The man who is set to be China’s first private LNG shipowner is already its biggest private tanker owner. Ye Cheng’s Landbridge Holdings ports and terminals group will soon take delivery of its sixth VLCC.

Ye looks certain to make his next shipowning move in LNG carriers. In 2014, TradeWinds reported that he was ordering ultramaxes at Chengxi Shipyard, but was talked out of it by his guardian angels at China Minsheng Bank, according to domestic press reports.

A Landbridge official says only that the company has a good relationship with Minsheng but has no current plans in dry bulk.

When an LNG receiving terminal in his home base of Rizhao is completed and paired with Landbridge Group’s Australian gas producer Westside Corp, a self-owned LNG carrier fleet will complete a Landbridge-owned chain of gas supply and transport from Queensland in eastern Australia to the Chinese province of Shandong.

Deals like that, crucial to the credibility of China’s global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), call for a special kind of deal-maker who brings a specific combination of advantages to the execution: the flexibility of privately owned entrepreneurship and the political weight of regulators and state financiers.

That combination has drawn growing scrutiny from some of the countries the BRI is meant to reach out to. In Australia, the deals have become a constant focus of controversy over China’s influence.

Ye’s successes in Australia with natural gas and ports have made him Exhibit A in the case for tightening the national Foreign Investment Review Board process.

Shipowning is just one piece of Landbridge’s closely integrated holdings, and certainly not the piece that gets the closest personal attention from its politically connected owner.

Starting from Rizhao in smoggy coastal Shandong, Ye has turned what was founded in 1992 as the Rizhao City Port Harbour Petroleum Co into a trans-Pacific logistics and trading empire.

He first drew big international headlines when he connected his home base to Australia in 2015 with a controversial deal to lease the Port of Darwin for 99 years. Next year, Margarita Island port on the Panama Canal joins Landbridge’s growing system of ports, terminals and refineries, as well as related trading and shipowning interests.

Throughout the building of Landbridge, Ye has enjoyed the support of regional and municipal Communist Party leaders in Rizhao, where his massive base can boast of being China’s biggest privately owned port operations on the dry and the wet sides.

