Time charters have been built to endure a lot. After all, their essential structure has remained unchanged for more than a century.

But they were not built for the International Maritime Organization’s Carbon Intensity Indicator.

The CII is seen as a potential spark that could ignite litigation between shipowners and their time charter counterparties, although it will depend on how much weight the regulation’s carbon intensity ratings ultimately have in shipping markets.

The litigation risk is partly rooted in the fact that a ship will receive CII ratings that are affected by the vessel’s technical characteristics and by how it operates.

“Technical capacity of the ship, that’s owners’ ballpark,” says Rachel Hoyland, a lawyer who handles shipping litigation at Hill Dickinson.

“But when you come on to how has the ship been operated and has it been operated in an efficient way, a lot of that is usually within the charterers’ realm.”

How fast a ship goes, what route it takes and how much cargo it loads are all decisions made by charterers. If carbon intensity is affected by bad weather or congested ports on that journey, the CII rating could take a further hit.

Hoyland says the fact that CII ratings are assessed retroactively also creates litigation risk, depending on whether they lead to different ship values in the future.

If choices by a charterer lead an A-rated ship to become a C or fall into the non-compliant D or E category, it could cause a dispute.

“You then have a vessel which is potentially less valuable in the market that you want to trade in. So that’s where your loss arises,” Hoyland says.

For lawyer Alessio Sbraga, a partner at HFW, the nature of the CII rules is just one problem. Another is rooted in the nature of time charter contracts. “The CII regime cuts through the heart of the normal time charterparty contract,” he tells TW+.

Typically, a shipowner has to follow a charterer’s orders, which could have a direct impact on the carbon intensity.

“And taking preventative steps such as slow steaming, deviating [or] reducing cargo intake will all improve the CII but have a direct impact on the contract and could place them in prima facie breach of their contractual provisions,” Sbraga says.

That could lead to a claim for damages or, in the worst-case scenario, termination of a charter contract.

A shipowner facing such a claim may have defences, but they are likely to be complicated and rest on the specific facts and circumstances of each situation, and the wording of contracts.

And then there’s the regulatory uncertainty of the CII regime.

“It appears that the regulations lack regulatory teeth,” Sbraga says. “There are no formal penalties or sanctions that exist at the moment. However, that’s probably not the end of the story, because of course the reality is these regulations will probably have more commercial teeth than anything else.”

But whether CII ends up having contractual teeth is a matter of speculation at this point. Lawyers say it would depend on whether shipping or finance markets assign a different value to vessels that have different CII ratings, resulting in a multi-tiered market.

How can shipowners and charterers prevent CII from turning their commercial dealings into legal kerfuffles?

Legal experts say what is needed is contractual language that lays out a new relationship between charterer and shipowner, one in which they have to work together in ways they never have before to ensure a vessel meets a minimum C rating or higher if it is the owner’s intention to achieve it.

“What it requires is a robust contractual framework that takes into consideration what needs to happen going forward, which is a modified contractual relationship with two key ingredients: the first being collaboration, the second being transparency,” Sbraga says.

Identifying that contract framework has not proved easy.

A case in point is the effort by Bimco, an industry group that includes shipowners and charterers among its members, to draft a time charter clause for CII. It was expected to be published in May this year but is now predicted for November, less than two months before the regulation comes into force.

Stinne Taiger Ivo, director of contracts and support at Bimco, says the group has been working to strike the right balance and to craft language that is widely accepted in the industry.

Key to the CII’s contract challenge is that how a charterer trades a vessel plays a big role in its carbon intensity rating, she tells TW+.

“So that makes it difficult, in a way, for charterers to accept that they are also part of the whole game to get this to work in practice, and to be there as an active party ensuring that the owners would actually comply.”

The contract clause is ultimately expected to involve language that requires owners and charterers to cooperate — and that requires an exchange of data. Charterers may have to accept limitations on their freedom to trade a vessel.

Lawyers who have been proposing clauses of their own for shipping contracts that continue into next year tell TW+ that some charterers have been pushing back on giving up the power to trade the vessels as they see fit.

Although some charterers have expressed a desire to reduce carbon emissions in their time-chartered fleet, for the rest, the hesitation to sign away trading freedoms they have long enjoyed is not difficult to understand.

Facing a toothless global regulation whose commercial weight remains uncertain, why would they?

The people getting the most insight right now into that question of charterer resistance are also among the people who are most likely to face the disputes that emerge after the new regulations hit the fan — the lawyers drafting the long-delayed Bimco CII clause.

Charterers that go along with new decarbonisation-friendly charter terms, they say, will have had a better basis for negotiating CII issues.

Charterers that have resisted will be the ones taking their counterparties to arbitration over failure to obey lawful orders — and their counterparties will be passing their liability up the chain to the owner.

Formally speaking, the responsible party is the holder of the document of compliance, but it is the shipowner that ultimately faces the financial risk in having a ship busted down to an unfavourable rating of D or E, and that will have to decide whether to comply or risk an arbitration.

