In January 1942, the German submarine U-123 opened fire on a tanker off the coast of Long Island, New York.

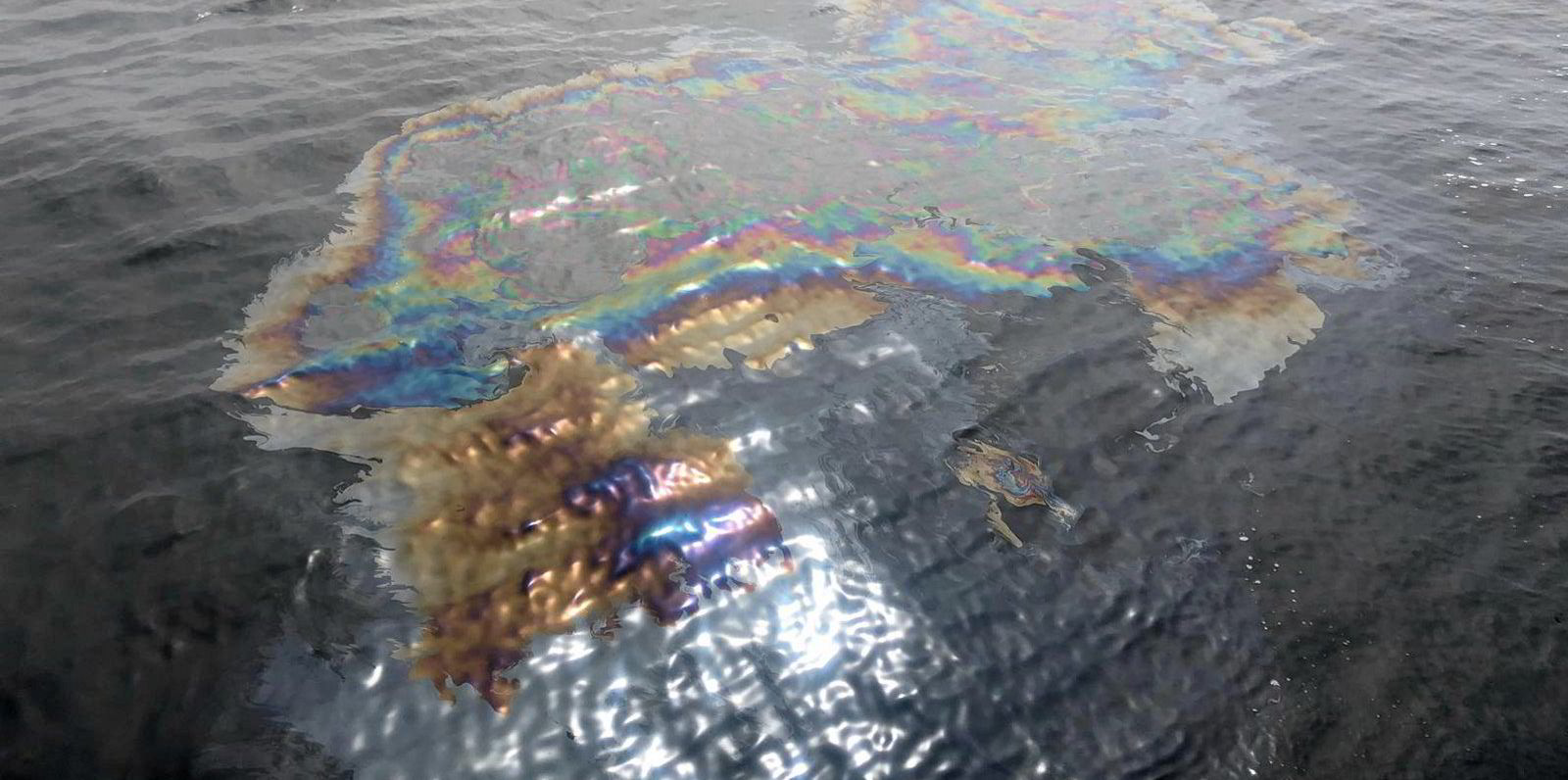

Two torpedoes ripped into the 6,768-gt British supply ship Coimbra (built 1937), but its cargo of lubricating oil remained in its tanks for more than seven decades at the bottom of the Atlantic.

