a firm believer in diversity,” Brooks tells TW+ the morning after receiving her honour at a gala dinner in London’s historic Guildhall.

“You can use this to harness the power of bringing more and more people into the tent for discussion. Ultimately that’s a female way of doing things,” she says between sips of water and nibbles of a sandwich snatched between lectures and receptions at the Cass Business School.

“I’ve always said, put women on boards, put people who reflect your customer base on the board of your corporation, and you will get better decision-making. Women don’t always think the way men think and industry doesn’t always tolerate an alternative point of view. Lots of views on the table, lots of collaboration, will always give you a better outcome.”

Brooks received her Onassis award for more than four decades of work on port governance and liner shipping competition policy.

“Diversity of viewpoints always gives you a better perspective. The perspective on port governance and port reform has revolutionised over the last 15 years because people have been talking to each other,” she says.

As Professor Emerita at the Rowe School of Business at Canada’s Dalhousie University, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, she has played a significant part in the development of academic study of questions facing liner shipping and ports. But her life nearly took a very different direction.

“I was an occupational therapist for six years. It was soul-destroying. It wasn’t for me. I reached a stage when I just couldn’t do it,” she reflects.

She quit, and as she had a first degree, decided to enrol for an MBA on a course where she came under the tutelage of British-Canadian businessman, lawyer and academic Sir Graham Day in his business strategy class. He would become her first mentor after being impressed by her solution to an end-of year exam question.

“It was just one of these problems that had a long-term issue, but everybody was used to solving problems with short-term solutions. So I spent five hours and mapped a longer-term answer,” Brooks recalls. “Graham said I had absolutely blown it out of the water!”

She went on to work for Day. One of the first projects was recording the code of the contents of every container coming into Canada at the ports of St John, Halifax and Montreal.

Remarkable as it sounds today, she says no one really knew the detail of what was being imported, as the figures could not be easily compiled in the era before powerful computing technology. “I’ll always remember that it came as a shock that one of the biggest imports in Montreal was wine for thirsty Quebecois!”

From those early shipping projects, Day recommended her to Professor Richard Goss at the University of Wales in Cardiff. Day would go on to be a high-profile figure in the UK, including as chairman and chief executive of British Shipbuilders from 1983 to 1986.

Goss, who won an Onassis prize himself in 2012, became Brooks’ PhD supervisor and second mentor.

In the years that followed, Brooks was forced to develop the skill of jumping from one stream of research to another as they came in and out of fashion.

“I’m a firm believer that there are cyclical fields of research, so I had to become an opportunist. As long as it was in one of three or so streams, including shipping, trade or port management strategy, there was some coherence.”

She hopes another phase in the research cycle is approaching: “What really excites me is that I really want to see that competition policy element go full circle again and come back to the fore. I want to know what’s important to research, and if I can help, I will be thrilled.”

Having graduated her last PhD student two years ago, she now focuses on mentoring, advice and partnerships.