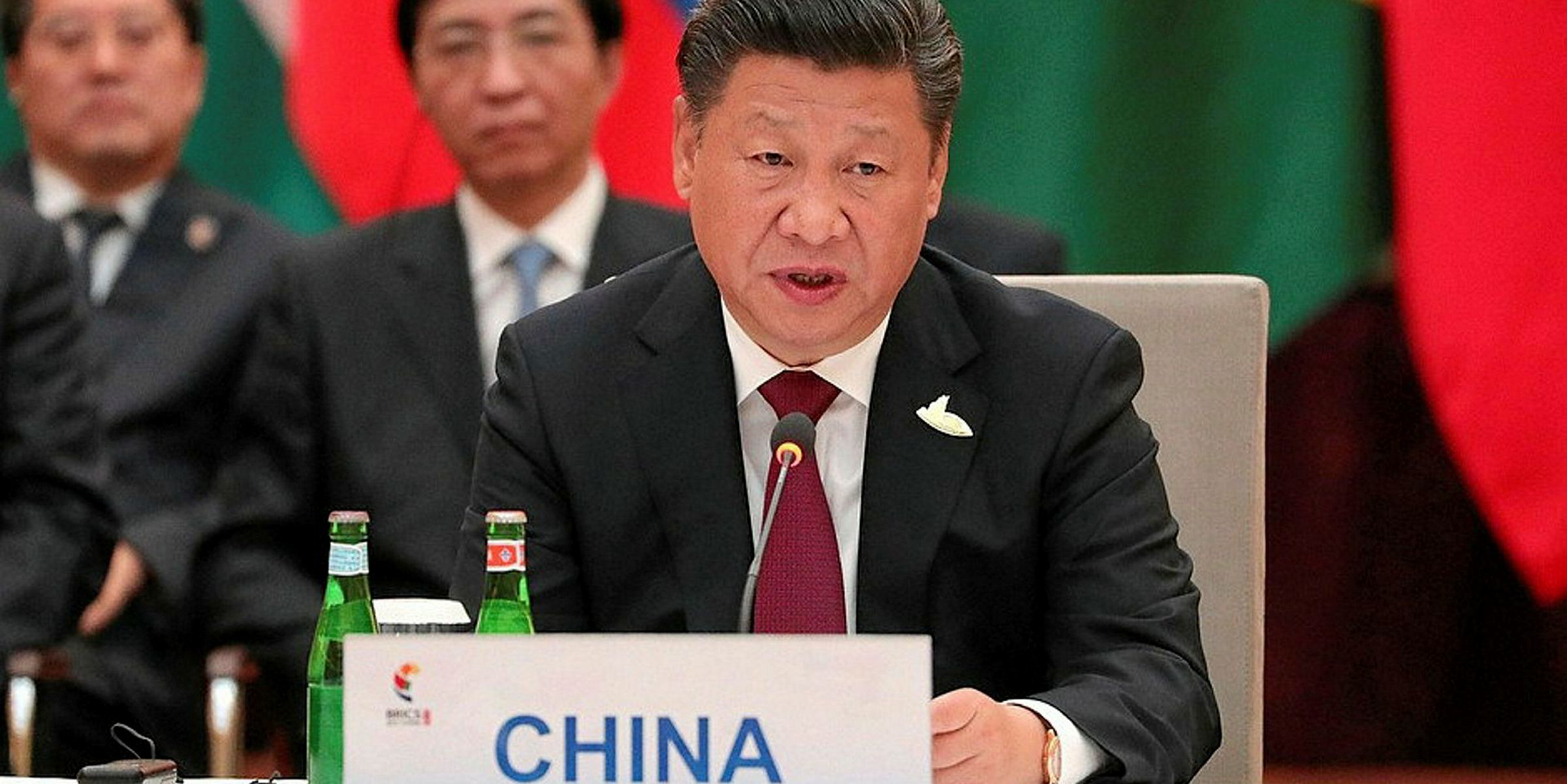

And since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, it has been evident that Ye’s political connections reach to the very top. Xi appeared with Ye in Australia to give his blessing to the Darwin project at a 2015 signing, and the two leaders’ interests are clearly in harmony.

Xi’s trademark BRI, a package of slogans and proposals that he cobbled together from existing initiatives and adopted soon after becoming president, encourages Chinese businesses to undertake just the kinds of jobs Ye is interested in — the kinds that bridge China to its trading partners with logistics and commodities infrastructure.

Private businessmen such as Ye have been well suited to spearheading overseas deals for Beijing, where big state-owned enterprises (SOEs) including China Cosco Shipping and China Merchants Group might meet more political opposition.

For his successes in doing so, he has served as a member of the non-lawmaking but high-profile Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee, although he apparently dropped out after the 2018 session.

High-level connections inspire the suspicion that a private Chinese deal-maker like Ye is under orders.

“You have to work on the basis that Landbridge is really acting as an arm of the Chinese government when it makes its big foreign investment decisions overseas,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute executive director Peter Jennings told Australia’s New Daily newspaper last year.

Ye’s control of the Port of Darwin, next door to a US military base, has been one of the main lightning rods for criticism of Chinese influence ever since the signing, more so after the revelation in 2017 that former Australian trade minister Andrew Robb had gone from his government position to an A$880,000 ($602,000)-per-year consultancy with Landbridge.

The truth is more complicated and arguably less sinister. Xi and the BRI need people like Ye and latch onto them because they can walk China right into the places that the state’s directly owned businesses can only fumble towards.

Individuals who build large businesses are probably a recognisable type across all national boundaries. But the career trajectory of an entrepreneurial spirit follows a distinctive pattern in China, because in many cases the starting point is the same — a neglected but deserving local SOE.

Languishing state enterprises are the forgotten roots of an overlooked privatisation with Chinese characteristics that gave birth to companies such as Landbridge.

No fire sale of crown-jewel assets on a Russian scale happened in China. But it would be a mistake to say there was no privatisation. It just happened closer to the ground.