After oil began leaking from the wreck, the US Coast Guard and New York state authorities mounted an operation to remove the oil in 2019.

But thousands more wrecks litter the world’s oceans that are believed to have as much oil as 500 Exxon Valdez oil spills, and as steel from the marine casualties of two world wars degrades, many are silently ticking time bombs that, when they go off, could result in catastrophic spills.

Benjamin Ferrari, a senior advisor to the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, told TradeWinds’ Green Seas podcast there are an estimated 8,500 shipwrecks that could contain 20m tonnes of oil as cargo or in bunker tanks.

“That’s huge, and this is a globally distributed challenge. So it’s not a question of tackling a small number of hotspots,” he said.

“A significant number of coastal states have these potentially polluting wrecks in their waters. What we also know is that closer examination of archives and records shows that’s probably an underestimation of the challenge we face.”

And time is of the essence.

8,500 The estimated number of shipwrecks in the global ocean that are believed to contain oil that represents a spill threat

2.5m to 20m tonnes The estimated amount of oil remaining on sunken vessels

40,000 tonnes The approximate amount of oil spilled from the 214,900-dwt tanker Exxon Valdez (built 1986) in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in 1989

$2,300 to $17,000 Estimated clean-up costs per tonne for oil spills

Many of the shipwrecks that pose a threat are from World War II or even earlier, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that pollution from sunken vessels will reach its highest level in this decade.

The Lloyd’s Register Foundation, the UK charity best known for the classification society that it owns, has been working to build a coalition of partners, including IUCN, to address the problem.

A key partner is The Ocean Foundation, a nonprofit group that is working with the foundation’s Heritage & Education Centre on the Threats to Our Ocean Heritage ocean literacy initiative, which aims to produce a three-book series and convene a network of experts to inform policy change.

Ferrari said the risk that these shipwrecks pose is not just the slow leakage of oil that was seen from the Coimbra.

The ships could suffer a catastrophic collapse of their structures that would release large quantities of oil all at once.

That is not just a possibility but “almost an inevitability” after decades of decay, according to Ferrari.

He said the divers who inspected the Coimbra found not just a few holes but a generalised weakening of the vessel’s seams and the dilapidation of its bolts.

And impacts from heavy fishing gear had made the situation worse. The weaker a hull gets, the more of a problem those impacts become.

A major part of the Lloyd’s Register Foundation coalition-building efforts is bringing together organisations that have information about legacy wrecks that could have oil in them.

The IUCN said in April that a dearth of data, alongside a lack of international cooperation, has resulted in action coming too late to prevent serious harm from pollution from shipwrecks.

Louise Sanger, head of research, interpretation and engagement at the Heritage & Education Centre, pointed to the research of Innes McCartney, a maritime archaeologist and historian at the UK’s Bournemouth University who used digitised records made available online by the centre to identify wrecks that pose a risk.

“They’ve already been used to identify over 129 previously unidentified wrecks, and that’s just through one small study,” she said in a podcast interview.

Another key element of the effort is increasing awareness about the problem.

Ole Varmer, senior advisor on ocean heritage for The Ocean Foundation, said his organisation has a strong interest in spreading ocean literacy aligned with the United Nations’ sustainability goals, and a book on the shipwrecks challenge is due out this year.

He said some communities have experienced the impacts of pollution from shipwrecks, such as loss of animal life.

“This issue involves a threat that is not apparent to the general public,” he told Green Seas.

“We decided that this is important for us to show that potentially polluting wrecks are a threat to our ocean, both natural and cultural heritage.

“And ocean science is important in addressing that threat and making sure that we have a healthy ocean for present and future generations because the ocean is so important to quality of life.”

Another key element of the efforts to tackle the threat of oil spills from wrecks is finding solutions, including capacity building to make those solutions possible.

“The Lloyd’s Register Foundation works very much on convening coalitions for change, and that’s very much at the heart of this project,” said Sanger.

“We know that it’s a problem that’s global. We know that it’s a problem that can’t be solved by one country.