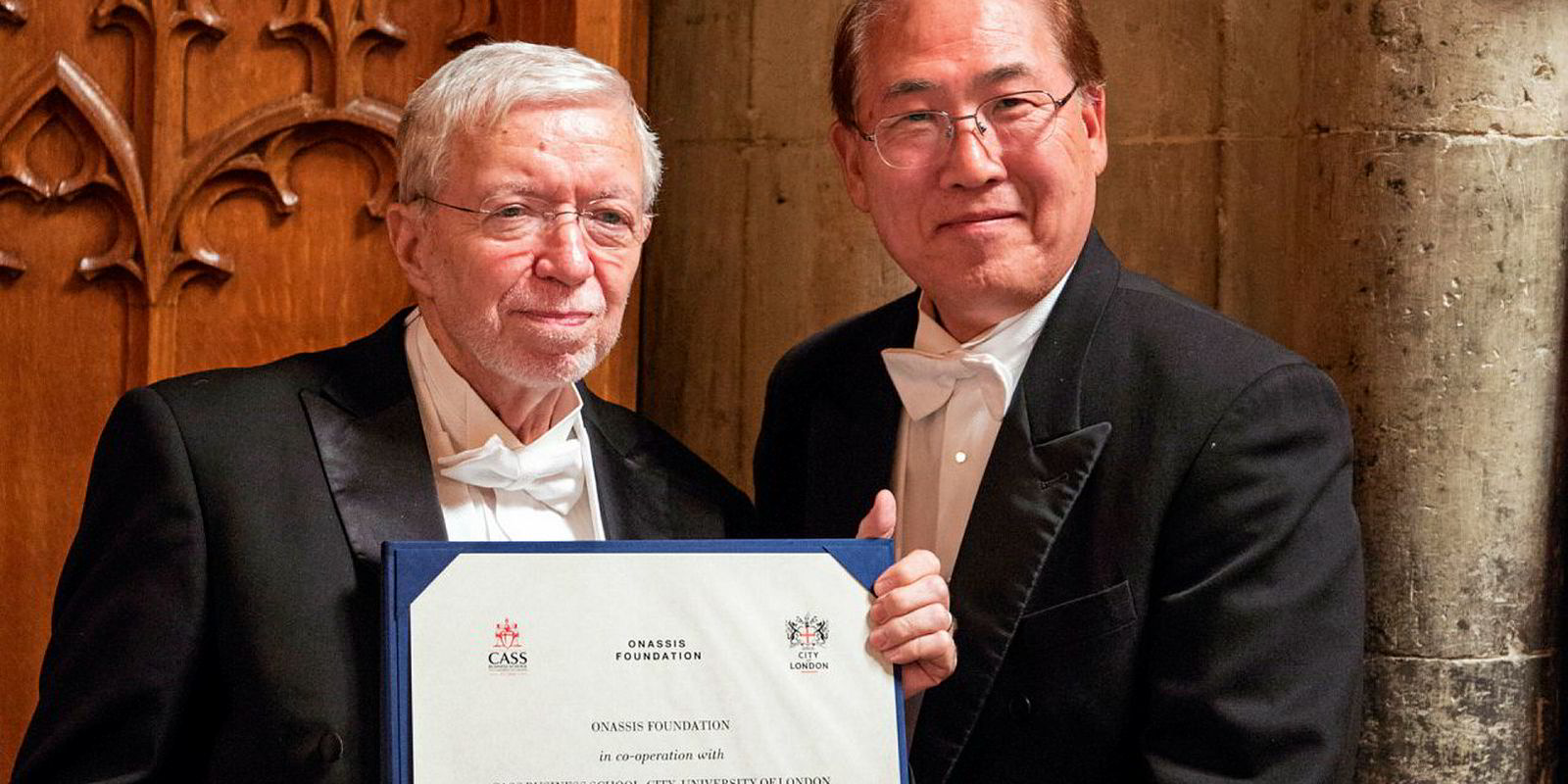

Brooks shared this year’s $200,000 Onassis prize in shipping with Professor Wayne Talley of the Strome College of Business at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

Although they have different areas of expertise, both intend to use their prize to help fund students.

Talley, 76, plans to fund a PhD post. “Can you believe it, but in the US there is no PhD offered in any university in maritime business. It’s incredible. Maritime business is not an academic area in the US. Someone has to start it!” he says with passion.

Establishment of the post will take time, however, because of the need to gain approval from the Virginia public education authorities.

Brooks intends to help support scholarships through her prize. She blames the Brian Mulroney government in the mid-1980s for cutting all funding for Canadian university research into transport “in one stroke of the pen in one budget”.

During her acceptance speech she said she would be “proud to support Canadians and new immigrants to Canada”.

It is a theme she is keen to expand on when we meet the next day.

“The key word was new immigrants,” she says. “Because I am a firm believer that the knowledge economy the other prize-winners were talking about — trade, innovation, insight — means that our new immigrants will be the engine of the Canadian economy.”

And she shows anger at what is going on south of the border. “I’m sorry Mr Trump is targeting this. I think he is making one of the biggest mistakes for America in his approach to immigrants. I’m a firm believer in diversity.

“Diversity is helped by immigration and I like the fact we have lots of immigrants. It doesn’t bother me at all that Canadian tax dollars are being spent on helping people who don’t speak English or French.

“We figure out how to help them and support them for a year. We just hope that the people we have chosen are flexible enough to become Canadians and want to be part of our community. If that’s the case, then bring ’em in!”

Such straight talk is one of her strengths, she believes. Academic research on transport has “always been a tough sell”, she concedes.

“But integrity and straight talking has been one of the strengths that I’ve had, and one of the reasons I’ve been able to get to this point. If you have integrity at the core, if you always do what you say you will do and you don’t over-promise and you tell it like it is, then you have integrity and honesty. And then you have trust. If you haven’t got integrity, you’ve got nothing.”

With that, she finishes her sandwich, and with a generous smile she’s off to the next celebratory reception.

Awards that were born out of tragedy

The Onassis International Prizes in shipping, trade and finance were launched in 2008 as part of an expanding suite of awards backed by the Alexander S Onassis Public Benefit Foundation.

The foundation was set up with 45% of Aristotle Onassis’ fortune after he died in March 1975 at the age of 69, two years after the heartbreak of the death of his son Alexander in a plane crash.

His will set terms for creation of a foundation based on the Nobel Foundation in Sweden “for the establishment, maintenance, and general functioning of and assistance towards medical, educational, literary, religious and in general scientific, exploratory, journalistic, artistic institutions with competitions held internationally or nationally accompanied by monetary prizes”.

The prizes are awarded every three years. Since they were established in 1978, their development has gone through three stages, starting with awards for culture and social issues, followed by the arts, before moving on to issues such as the economy and the environment.

Since the first Onassis prize in finance was awarded in 2009 to Chicago’s Professor Eugene Fama — who went on to win a Nobel prize in economics — they have been expanded to include trade and shipping research.

Run in collaboration with the Cass Business School, part of City, University of London, they have earned a growing reputation. In 2015, Clarksons’ Martin Stopford was one of the joint winners of the shipping prize.

“The aim is to establish these prizes as the Nobel prizes of the City of London, in areas of relevance to it and which the Nobel prizes do not cover,” says Professor Sir Paul Curran, president of the university.

Anthony Papadimitriou, president of the Onassis Foundation and chair of the judging panel, describes the awards as a fitting tribute to their benefactor.

“Aristotle Onassis’ name is synonymous with the spheres of endeavour in which our laureates are engaged, and shipping, trade and finance are the three core areas of business activity in contemporary economies,” Papadimitriou says.

With a proud smile he adds that the fleet now managed by Onassis’ Olympic Maritime is “larger, newer and more valuable” than the one bequeathed to the foundation when it was set up in late 1975.