The very biggest assets remained under government control as today’s “central SOEs” or the provincial equivalents, but just about any city or region can point to some shiny corporate successes that were fostered out of gritty industrial assets.

Many a medium-sized factory or shipyard, provincial transport monopoly (or, in the case of Rizhao and Ye Cheng, small fuel business) was begging to be developed into something more efficient and profitable.

In China, that demanded not only a visionary but someone who had the blessing of the party.

With that starting point — the development of a local success story under the approving eye of local political authorities, with all the types of cooperation that that entails — businessmen like Ye have been crucial to the success of Xi’s BRI. The point is not that they are acting under orders, more that they have an agenda of their own: profit-driven reasons for projects that line up with the BRI’s goal of building bridges between China and its suppliers and markets.

Such a class of business-builders with strong local support gives China a kind of energy it is not getting out of its directly owned corporate giants.

Despite the big state actors’ frequent resounding endorsements of BRI propaganda, the SOEs have actually been remarkably reluctant to implement BRI projects, according to a study by Boston University’s Min Ye (The Domestic Politics of China’s Belt and Road Initiative).

“Going global, SOEs are required to ensure the return and safety of their assets, help achieve political agendas, and not create a social and diplomatic backlash. Chinese SOEs, in fact, have been ‘risk averse’ in investing abroad,” she wrote.

International and Chinese observers of BRI implementation have missed the point that it is commercially focused actors with strong local government backing — as in the case of Landbridge, Ye Cheng and Rizhao — that have tended to be the ones to make the most of the BRI.

“[It] is the local dynamic that largely explains the popularity of the BRI inside China,” Min Ye wrote. “The ability to leverage the BRI and interpret it flexibly has helped local governments carry out their development projects and revive the local economy in the last few years.”

Landbridge dives into shipping at the deep end

Landbridge Group did not take the gradual route into shipowning.

From its shoreside core businesses of dry and tanker terminals and petroleum refining, it started right off as a VLCC owner in 2013, setting up Hong Kong-based Landbridge Holdings to order a series of newbuildings at Dalian Shipbuilding Industry, all subsequently lease-financed by foreign private equity and China’s CSIC Leasing

Having become China’s largest private tanker owner with no previous shipmanagement or commercial operating experience, the new entity began by outsourcing many aspects of its business. Hong Kong neighbour Wah Kwong Maritime Transport took on Landbridge’s newbuilding supervision, technical management and commercial operations, as well as lending its expertise in areas such as ship finance.

Chao family-controlled Wah Kwong, then in the midst of a generational transition, was publicly emphasising the importance of its “asset light” business lines such as supervision and technical management, and its ability to connect with mainland owners, including financial leasing institutions and Landbridge.

Soon, however, several Wah Kwong executives jumped ship, including chief financial officer Vincent Lai King Yip, who became chief executive at Landbridge Holdings. The new company’s commercial director, Ray Lei Yutian, and the managing director of Landbridge Ship Management, Sanjeev Verma, also came over from Wah Kwong. And as of earlier this year, none of Landbridge’s vessels are in the hands of third parties.

So far, Landbridge’s conservative chartering strategy has been similar to that of the traditional Hong Kong family companies whose experience it borrowed. Of its six VLCCs, two are in the Navig8 VLCC pool and the others are on long-term time charters to blue-chip clients such as BP and Trafigura.

Exposure to peaking tanker charter rates will be at most through Landbridge’s pool ships, not through long-term spot operating on its own. On a visit by TradeWinds to Landbridge Holdings in Hong Kong in October, Lai explained that the company is not focused on maximising charter returns in the short term but on providing tonnage for customers, with which it does oil trading business as well as chartering business.

Landbridge is expected to continue its expansion in the VLCC space, but also to become an LNG owner. In the summer, it signed on to collaborate in developing an LNG regasification terminal in Rizhao to serve client Beijing Energy Group at the downstream end, with Landbridge Group’s Australian subsidiary Westside Corp supplying the gas.

As with its crude carrier business, Landbridge’s LNG plans start it off right at the top, making it the main privately controlled Chinese shipowner in its market segment.