“It needs to be tackled at a global level, ultimately, and we want to convene stakeholders that can input to that, whether that’s bringing together data and evidence, whether it’s bringing together technical solutions, or whether it’s bringing together the potential financing and mechanisms that are going to be needed to achieve that.”

She said the project is gearing up for workshops that include a deep look at the technological landscape, and she noted that companies in innovation and technology in the maritime sector have shown interest in taking part.

In addition to a workshop focused on data collection, another will explore the regulatory landscape. After all, the ultimate solution will take more than a coalition of nonprofit groups.

While authorities in the US have dealt with the oil from the Coimbra and the 7,869-gt Jacob Luckenbach (built 1944), a cargo vessel that sank in 1953 and began leaking oil off California in 2001, many wrecks lie off the coast of less developed countries, which have fewer resources to respond to a spill and would suffer economic and ecological consequences.

“At least in the Asia Pacific, there are so many World War II wrecks from the US, Japan, Australia, Canada and … the UK, but they’re lying in the waters of lesser developed nations,” Varmer said.

Scuba divers are drawn to such sites, such as Chuuk Lagoon in Micronesia. Formerly known as Truk Lagoon and the home of an important Japanese naval base during World War II, the area has a multitude of wrecks that are a key tourist attraction, but the oil contained in those vessels makes them a high risk.

Varmer said the economies of many such lesser-developed nations are dependent on tourism and fishing.

“If one of these wrecks starts to have the release that has happened, for example, on the coast of California and the Luckenbach, it is going to have a severe economic impact on the livelihoods of fishermen and the coastal eco-cultural tourism,” he said.

“So that’s one of the reasons that we’re trying to get ahead of this, but the solutions really have to come from the governments that have the regulatory authority.”

Varmer, a lawyer focused on environmental and historic preservation law, said coastal states and vessels’ flag states are a key part of that puzzle. The International Maritime Organization might be the most important UN institution in this regard, although Unesco should have a key role because many wrecks are in locations that are recognised for their cultural and natural heritage, he said.

The IUCN, a Switzerland-based organisation that has consultative and observer status at the UN, has also argued that the IMO can help facilitate collaboration through its existing frameworks, noting that the UN High Seas Treaty also provides a forum for international action.

The group has argued that a “new international standard” is needed to determine best practices and a way to classify sunken vessels according to their potential impact.

“Applying the standard will help governments know how, where and when to act, and allocate global resources most effectively,” it said last April.

At the time, the IUCN said more research was needed to inform the structure of an international standard.

Adding to the puzzle, the group has also argued that it is unclear who is responsible for the cost of dealing with pollution from shipwrecks.

Climate change is adding to the urgency to tackle the problem, because of the increasing frequency and intensity of severe weather events.

“They’re speeding up the process of wrecks, and there’s evidence that’s showing that rapid deterioration, breaking apart of wrecks on the seabed,” said Sanger.

“If you think in terms of the time many of these wrecks have been down there, especially from the world wars, there’s been 75 years of corrosion already, so leaks from sunken vessels are expected to reach their highest levels within about 10 years.”

But she said there is not enough data, or even enough data scientists focused on the problem, to figure out when or where those individual leaks might occur.

A team at the National Museum of Denmark is working on the question of how long ships’ steel can last in such conditions, and it will be the subject of a chapter in the upcoming book with The Ocean Foundation.

But Sanger called for a systematic approach to identifying where the most volatile wrecks and biggest risks are and said there is a need for urgency to figure out the question of how to pay for leaks.

The project team leaders said the approach to such oil spills so far has been an “emergency response mode” that focuses on responding to leaks after they happen.

But they said that is not cost-effective.

“Investment now will save billions in avoided costs,” said Ferrari.

“We all know, however expensive it may be — and it can be costly to remediate these wrecks — that is a very small amount of money compared to what it costs to reconstruct coastal industries, coastal environments and coastal communities. Action now is the sensible thing to do.”

Read more

- Wind assist pioneers storm into the new year with dozens of ships

- Year Ahead: IMO sets the stage for decarbonisation policy

- Euronav spends half Fredriksen cash on $1.15bn buy of Saverys’ CMB.TECH green start-up

- Podcast: Turning IMO’s net-zero strategy into action in 2024

- K Line ultramax to be built with Japanese green steel