“It’s going to come down to circumstances where owners have refused an order or voyage and the charterers say: ‘You’re refusing to obey a lawful order’,” says Helen Barden, the North P&I Club representative on the Bimco committee that has been drafting new charter clauses for CII, the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Design Index and the European Union Emissions Trading System allowances.

The committee is headed by Peter Eckhardt of Hamburg’s Martini Chartering.

Like other P&I club lawyers, Barden has also been involved in reviewing the proposed charterparty language that owners and charterers have been negotiating between themselves in the absence of a CII clause.

But she points out that club lawyers are not normally aware of the final form such private clauses may take when adopted.

Another scenario is one in which charterers contend that a vessel has not been properly maintained, and that is why a CII target has not been met. Bimco clause or not, owners will still face the possibility of such claims.

“Owners are not going to be able to say then: ‘This is all on you, charterers’,” Barden says.

The delays that a new Bimco CII clause faces, plus the resistance of charterers, mean owners must plan for disputes.

“There is no guarantee that a charterer will accept the new Bimco clauses or other decarbonisation-related language,” says a representative of another major club, who declines to be identified, “and P&I clubs may be able to some extent to support an owner who can’t get the right terms.”

But at least two groups of charterers can probably be counted on to be more positively disposed to a new collaborative approach.

First are the major charterers sitting on the Bimco committee that drafts decarbonisation-related clauses, which include BP Shipping and Rio Tinto. They are high-profile companies whose huge chartering operations face pressure from financial investors and bankers to cut their own Scope 3 supply chain emissions.

Second are tonnage-light owner-operators, not least in dry bulk, that understand the CII burden of owners at first hand when trading their own tonnage and might be expected to be easier to persuade when they sit on the other side of the chartering table.

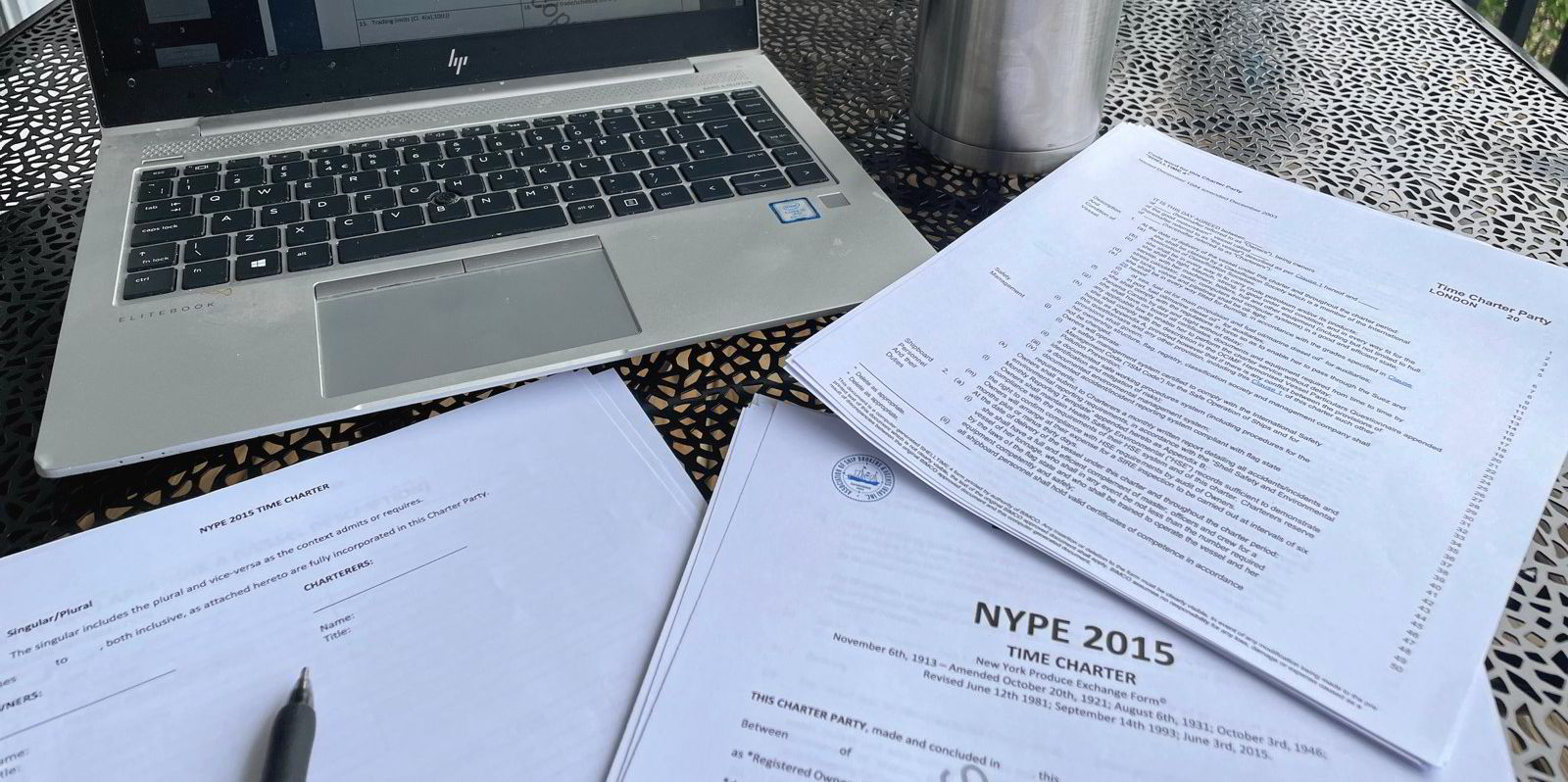

Time charter contracts, or time charterparties, are agreements allowing a charterer to employ a vessel over a period of time at a rate metered in days.

Among the oldest time charterparties still in regular use is the New York Produce Exchange Form (NYPE), which was started in 1913. It was updated several times, most recently in 2015, but some charter deals are still done on versions of the form that are more than a half-century old. The form, used in the dry bulk sector, had competition from an even older form known as Baltime that was created in 1909 and seen as more shipowner-friendly.

NYPE Form managed to outlive the produce exchange it was named after, which was liquidated in 1983.

Those drafting new charter clauses for Bimco tend to see the issue as surmountable — maybe because the charterers they hear most from are those that have already come to the table.

“There has to be an element of dialogue between shipowner and charterer under the CII and there needs to be a contractual framework for that dialogue,” says Barden.

Charterers that have come to the Bimco table are not the problem, according to West of England P&I Club head of loss prevention Simon Hodgkinson.

“Some charterers have ESG [environmental, social and governance compliance] front and centre and may be easier to negotiate CII terms with,” he tells TW+. “The ones I get the most responses from are in general the ones I’m least concerned about.”

But the chartering universe is fragmented and few owners with heavy spot exposure will be able to afford the luxury of sticking to a top tier of ESG-sensitive majors. As Hodgkinson puts it: “Your need to survive as a business requires you to charter to all kinds of people.”

Shipping can be a litigious industry, increasingly so in proportion to its volatility. For some lawyers, the combination of enormous regulatory change and a rising chartering market raises the spectre of a wave of disputes like the one before and during the crash of 2008.

That is not necessarily an unattractive prospect for lawyers in private practice, but the clubs see the matter more from the perspective of their members.

One nightmare claims scenario from the point of view of a mutual insurer is the not-unlikely prospect of an event bringing severe multi-port congestion and owners declining voyages on CII grounds.

Most talk about the operational conflict of interest that CII requirements will cause has centred on voyage speed, because this is where owners can most directly affect their rating. But routing, load factor and the choice of destination are also considerations.

Port congestion is a CII ratings killer because it can vastly increase idling time in proportion to voyage time.

Owners may be motivated to choose the most fuel-efficient route rather than the quickest, to reduce the volume of cargo on some shipments, to prefer long voyages over short ones so that idling time in port is less in proportion to sailing time, and to avoid congested ports for the same reason.

Thus, a Covid-like event, already a headache for insurers because of the huge demurrage claims it would generate, could get even worse under a CII regime when the more litigious figures in the industry smell blood in the water. Especially once CII enforcement has some teeth to show.

“It’s all theoretical at the moment. It might not happen at all,” says Hodgkinson. “But there are always going to be people who try to exploit any event. And part of the problem whenever you have a change of legislation is that some will take advantage of it.”

Barden says: “There are always more litigious owners and charterers, but there are also many that have ongoing relationships they want to preserve.”

She believes that in the end, shipowners may just want to get on with working their ships instead of fussing over regulations: “Owners don’t want to interfere with the charterer’s control. They don’t want to say: ‘No, you can’t carry that much cargo; no, you can’t go to this or that port’.”

But the CII regime will put that instinct to collaborate to the test.

“It demands a change in the way owners and charterers have to work together,” Barden says.

The Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index applies technical standards to cut carbon dioxide emissions by ships from 1 January 2023 based on the Energy Efficiency Design Index adopted by the IMO for newbuildings in 2020.

The Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) will regulate existing ships above 5,000 gt from an operational perspective. It is worked out by taking a ship’s annual emissions from fuel used and dividing that by its capacity (deadweight or gross tonnage), multiplied by annual distance travelled in nautical miles.

The CII will be implemented via a new Part III of the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) containing targets and an implementation plan that details measures to be applied.

From 2024, CII ratings will be assigned for the previous year ranging from the highest A to lowest C pass grades, while D and E results may be considered non-compliant.

Operators of ships rated D for three consecutive years or E for a single year will have to develop an approved plan of corrective actions to bring a vessel into compliance by the end of the next year.

The CII is based on 5% reduction in carbon intensity in 2023 relative to a 2019 base level. Its requirements will get stricter by 2% per year until 2026. The IMO has yet to decide on further levels.